Dr. Fred Hebard: Resurrecting the American Chestnut

By Kimber Ray

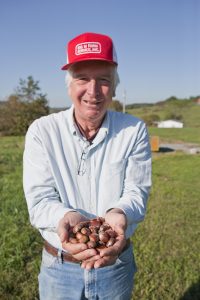

When flowers of the formerly abundant American chestnut tree adorned the Smoky Mountains, renowned 19th- century naturalist Henry David Thoreau described the scene as “covered in snow.” Here, Dr. Fred Hebard holds a handful of potentially blight-resistant chestnut seeds. Photo courtesy of The American Chestnut Foundation.

More than one hundred years ago, benevolent giants flourished in North America’s eastern forests from Maine to Mississippi, reaching up to ten stories tall and broader than the widest embrace. By the time Dr. Fred Hebard was born in 1948, this towering population of American chestnut trees was decimated. But as chief scientist of The American Chestnut Foundation, a nonprofit organization with 16 state chapters, Hebard’s work may herald the revival of this deeply rooted legacy.

Between 1904 and 1955, an Asian fungal pathogen known as Cryphonectria parasitica wiped out nearly four billion mature chestnuts. Only fledgling trees remained, perpetually resprouting from the same root before being besieged by the blight upon reaching maturity. A chance encounter ignited Hebard’s lifelong fascination with the genetics of blight resistance.

“I was working on a farm as an undergraduate at Columbia University when some heifer broke out of the pasture,” recalls Hebard. “As the farmer and I chased it down we came across a chestnut tree struggling to sprout. He told me the story about the blight, so I thought ‘I should do something about that.’”

After obtaining a doctorate from Virginia Tech, in 1989 he took a position in Washington County, Va., at Meadowview Research Farms, The American Chestnut Foundation’s new chestnut research and breeding station. In 2005, the foundation unveiled the potentially blight-resistant Restoration Chestnut 1.0 seedlings.

More than 100,000 of these American-Chinese hybrids have since been planted. Under the guidance of Hebard, and with the help of thousands of volunteers, each tree was hand-pollinated across six generations to possess the blight resistance of Chinese chestnuts and the statuesque appearance of American chestnuts.

“We weren’t around when the chestnuts were here, so we don’t always appreciate what’s missing,” says Dick Olson, who has volunteered with the foundation for five years.

Meanwhile, Hebard is already working on the next generation of seedlings. “It’s not as clear cut at this time that we have a great tree,” says Hebard, who cautions that judgment will require decades of observation. “But already it’s a good tree, it’s resistant. Taking part in that, and moving it along, is very satisfying.”

To learn more, visit acf.org. For information on Meadowview Research Farms’ 25th anniversary event on Oct. 11, call Dick Olson at 276-466-3130.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Hi Fred,

We may have some connections from strange places. My Father was born in Pequaming,Michigan and my Grandmother worked for the Hebards at the “big house” there. In fact she went to Philadelphia at least one summer with Mrs. Hebard. My Dad was a forester (Michigan State) and worked at TVA until he died in 1959. When I was a kid we stopped to see Mrs. Hebard at the plantation home on the river. We were greeted by her and her butler. It was a very memorable event that is still etched in my memory.

Thanks for your work on hickory trees. I was born in 1940 in E. Tennessee so do not remember them alive. However I do remember playing on their logs in the woods as a little kid and Dad telling me about what killed them.