Communities Aim to Solve the Opioid Epidemic

By Kevin Ridder

Heroin Hearse, a nonprofit community action group in Huntington, W.Va., drives this hearse to spread awareness of the opioid epidemic. One of their recent initiatives was to clean out a walking tunnel littered with used needles. Photo courtesy of Dwayne Woods/Heroin Hearse

Huntington, W.Va., a city located in Cabell County, has experienced a disturbing trend in the past few years. In 2015, Cabell County 911 received 944 total calls related to drug overdoses, compared to 272 calls in 2014. And in 2016, they received 1,476 calls — a 443 percent increase from 2014. The increase, according to the City of Huntington’s Mayor’s Office of Drug Control Policy, is due to the opioid epidemic.

People are overdosing on opioids — prescription drugs like oxycodone and illicit drugs like heroin — in cars, gas stations, libraries, homes, department stores and fast food restaurants in higher numbers than ever before. As Cabell County and other communities like Greensboro, N.C., attempt to adapt to an ever-worsening situation, they’re learning that traditional ways of dealing with drug addiction are not effective.

“If you arrest somebody and put them in jail, you are not really dealing with the dependency,” Capt. Rich Culler, head of the vice/narcotics division in the Greensboro, N.C., police department, says. “You just can’t arrest your way out of the problem.”

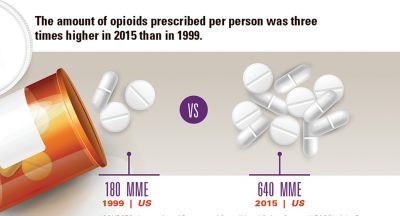

The opioid crisis in America has gotten progressively worse in recent years. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sales of prescription opioids in the United States “nearly quadrupled from 1999 to 2014,” while the amount of pain Americans reported showed no significant change. The CDC also reports that “heroin-related deaths more than tripled between 2010 and 2015,” with deaths related to synthetic opioids like fentanyl seeing a 173 percent increase from 2014 to 2015.

And Appalachia has seen the worst of it. According to Heroin.net, a resource that provides information to people suffering from drug addiction and connects them to treatment centers nationwide, Kentucky and West Virginia have been hit particularly hard. In Clay County, Ky., the average annual rate of opioid-related deaths per 100,000 residents from 1999-2013 was 115.1, compared to the national average of 5.6 deaths. In McDowell County, W.Va., the average death rate was 100.5 per 100,000 residents each year.

According to Kim Miller, the director of corporate development with Prestera Center, the largest behavioral services provider in West Virginia, much of Appalachia’s drug problem stems from pharmaceutical companies flooding the market with opioids in a region where injury-prone heavy industries like coal and timber were king.

She says that pharmaceutical companies saturated the state with drug salesmen who would tell doctors that oxycodone was effective for mild to moderate pain and wasn’t habit forming. When a coal miner was injured at work, Miller says, they would be prescribed opioids — that should be reserved for end-of-life events — to deal with pain that likely could have been managed with ibuprofen. Now, with heavy industries in decline, many former workers are left addicted to opioids and without a job. The loss of income and health insurance has turned some to the cheaper, more potent heroin.

Heroin Hearse led a cleanup of a walking tunnel littered with used needles. Photo courtesy of Dwayne Woods/Heroin Hearse

Communities are beginning to fight back against the companies that heavily marketed opioids. In northeast Tennessee, state prosecutors are filing a lawsuit targeting several large pharmaceutical companies that manufacture these drugs. According to a June article in the Knoxville News Sentinel, “the lawsuit seeks to hold Big Pharma responsible for the opioid epidemic in Tennessee by labeling the drugmakers as drug dealers and accusing them of lying about the addictive properties of opiates and aggressively pushing the drugs as miracle cures for all manner of pain.”

Culler and his department think that prescriptions should be seen as a key part of the problem.

“Instead of just arresting people, we’re going to try and get to the root of the problem, and that’s where the prescriptions come in,” Culler says. “Prescriptions, for us, were one of the ways we saw people getting addicted. Once people’s prescriptions ran out, they couldn’t get the pill anymore, so they went to buying pills on the street. But the pills on the street are more expensive, and heroin is cheaper.”

