Front Porch Blog

Empty coal train cars sit near the Carbo Power Station, in Russell County, Va. Carbo is one of many formerly coal-fired power stations that has switched its boilers to natural gas. Photo by Matt Hepler

Coal production in Central Appalachia has been steadily declining for the past two decades. Over the past few years, this trend has been exacerbated by numerous bankruptcies, and strained even further by COVID-19. Recently released data from the Mine Safety and Health Administration, aggregated by Open Source Coal, show just how bad things have gotten both nationally and within Central Appalachia for the mining industry. It is difficult to separate out how much of this decline is due to COVID and how much is just the continuation of longstanding market trends, but comparisons between 2020 Quarter 1 and 2020 Quarter 2 show a particularly dramatic drop in production.

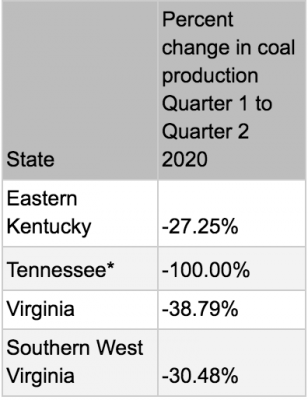

Numerous mines temporarily idled operations during the start of the pandemic, resulting in lower coal production during that time period. Since last quarter, coal production dropped approximately 25% nationally, while Central Appalachian production dropped 33%. The drop in production of the Central Appalachian states is shown below. Many counties also saw significant declines in production in the second quarter, while a small number of counties saw increases in coal production despite COVID-19, mostly due to increases in production on existing mines in those counties.

Tennessee coal production fell to zero in the second quarter of 2020, though it is unclear if this is due to an error of reporting. The mines from the previous quarter were both owned by Kopper Glo, which had idled their operations earlier this year.

Making a bad situation worse

Coal’s decline presents several major hurdles for the region — from eroding local tax bases, to jeopardizing federal programs for mine cleanup and miners’ health programs, and the potential for a new wave of widespread mine abandonment.

The cleanup of Abandoned Mined Lands (AML) is one area that will feel the impact of declining coal revenues. A fee on coal production, collected by the federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement and distributed to state and tribal governments, funds the remediation of environmental and public safety hazards caused by mining prior to the passage of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act in 1977. Currently the AML fee is set at 28 cents per ton on surface-mined coal, 12 cents per ton on coal mined underground, and 8 cents on lignite coal production. The amount of estimated AML cleanup costs is greater than $13 billion and greatly exceeds the current funds available to clean up AML features. Even if a bill passes next year to reauthorize the collection of the AML fee, it is unlikely given coal’s current decline that the money generated will be enough to clean up the remaining abandoned mine land features.

ArcGIS Online Map of County Coal Production: Data originates from Open Source Coal and MSHA; some counties that produced coal in the past but not in the past two quarters may not be reflected on this map. Some data on the mine production layer may be geographically inaccurate due to bad location data stored within the MSHA database. Map by Matt Hepler

Similarly, the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund relies on an excise tax of $1.10 on every ton of underground coal production, and 55 cents per ton of surface mined coal. This black lung fund pays for disability benefits and medical care for miners suffering from black lung disease whose employers have gone bankrupt, a situation that is becoming increasingly common.

Currently the excise tax rate is scheduled to be cut in half at the end of 2020 unless Congress acts. The Black Lung Association campaigned hard and won a one-year extension of the tax in 2019, and is now pressing Congress to extend the tax at its current rate for 10 years. But even if this crucial funding source for the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund is secured, the tax revenue collected will continue to diminish along with coal production. Meanwhile miners’ lungs face the dual threats of a growing black lung epidemic and the coronavirus.

The declining coal production will also be particularly impactful on small towns trying to reckon with unbalanced budgets. Even before the pandemic, local governments in Central Appalachia were experiencing the stress of declining coal severance tax revenue. Such severance taxes have been used to build and maintain water systems, secure public workers’ pensions and fund various other government services. One judge-executive in Kentucky told the Lexington Herald-Leader that COVID was “the second pandemic,” citing years of declining coal economy as the first.

The pandemic’s impacts

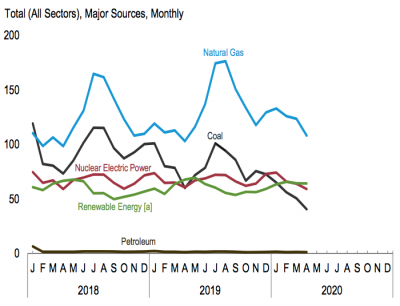

The pandemic is also having a broader impact on the coal industry. According to a recent report by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, national coal-fired electricity generation hit a 42-year low in 2019, and as of May 2020 had fallen another 34%. As of April, national electricity usage had fallen 4% from the previous year. And though residential use had increased 8% during that period, the overall demand was offset and then some by less energy used in the commercial and industrial use.

Similarly, January through May of 2020 saw a 29% decrease in coal exports from the previous year. Due to both declining exports and declining electricity generation, the U.S. Energy Information Administration is forecasting a 29% decline in coal production through 2020, with some degree of rebound expected in 2021.

Renewable energy and coal’s decline

One of the brighter spots in the data from the past few months is that renewable energy has surpassed coal in national electricity production (the EIA includes hydroelectricity in the definition of renewable energy in that figure). While this change was likely to happen anyway, the pandemic has accelerated that transition. In the month of May, electric generation from renewables without hydro was about 94% of coal-fired generation, making it seem like renewables without the use of hydro will surpass coal very soon.

Electricity generation by source: Graph and content from EIA July 2020 Monthly Energy report pg 128

Coal production has been moving downward for decades now, but the pressure on the industry has been particularly intense the past few years. There was already a growing list of coal bankruptcies prior to the pandemic, with the Rhino bankruptcy being the latest. COVID-19 is accelerating that decline, and while some of its impacts are probably temporary, it is likely that much of the decline will be permanent. This will leave already-shortchanged coalfield communities even less money to deal with decades of damage to people’s health and the environment.

This underscores the importance of making sure the bad actors behind the region’s negligent coal companies, like former Blackjewel CEO Jeff Hoops, are held accountable for fixing their share of the problems that they created. It is clearer than ever that communities in Central Appalachia can no longer count on a coal-based economy to help pay for their share of AML cleanup or supply the tax revenue to support local schools. Despite promises from some national and regional politicians that coal will return, the need for a new path forward is clear. And local, regional and even national networks of coal-impacted communities are putting forward their plans for the future. Coal is declining, but the industry doesn’t have to take the region down with it.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *