Cleaning Up Coal Ash

For well over a century, power plants across the country have burned coal to generate electricity. And for just as long, leftover coal ash has been dumped in open, unlined pits near the power plant, usually located on a river or lake. Every year, U.S. power plants produce 130 million tons of coal ash, which is the second largest waste stream in the country after municipal garbage.

Coal ash concentrates the toxic heavy metals found in coal, including arsenic, mercury, lead and selenium. Stored in unlined, wet impoundments, coal ash has been leaking these toxics into our groundwater and surface waters for years. Sometimes these impoundments collapse — with disastrous results.

Yet government regulations for coal ash management are either non-existent or sparse, and there is little enforcement of the regulations that do exist. In North Carolina, this lack of oversight — and the complicity between state regulators, elected officials and Duke Energy — came to a boiling point in February 2014 when one of Duke’s coal ash impoundments spilled 39 million tons of ash into the Dan River.

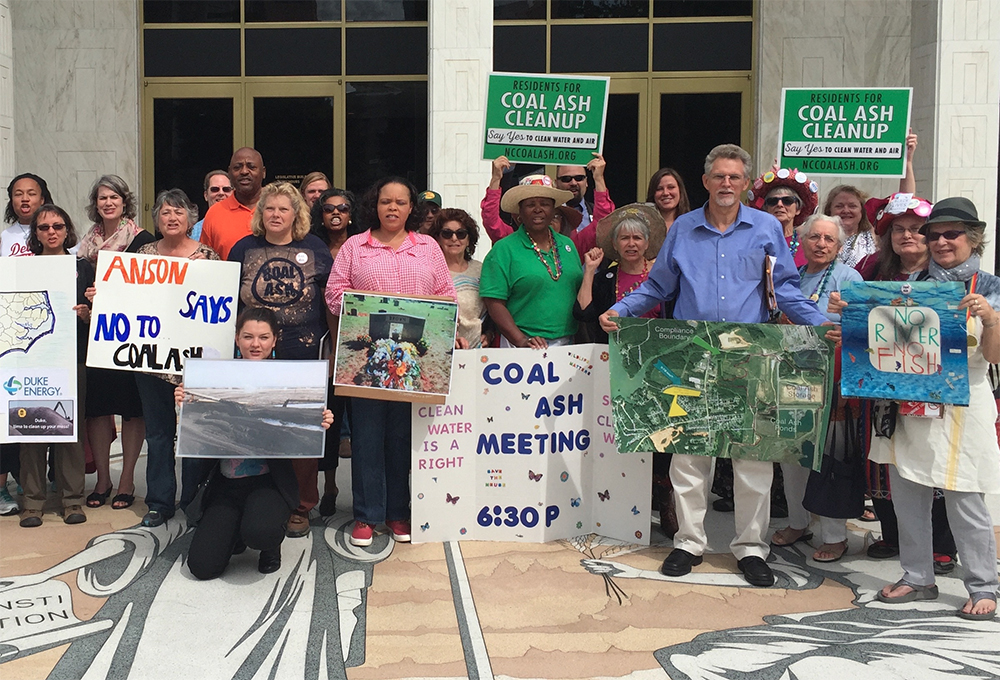

Citizens living near North Carolina’s 33 coal ash impoundments — all of which have leaked — have fought for transparency from Duke and the state, and for cleanup of the pollution that threatens their property value, health and family. Their actions forced this issue into the headlines of news networks and to the forefront of environmental justice conversations in the United States.

Appalachian Voices stood with these communities as we worked for years to compel Duke Energy and the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality to excavate coal ash from all the North Carolina sites and dispose of it either in lined, dry landfills, away from waterways, or by recycling it for concrete or other uses, provided it’s done in a manner that protects public health and the environment.

On Jan. 2, 2020, North Carolina announced a historic settlement with one of the state’s most powerful corporations and polluters, Duke Energy. The settlement requires Duke to move nearly 80 million tons of toxic coal ash at six of its power plants to properly lined landfills onsite or recycle it.

Learn information about specific coal ash impoundments in the South, including health threats and safety ratings:

Additional Resources

Fact sheets, videos, links to academic research, and more

Sign Up to Act

Help us protect the health of our communities and waterways.

Latest News

A Tennessee Homecoming

Appalachian Voices reopens its Tennessee office and is working to bring energy efficiency to the state.

Communities Coming Together To Clean Up Coal Ash

Appalachian Voices is proud to support the Alliance for Carolinians Together (A.C.T.) Against Coal Ash, a new grassroots organization representing North Carolinians impacted by coal ash.

Protecting Streams

Appalachian Voices is working with partner groups to help local communities speak out in favor of stronger regulations protecting their streams and people from mountaintop coal removal.

Clean Energy Advocates Criticize APCo Solar Proposal

Appalachian Power Company seeks to add fees to its costumers who switch to solar energy, causing many to worry that this cost may discourage some from choosing this clean energy option.

By the Numbers: Lyme Disease, Conservation Funding, Smoky Mountains and more

11 Ranking the Great Smoky Mountains National Park…