Once prescription pills open the gateway to heroin, Culler says, that’s where the overdoses happen. When someone takes a prescription opioid, it’s engineered to be a consistent dose — whereas heroin is often cut with substances like fentanyl, a cheaper and extremely potent synthetic opioid originally created by pharmaceutical companies that can kill in minuscule amounts.

In Culler’s eyes, the opioid epidemic is a simple case of supply and demand. He says that for decades, police agencies have always just tried to deal with the suppliers, no matter how low-level. But that did nothing for the demand. Since money is involved, Culler says, there is always going to be someone stepping in to fill the shoes of every supplier arrested. It’s necessary to address the demand in order to get rid of the supply.

“We want to protect people,” Culler says. “And when you see this many people dying, and you’re not having any effect, you’ve got to stop and look at what you’re doing.”

Opioid prescription rates vary greatly from county to county, according to the CDC. Graphic by CDC Vital Signs. Sources: ARCOS of Drug Enforcement Administration; 1999. Quintiles IMS Transactional Data Warehouse; 2015.

Difficulty with Treatment

Both hurting and helping the addiction epidemic are drugs like buprenorphine — commonly sold under the brand name Suboxone — used to help wean people off of opioids.

Kim Miller with Prestera Center says that medication-assisted treatment is the gold standard for treating opioid dependence, as long as it’s strictly monitored and accompanied by counseling.

“It curbs the cravings, it helps people stabilize their life,” Miller says. “Ultimately, our goal is to help people get off of buprenorphine as well. And sometimes you have to do that very slowly because people have developed psychological dependence as well as a physiological dependence on buprenorphine.”

But according to an August 2016 article in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, “[Suboxone is] the most-abused, most-sought-after street drug across [Southwest Virginia], which has been flooded with the drug like nowhere else in the state. Federal funding for drug courts requires localities to offer Suboxone in their treatment programs. Some judges have said they’d rather do without the funding — or even close their courts — rather than agree to using Suboxone.”

In a 2015 article in Alcoholism & Drug Abuse Weekly, National Association of Drug Court Professionals CEO West Huddleston said, “The real issues are, who gets [medication-assisted treatment]? What medication is appropriate for which person? How long is the appropriate course of [medication-assisted treatment]? And what is the medical rationale for making those and other decisions?”

To help curb buprenorphine abuse, Prestera Center helped West Virginia develop stricter standards for treatment, such as only giving a week’s supply of the drug at a time instead of a month’s. Additionally, patients at Prestera Center clinics must pass drug tests and attend regular therapy sessions to continue receiving buprenorphine.

In March of this year, the Virginia Board of Medication also began requiring that prescribers refer patients to counseling while undergoing medication-assisted treatment and that prescribers give only a week’s supply of the drug at a time.

From the Brink of Death

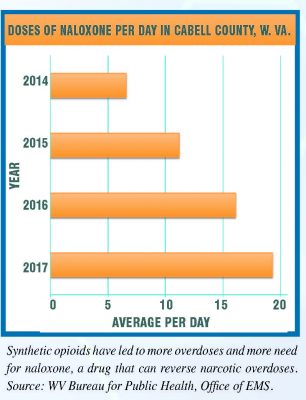

It’s become increasingly more common for first responders in all communities to carry naloxone — a lifesaving opioid overdose reversal drug that revives a victim within 60 seconds — to every call they answer.

And for good reason, says Kenny Burner, West Virginia state coordinator for Appalachia High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, a federally-funded initiative to address drug addiction and trafficking in the region. In his city of Huntington, W.Va., located in Cabell County, the fire department responds to more overdose calls than they do fires.

“You don’t have 12 fires a day, but it wouldn’t be uncommon for there to be 10 or 12 overdoses a day,” says Burner.

But even though it saves lives, Burner says that naloxone is still an extremely controversial drug in Huntington. He often hears first responders ask how many times they are going to save these people — to which he responds, as many times as needed.

“I’m not going to be the one who decides who lives and dies,” says Burner. “And that’s a personal, faith-based decision on my part. I don’t feel that anybody has the right to say no. That’s like saying we’re not going to save somebody with lung cancer because they should have known better than to smoke.”

