Cleaning Up Coal Ash

For well over a century, power plants across the country have burned coal to generate electricity. And for just as long, leftover coal ash has been dumped in open, unlined pits near the power plant, usually located on a river or lake. Every year, U.S. power plants produce 130 million tons of coal ash, which is the second largest waste stream in the country after municipal garbage.

Coal ash concentrates the toxic heavy metals found in coal, including arsenic, mercury, lead and selenium. Stored in unlined, wet impoundments, coal ash has been leaking these toxics into our groundwater and surface waters for years. Sometimes these impoundments collapse — with disastrous results.

Yet government regulations for coal ash management are either non-existent or sparse, and there is little enforcement of the regulations that do exist. In North Carolina, this lack of oversight — and the complicity between state regulators, elected officials and Duke Energy — came to a boiling point in February 2014 when one of Duke’s coal ash impoundments spilled 39 million tons of ash into the Dan River.

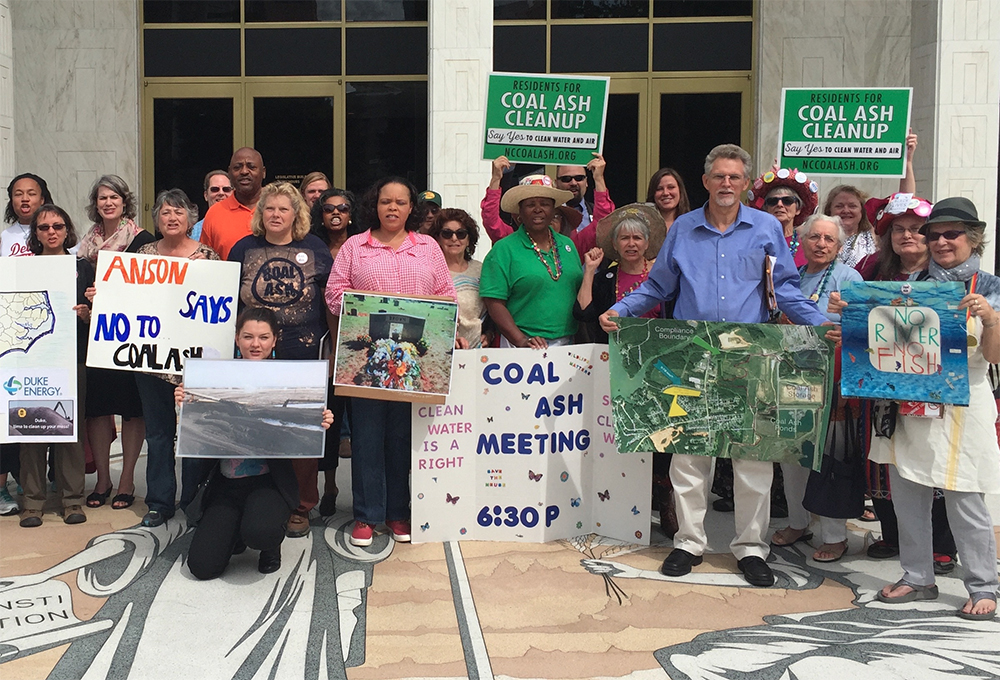

Citizens living near North Carolina’s 33 coal ash impoundments — all of which have leaked — have fought for transparency from Duke and the state, and for cleanup of the pollution that threatens their property value, health and family. Their actions forced this issue into the headlines of news networks and to the forefront of environmental justice conversations in the United States.

Appalachian Voices stood with these communities as we worked for years to compel Duke Energy and the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality to excavate coal ash from all the North Carolina sites and dispose of it either in lined, dry landfills, away from waterways, or by recycling it for concrete or other uses, provided it’s done in a manner that protects public health and the environment.

On Jan. 2, 2020, North Carolina announced a historic settlement with one of the state’s most powerful corporations and polluters, Duke Energy. The settlement requires Duke to move nearly 80 million tons of toxic coal ash at six of its power plants to properly lined landfills onsite or recycle it.

Learn information about specific coal ash impoundments in the South, including health threats and safety ratings:

Additional Resources

Fact sheets, videos, links to academic research, and more

Sign Up to Act

Help us protect the health of our communities and waterways.

Latest News

Public informational meeting to be held on July 23 to discuss Transco Pipeline Expansion project

A 54-mile methane gas pipeline and compressor stations are planned to cut through parts of North Carolina and Virginia in a project called the Southeast Supply Enhancement Project, also known as the Transco Pipeline Expansion.

House committee advances reckless bill that blocks life-saving silica standard

Today, the House Appropriations Committee approved a dangerous appropriations bill for the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education. Among other disastrous provisions, the bill would block funding for the recently finalized rule to protect miners from silica dust

Communities identify priorities during first listening sessions of multi-year project

In late April, Appalachian Voices started our first round of Community Strong listening sessions, part of a multi-year project to plan, design and implement community-driven projects.

Pound receives grant for monument to region’s labor history

The town of Pound has recently received a $217,000 grant from Virginia Tech’s Monuments Across Appalachian Virginia program to construct a monument paying tribute to the region’s labor history.

Paddling for her Life

Farmer Ann Rose is paddling nearly 2,000 miles solo to bring attention to water woes in Appalachia.

New law protects Virginians against utility shut-offs during extreme heat

As heat waves roll through Virginia, a new law to protect residents from unsafe utility shut-offs during periods of extreme weather goes into effect on July 1.