TVA’s Kingston Fossil plant is one of the many coal-burning facilities in Central Appalachia’s front yard. Yet, fewer and fewer plants in the Southeast are purchasing coal from Appalachia. Instead, utilities are looking to the cheaper Powder River and Illinois basins. Photo from tva.com

We posted a piece yesterday about the retirement plans for Brayton Point Power Station in Massachusetts – the most modern coal-fired power plant in New England – and how some are calling its eventual closure a death knell for coal in the Northeast.

Or, as Jonathan Peress of the Conservation Law Foundation said in a press statement, “if [Brayton Point] can’t make a go of it, none of them can.”

Unsurprisingly, the owners of Brayton Point, like most other utilities that are retiring plants or converting them to burn other fuels, cited the surplus of low cost natural gas and the ongoing market transformation it has caused as major factors in coal plant closures nationwide.

The fact that the nation’s natural gas boom is hastening the decline of Central Appalachian coal is no secret. But it leaves out any mention of the challenge from cheaper coal and competing reserves. In turn, inescapable aspects of the forces shaping coal’s future in the region rarely see the light.

When even southeastern utilities that operate coal plants in Central Appalachia’s front yard look to Wyoming’s Powder River Basin or the Illinois Basin, it goes beyond the price of operating an aging plant to the price of coal at the mouth of the mine. And for several years, Central Appalachian coal has been losing out.

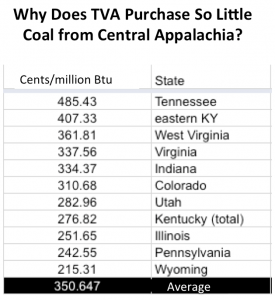

Central Appalachian coal comes at a higher price than other reserves, shown here in cents per british thermal unit, compounding the challenges presented by cheap natural gas and low demand.

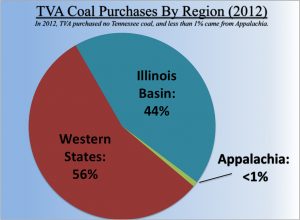

The Tennessee Valley Authority and Southern Company, both preeminent power providers in the Southeast, have stopped buying Central Appalachian coal almost entirely, even at plants that have been powered by Appalachian coal for decades. Already, less than 1 percent of TVA’s coal purchases come from Appalachia, and Southern Company expects coal purchases from the region to drop to 1 percent of its total receipts by 2016, according to Platts Energy.

In the West Virginia State Journal, Jim Ross writes that TVA and Southern Company no longer need to buy Central Appalachian coal because they can burn cheaper, and dirtier, coal from the Illinois Basin and still meet Clean Air Act requirements.

“It was the Clean Air Act amendments of 1990 that helped squeeze Illinois Basin coal out of the market in favor of [Central Appalachian] coal,” writes Ross, “but advancements in scrubber and pollution control technology are helping Illinois Basin coal regain some of its lost market share.”

As a whole, SNL Energy reports that Central Appalachian coal costs up to $20 more per ton than coal from the Illinois Basin. Robert Hardman, the director of Southern Company’s coal services, said that transitioning the utility’s coal-fired fleet almost entirely away from Central Appalachian coal will “translate into savings of hundreds of millions of dollars a year for our customers.”

“The use of Central Appalachian coal is declining because the coal industry can no longer mine Appalachian coal at a cost that is competitive with other fuels,” says JW Randolph, Appalachian Voices’ Tennessee director.

Less than 1 percent of the coal purchased by TVA comes from Appalachia. Atlanta-based Southern Company is also being pushed by the market to reduce Appalachian coal receipts.

Randolph says that TVA’s 900-megawatt Bull Run plant in Anderson County is the last remaining plant burning Central Appalachian coal in Tennessee. But just one-tenth of the coal burned at Bull Run comes from Appalachia.

“Within the next year or two, we could see the complete phase out of Central Appalachian coal at TVA plants.” he says. “The future of Central Appalachian coal in the Tennessee Valley is almost nonexistent.”

While in Tennessee for the Society of Environmental Journalists conference last week, several of us toured TVA’s Kingston plant. Historically, the plant has burned Central Appalachian coal, but now runs entirely on Powder River and Illinois basin coal.

Read more posts in this series:

“You could sit on top of Buffalo Mountain with an industrial-strength slingshot and toss the coal from the mine mouth straight into the boilers at Kingston,” Randolph says. “But despite the fact that this coal plant sits about a dozen miles from the coal-bearing areas of Central Tennessee, it would still not be economical for TVA to burn that coal. That’s how out of the picture Central Appalachian coal is right now.”

While our efforts to stop MTR in Central App have directly benefited from these cost differentials, it seems that the conversion of many CF plants to gas , and the switch to the poorer quality western -sourced coal have their environmental down sides as well. Certainly, the unknowns associated with fracking and its largely unregulated state are of great concern.

There is also an unintended consequence of the CAA control technology regs which have , in effect, prolonged the lives of many CF plants by making them capable of burning the poorer quality cheaper coal. Also, the western coals generate proportionally more waste ( ash, sulfur ) and, as they have lower BTU/lb content, more must be burned to produce equivalent electrical power. Poorer quality coal also causes operational problems with the boilers as well as with the control devices and these can result in actual increases in annual emissions due to control device failures, operational malfunctions, and increase maintenance and operational problems. Western coal usage can, thus, cause deterioration in emission control systems and thus greater air pollution.

Hopefully, our campaign to move to truly sustainable energy and increased efficiency will eventually prevail.

Really great points Rick. I wonder about the costs associated with burning that poorer quality coal that are not factored into an electric utility’s decisions. If they were factored in, would it change the decision to prolong the life of 50, 60-year-old coal plants? Maybe forgoing CAPP coal purchases will “translate into savings of hundreds of millions of dollars a year,” but the ways we put a price tag on natural resources and the value they represent are still woefully inadequate, as you touch on. In any case, it’s no surprise that Central Appalachia is getting the worst of it, busting while watching their competitors boom. So now is the so-called “war on coal” a “war on Appalachian coal,” or are decision makers in the region still blinding themselves to the urgency of the situation? Thanks again for the comment.