Cleaning Up Coal Ash

For well over a century, power plants across the country have burned coal to generate electricity. And for just as long, leftover coal ash has been dumped in open, unlined pits near the power plant, usually located on a river or lake. Every year, U.S. power plants produce 130 million tons of coal ash, which is the second largest waste stream in the country after municipal garbage.

Coal ash concentrates the toxic heavy metals found in coal, including arsenic, mercury, lead and selenium. Stored in unlined, wet impoundments, coal ash has been leaking these toxics into our groundwater and surface waters for years. Sometimes these impoundments collapse — with disastrous results.

Yet government regulations for coal ash management are either non-existent or sparse, and there is little enforcement of the regulations that do exist. In North Carolina, this lack of oversight — and the complicity between state regulators, elected officials and Duke Energy — came to a boiling point in February 2014 when one of Duke’s coal ash impoundments spilled 39 million tons of ash into the Dan River.

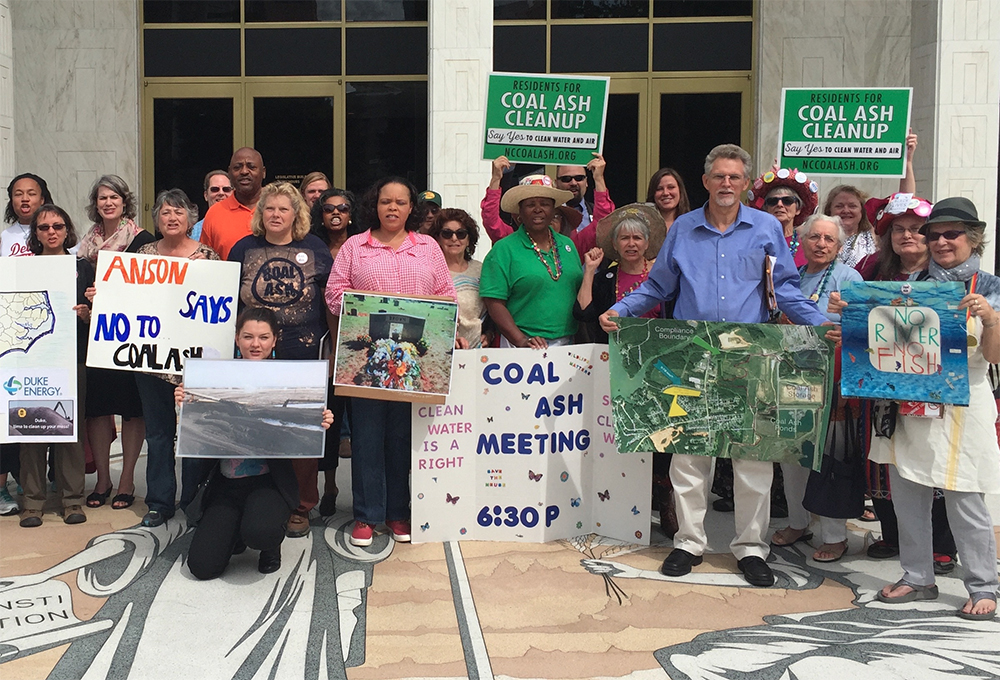

Citizens living near North Carolina’s 33 coal ash impoundments — all of which have leaked — have fought for transparency from Duke and the state, and for cleanup of the pollution that threatens their property value, health and family. Their actions forced this issue into the headlines of news networks and to the forefront of environmental justice conversations in the United States.

Appalachian Voices stood with these communities as we worked for years to compel Duke Energy and the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality to excavate coal ash from all the North Carolina sites and dispose of it either in lined, dry landfills, away from waterways, or by recycling it for concrete or other uses, provided it’s done in a manner that protects public health and the environment.

On Jan. 2, 2020, North Carolina announced a historic settlement with one of the state’s most powerful corporations and polluters, Duke Energy. The settlement requires Duke to move nearly 80 million tons of toxic coal ash at six of its power plants to properly lined landfills onsite or recycle it.

Learn information about specific coal ash impoundments in the South, including health threats and safety ratings:

Additional Resources

Fact sheets, videos, links to academic research, and more

Sign Up to Act

Help us protect the health of our communities and waterways.

Latest News

Appalachia’s Environmental Votetracker: Aug./Sept. 2014 issue

See how Appalachia’s congressional delegation voted on environmental issues.

Leaving coal ash in place is not a cleanup plan

Appalachian Voices • Greenpeace • NC Conservation Network…

Environmental community calls for major changes to North Carolina House’s coal ash bill

Environmental community calls for major changes to North Carolina House’s coal ash bill

Community Impacts of Controversial Coalfields Expressway Project in Va. to Receive Thorough Review

Agency letters Federal Highway Administration, May 22, 2014…

Groups Seek Protection of Virginia Waterways from Mining Pollution

Red River Coal Co. Violating “Last Line of…

At What Cost?

Concerns about Duke’s toxic coal ash have prompted Annie Brown and dozens of other community members to meet regularly since July 2013 to discuss how to get it out of their neighborhood once and for all. The group, which calls itself “Residents for Coal Ash Cleanup,” has recently grown in size, becoming more outspoken and more certain of their demands.