Democratizing the Grid

The Opportunities and Obstacles of Community-owned Renewable Energy

By Brian Sewell

When energy experts talk about distributed generation, they describe it as both a threat that will disrupt markets and erode utility profits and an opportunity that is changing the way electricity is generated, transmitted and delivered. Or as the chairman of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Jon Wellinghoff, said last year, “The traditional utility is either going to have to change or die.”

Unlike power generated by a coal plant, nuclear station or other centralized power sources, distributed projects are owned by individuals, communities or small businesses. As the electric grid becomes more widely distributed, it becomes more stable and efficient, and relies increasingly on cleaner energy from rooftop solar panels and, in the right locations, community-scale wind farms.

With easier ways for individuals and communities to own renewable projects, greater access to technologies, and falling prices, more consumers are producing their own electricity and slowly turning the electric utility business model upside down.

The Distributed Present

In states such as California, Arizona and Colorado — all leaders in residential and small-scale renewable energy — solar leasing and power purchase agreements between clean energy producers and buyers of electricity have helped expand capacity for homeowners and businesses to create and sell energy.

According to the Solar Energy Industries Association, third-party-owned systems accounted for more than half of all new residential installations in 2012, evidence that the market for distributed solar is attracting savvy investors. And with the emergence of crowdfunding and online solar marketplaces where you can shop for equipment and search for installers, supporting renewable energy is easier than ever.

In areas where third-party ownership options are limited and policies favor utilities, community-ownership models are providing an alternative path to clean energy. In North Carolina, the Boone-based Appalachian Institute for Renewable Energy is helping communities, campuses and congregations afford rooftop solar installations.

In 2011, The Appalachian Voice first reported on a 10-kilowatt rooftop solar project facilitated by AIRE and installed by Sundance Power Systems on the First Congregational United Church of Christ in Asheville, N.C. Since then, the group has helped other congregations and the Town of Carrboro develop community funded and owned rooftop solar systems.

- Raising the Standard: State Laws and our Clean Energy Future

- Democratizing the Grid: Community-owned Renewable Energy

- Bio-energy Creates a Mass of Questions

- Beyond Renewable: The Cutting Edge in Energy

- A Guide to Clean Energy Incentives

Since its inception, AIRE has pioneered a community-ownership model that helps investors to receive tax benefits and rebates for renewable energy development. In certain situations, these incentives can pay for more than 80 percent of a solar system’s cost, but they are often only available to larger businesses and wealthy individuals.

In the years after installing a project, donors and investors realize the tax benefits and earn income from the sale of energy and renewable energy credits. And the investors that own the system can either donate or sell it to a nonprofit or community group for a fraction of its original cost.

Projects facilitated by AIRE in North Carolina are grid-connected, so the sites do not actually use the electricity they produce. Instead, the project owners sell electricity to utilities like Duke Energy, which developed a solar program in response to North Carolina’s renewable energy standard.

Throughout Appalachia and the Southeast, groups like AIRE are creating opportunities for communities, and industry leaders such as SolarCity, Sungevity and Mosaic are focusing on solar-friendly policies to facilitate renewable projects in as many states as possible.

Beyond directly investing in distributed generation, some electric membership cooperatives are making it a priority to provide their communities access to cleanly produced energy. In Georgia, Green Power EMC has partnered with 38 membership cooperatives statewide and produces energy from a landfill gas-to-electricity facility, a low-impact hydro facility, and a wood waste biomass plant.

Even the U.S. Department of Energy recognizes the potential for community-owned renewable energy, and has developed a Community Renewable Energy Deployment tool to help groups get their own projects off the ground.

Distributed technologies and community-owned projects can bring about a brighter energy future. But there are still challenges preventing the widespread adoption and affordability of renewables.

Challenges to Community Ownership

While large solar projects still account for the majority of the nation’s rising renewable capacity, nearly 83,000 homes installed solar panels in 2012 totaling 488 megawatts of capacity — more than the utility and commercial markets did in 2009, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association.

But the spectrum of policies that encourage the expansion of this distributed generation vary widely from state to state.