Part of this frustration stems from what Burner calls “compassion fatigue” in first responders, who often respond to the same address over and over. Burner likens compassion fatigue to post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I think we really need to be aware of our first responders who are going out on these [overdose calls] reviving people and saving lives,” says Burner. “They’re getting tired. It’s getting worse, and I don’t think it’s peaked yet. It’s not a simple problem, and there’s not going to be a simple solution.”

Roughly 30 Huntington citizens volunteered with Heroin Hearse in July to clean up their community. Photo courtesy of Dwayne Woods/Heroin Hearse.

According to Alex Smith, an economics student at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and co-founder of the campus’ drug addiction recovery program, revival from naloxone causes side effects that do not make this frustration any easier. Naloxone can put a person addicted to narcotics in immediate withdrawal, causing extreme distress and sometimes aggression. This causes the victim to be resistant to treatment advice given at the scene.

Mat Sandifer, director of clinical services at Triad Behavioral Resources, an outpatient addiction treatment clinic in Greensboro, says Guilford County is in the process of adopting a rapid response strategy to address this in lieu of prosecuting the patient.

Essentially, the strategy entails sending a police officer, an emergency medical technician and a social worker to the victim’s home within 36 to 48 hours after the incident to talk about treatment options. Sandifer says this can include things like harm prevention, clean needle exchange, HIV and Hepatitis C prevention, inpatient treatment and outpatient medication-assisted treatment options.

The rapid response strategy, Smith says, shows promise in other communities such as Colerain Township, a suburb of Cincinnati, Ohio, with a population of 58,499.

“In the past two years since they’ve been operating [a rapid response team], they’ve had 80 to 85 percent of people they’ve engaged with say yes, they want to go to treatment or engage in some type of support services offered in that community,” says Smith. “Which is huge — you’re looking at a much smaller success rate of the people who go to the traditional 30-day treatment program.”

But as the recovery community continues to work for solutions to addiction, Smith says, Attorney General Jeff Sessions pushed the country backward when he announced an initiative in May to pursue harsher sentences for drug users.

“This is a bigger conversation,” says Smith. “Right now, we’re talking about opiates — heroin and pain pills. In the ‘80s, we were talking about crack-cocaine. This problem is going to morph into some other drug and some other epidemic if we don’t start treating it as addiction, as a health problem.”

Changing the Stigma

“I’m 66 years old,” says Kenny Burner. “When I grew up, a heroin addict was somebody in an alley in New York with a spike sticking out of their arm. Now, it’s kids my kids went to school with. It doesn’t discriminate.”

“There’s a stigma to being a ‘drug addict,’” he continues. “But they feel the worst about it. You’re looking at somebody who’s living in hell on Earth. I don’t think anybody ever wakes up in the morning and says, ‘You know, I think I want to become a heroin addict.’ That’s not the way it happens.”

According to Mat Sandifer with Triad Behavioral Resources, drug addiction is a brain disorder where the user gets completely sublimated by the drug, making the need to use more powerful than even the need to eat and sleep. He says that talking about drug addiction like a brain disorder is a crucial step in addressing the opioid crisis.

A syringe exchange kit provided by the Cabell-Huntington Health Dept. Photo by Alligator Jackson/ Alligator Jackson’s Inside Huntington WV

UNC Greensboro’s Alex Smith has a closer relationship with the negative stigma surrounding drug addiction than most. When he entered college straight out of high school 12 years ago, he was physically and mentally addicted to prescription opioids. When prescription pills became too expensive, Smith dropped out of college and started using heroin.

“[The stigma associated with drug abuse] was a big part of me not reaching out for help when I was 18,” says Smith. “There was a lot of shame and guilt that I carried along with that.”

When Smith’s family found out about his addiction, he underwent rehab and was determined to return to school. What he discovered when he returned to UNC Greensboro was a different culture regarding drug abuse on campus, one that viewed it more as a health problem instead of a moral failing.

Emboldened and wanting to reach out to a population he knew existed, Smith helped start the Spartan Recovery Program in 2014, which he says is now a familiar group on campus. He’s set to graduate next year with a degree in economics and plans to pursue a master’s degree afterwards.

“We have people who are in recovery who are doing great things,” says Smith. “That’s the wonderful thing, we’re a very resilient community. And when given the proper resources to manage our substance abuse disorder, we give back to the community tenfold.”

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *