Communities ACT

Walnut Cove … Belmont … Goldsboro — in communities around North Carolina, citizens over the years have had to put up with soot, noise and truck traffic coming from a coal-fired power plant operating in their midst. Some also noticed an unusually high incidence of cancer.

In February 2014, the now-infamous Dan River coal ash spill revealed a slow-brewing crisis — potentially contaminated drinking water due to leaking coal ash pits at Duke Energy’s power plants all across the state.

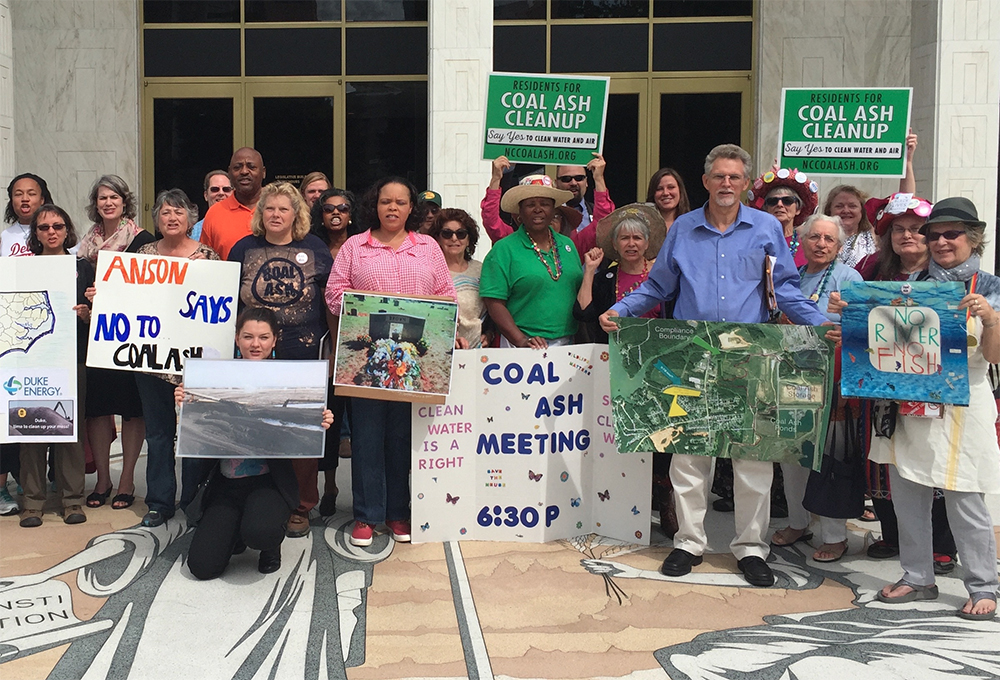

In the aftermath of the spill, as state officials and Duke executives did little but lay blame and spin messages to protect their own reputations, citizen groups and communities banded together to fight back.

The Alliance of Carolinians Together (ACT) Against Coal Ash formed in 2015 with support from Appalachian Voices. The alliance issued a set of unifying principles calling on then-Governor Pat McCrory, state lawmakers and Duke to ensure no community is left to suffer from coal ash pollution and to demand transparency in all decision-making around the coal ash crisis.

“We are in a fight for our lives.”

In 2015, well water samples of people living near coal ash showed elevated levels of coal-related contaminants such as arsenic, chromium and vanadium, and the health department warned more than 400 households not to use tap water for drinking, bathing or cooking. Without acknowledging any responsibility, Duke agreed to provide the citizens with bottled water — one gallon per person per day — but refused to provide filters or public water lines to the homes.

The next year, more than 1,500 North Carolinians turned out to public hearings to demand the state excavate all coal ash sites, not simply leave the ash in place with a cap, as the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality proposed at most sites.

Tracey Edwards, resident of Stokes County, N.C., holds a photo of her mother Annie Brown, who died in November 2014.

“A lot of people are afraid to speak up because they are afraid of retaliation from Duke, but I have nothing left to lose,” said Tracey Edwards, a life-long resident of Stokes County, at a hearing for the Belews Creek plant attended by more than 150 people. “We are in a fight for our lives. Our water is important to us. We need it for survival.”

As the hearings were being held, the state abruptly lifted the “do not drink” warnings with little explanation. When ACT Against Coal Ash demanded answers, the McCrory administration cast blame on career civil servants, leading to resignations and deepening the public’s distrust.

A matter of civil rights

The efforts of ACT Against Coal Ash, with support from Appalachian Voices and others, helped bring the citizens’ plight to the attention of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, which was looking into environmental justice issues related to siting and monitoring coal ash sites.

Three commission members came to North Carolina and visited the Walnut Cove community near Duke’s Belews Creek Steam Station, which has the largest coal ash impoundment in the state. Hundreds of people turned out for the commission’s public hearing, including Tracey Edwards and David Hairston, another lifelong resident of Walnut Cove. Both spoke of growing up with coal ash falling like snow and witnessing the alarming rates of illness, especially cancer, and subsequent deaths in their small, rural community.

“Duke Energy promotes poison for profit at the expense of human life,” said Edwards. “You can’t drive in any direction from the coal power plant without knowing someone who has cancer.”

“You won’t understand until you’ve lived what we’ve lived and lost what we’ve lost,” Hairston explained. “My only mother is dead, Tracey’s only mother is dead. Who else we gonna lose over the next ten years?”

In a September 2016 national report, the commission found that the percentage of minorities and low-income individuals living near coal ash sites is disproportionately high when compared to the national average. Among other things, the commission recommended that coal ash be considered a “special waste” with federal funding provided for research on the health impacts of exposure.

Still standing, still strong

ACT Against Coal Ash is holding the line of accountability on Duke and state leaders. In early 2017, when Duke offered a “goodwill” cash payment to citizens near its coal ash sites in exchange for a promise to never sue the company for potential groundwater pollution, most citizens recognized this as a back-handed offer to silence their concerns.

“A goodwill offer doesn’t come with strings attached; this is a contract, a contract to silence residents,” said Debbie Baker of Belmont, near the G.G. Allen power plant. “Duke is trying to keep people from challenging them before they even put clean water lines in place.”

“I still have young children living in the home, why would I jeopardize future generations by signing away my rights to challenge Duke on future groundwater contamination concerns?” said Amy Brown of Belmont. “Duke Energy is trying to place a $5,000 price tag on my past, present, and future groundwater contamination concerns. This is an attempt to limit our ability to protect our families.”

Appalachian Voices continues to support the alliance and partner with a variety of other stakeholder groups around the state to push for full and safe cleanup of all Duke’s coal ash sites.