Power purchase agreements, which have become effective tools in California and Arizona, are prevented in Georgia, Kentucky and North Carolina, and laws remain unclear in the remaining central and southern Appalachian states.

In addition, all Appalachian states impose limits on how much excess energy generated from distributed sources can feed the grid and be credited on the owner’s next utility bill, a process called net metering. As a result, owners of renewable projects have little incentive to produce more energy than they need.

Improving methods for storing and transmitting electricity would bolster grid reliability and enable the increased use of power generated from renewables. Unfortunately, today’s grid has virtually no storage.

U.S. Department of Energy researchers are investigating new energy storage technologies, including sodium and lithium ion batteries, flywheels and electrochemical capacitors, that could be deployed at any location in the country.

Eventually, these new technologies could turn a home or business into a mini-utility, managing a more effective means of power generation and delivery, while the grid supply serves as a back-up.

But even more than technological barriers, which are frequently broken, wealthy and politically powerful utilities could resist competition from distributed resources by pushing governments and regulatory commissions to adopt restrictive policies that discourage renewable growth and preserve profits.

A Perpetual Threat

In recent years, Duke Energy CEO Jim Rogers has been upfront about the threat of distributed generation to the traditional way of producing electricity.

Rogers has expressed fear that distributed generation will remove utilities like Duke from the relationship between consumers and their power sources, a process known as disintermediation. “What [disintermediation] really means is a Google comes in with an idea about improving the energy use in the home and the next thing you know the demand drops 30 percent,” Rogers said to a group of energy investors and regulators at the Deloitte Energy Conference in 2011.

Even industry leaders are beginning to subvert the centralized model. NRG Energy, the largest wholesale electricity provider to power companies in the United States, is beginning to undercut the interests of some of its largest clients by installing solar panels on rooftops of homes and businesses. The CEO of NRG Energy, David Crane, recently predicted that the natural gas industry has the potential to remove the utility from the equation if customers that require large amounts of electricity like Walmart or a computer data center install natural gas generators.

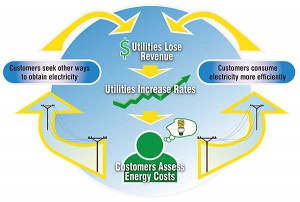

Crane and others anticipate that, as more consumers and businesses generate more of their own electricity, those who are not able to install or invest in distributed generation will increasingly bear the costs of maintaining the grid and more centralized sources like power plants. But as a January 2013 report by Edison Electric Institute points out, as rates rise on consumers, community-owned energy will only become more attractive to investors and a utility’s ratepayers.

Even though rooftop solar’s share of electricity is low — rooftop solar currently accounts for less than one percent of the total electricity generated in the United States — distributed resources represent a perpetual threat to utilities, at least to those unwilling to adapt.

In the meantime, Duke and others are motivated to take steps toward the distribution edge — where customers, power providers and distributed energy resources meet. In June, the utility became an investor in Clean Power Finance, a residential solar financing company that manages half a billion dollars for third-party investors in distributed solar projects.

Regardless of the scale or speed, greater education and supportive policies have already created consumer participation and a movement to democratize the grid. But will utilities use their power to lead or find that they have been forced to follow?

Financing Community-owned Renewable Energy

The Donor Model:

In this model, individual donations allow nonprofits or community groups to own the system outright and benefit from the electricity generated. In North Carolina, donors receive a 35 percent state tax credit and a tax deduction on their federal return for a charitable donation.

The AIRE Model, Create an LLC:

In the model pioneered by AIRE, investors own the system and benefit from the tax credits, depreciation, and revenue from selling the electricity and Renewable Energy Credits. After a period of six or seven years, depending on price of electricity and other elements of the marketplace, the investors can donate or sell the system.

Third-party Payer Power Purchase Agreement:

Investors install an array and make an arrangement with the church to sell electricity at a specified rate. Investors benefit from the depreciation, tax incentives and sale of electricity. This model cannot used for solar electric in North Carolina, but First Light Solar in Asheville developed a similar Solar Energy Purchase Agreement model for hot water, since the sale of heat is not regulated by the state utilities commission the same way as electricity.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment