Front Porch Blog

The U.S. House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources held a hearing on June 9 to consider several pieces of legislation related to coal mining. I testified along with two other witnesses from the Appalachian region. Together, we covered a range of topics from acid mine drainage and abandoned mine land (AML) sites, to the impacts of ongoing mountaintop removal coal mining.

Watch the full hearing.

John Dawes, executive director of The Foundation for Pennsylvania Watersheds, highlighted the importance of treating acid mine drainage as part of cleaning up AML sites. Acid mine drainage turns waterways rust-orange with dangerous pollution, and threatens the health of people and wildlife. Remediation of this pollution requires long-term water treatment facilities, and in turn, long-term funding.

The AML program has traditionally included an “acid mine drainage set aside” provision that allows states to set aside some AML funding for ongoing treatment of acid mine drainage.

Beyond the initial treatment infrastructure required, treating waterways contaminated with acid mine drainage typically requires many years of funding to maintain and operate the treatment systems. The infrastructure law passed earlier this year provided an extra $11.3 billion in funding for AML reclamation, but did not include a provision allowing states to set aside any of that funding for acid mine drainage treatment.

Without the ability to set aside some funding to maintain the systems for the long haul, states are reluctant to install the necessary treatment systems in the first place. The Safeguarding Treatment for the Restoration of Ecosystems from Abandoned Mines Act, or STREAM Act (H.R. 7283), would ensure that some of the money from the infrastructure law could be set aside in interest-bearing accounts to pay for the long-term treatment that will be required.

Ask your members of Congress to support the bipartisan STREAM Act!

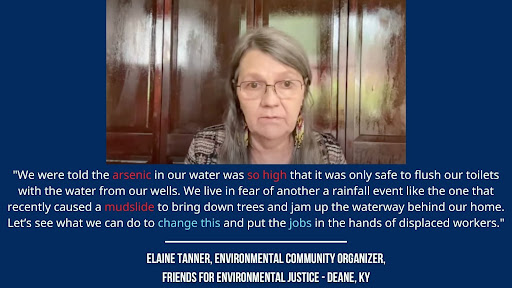

Elaine Tanner, a resident of Letcher County, Kentucky, and program director of Friends for Environmental Justice, took the stand before the House subcommittee to share her experience with the impacts of both historical AML land and more recent mining on her family’s land. The presence of both types of mine sites has not only had compounding negative impacts on land, streams and well water, but has also complicated the process of identifying which coal companies are responsible, which laws apply, and what funding is available.

“East Kentucky communities need help to move forward into a healthier and more fair future. We do not need more mountaintop removal coal mine permits granted in our region,” Tanner said. “We need the mines that are already here to be properly reclaimed.”

I testified about the ongoing impacts of mountaintop removal coal mining, and the backlog of mine reclamation that is jeopardizing cleanup.

Apart from the pre-1977 AML sites eligible for cleanup funding through the AML program, there are also over 950,000 acres of modern mines permitted under the 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act that still need reclamation. These mines are supposed to be reclaimed by the coal companies that hold the mining permits, but many companies are leaving this reclamation incomplete for years.

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act requires that coal companies secure reclamation bonds for mines, and was intended to prevent another wave of abandoned mines. But the extent of the reclamation backlog is now so large that as coal companies go bankrupt or otherwise walk away from reclamation obligations the bonding systems may not be funded well enough to guarantee cleanup.

The Revitalize, Enhance, and Nurture in Expanded Ways Our Abandoned Mine Lands Act, or RENEW Act (H.R. 7937), sponsored by U.S. Rep. Conor Lamb, would help to ensure that coal companies don’t shift the burden of cleanup to taxpayers and local communities.

The act would provide funding for the federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) to make grants to state mining agencies to fund reclamation at forfeited mines where the available bond does not cover the total cost of remediating the site.

In order to be eligible for grants, state agencies would need to show that they are addressing deficiencies in their bonding program and have made reasonable attempts to secure additional funding from the responsible coal company. Coal companies would not be eligible for this funding.

Despite the backlog of mines that need reclamation, states are granting more surface mine permits. For example, the Turkeyfoot permit is a pending surface mine permit from Alpha Metallurgical Resources, located in Raleigh County, West Virginia. It is another expansion of Alpha’s mines on Coal River Mountain.

That mine would cover over 1,000 acres, and include four valley fills. By any standards, it is a large mountaintop removal mine. The Appalachian Communities Health Emergency Act, or ACHE Act (H.R. 2073), sponsored by U.S. Rep. John Yarmuth, would disallow issuing mountaintop removal permits until the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services determines whether such projects pose risks to human health. Among many impacts, dust from mountaintop removal mines has been shown to contribute to the development of lung cancer.

The Coal Cleanup Taxpayer Protection Act (H.R. 2505), sponsored by Representative Matt Cartwright, would significantly strengthen coal reclamation bonding practices. It would require that states using alternative bonding systems like pool bonds demonstrate that such programs are financially sound based not just on previous performance, but also on a five-year forecast of market conditions, anticipated forfeitures and reclamation cost. It would disallow the use of coal mines and coal mining equipment as collateral for bonds. It would require the federal government to establish limitations on surety bonds to minimize risk. And it would disallow the use of self-bonding, which is when a coal company simply assures regulators it is capable of covering the cost of cleanup, and require existing self-bonds to be replaced with monetary bonds.

If passed, this bill would address many problems present in current state bonding programs. For example, it would require A&G Coal to replace its self-bonds at 20 permits in Virginia. A&G holds about $5.5 million in surety and cash bonds, and over $24 million in self-bonds. The state pool bond currently holds just over $10 million and covers over 100 other mine permits operated by other companies. If A&G were to forfeit its permits, the cost of reclamation at its sites alone may exceed the total pool bond and the available permit-specific bonds by as much as $94 million.

We’re excited to see the House Natural Resources Committee take a serious look at the issues still plaguing coal communities. The $11.3 billion Congress passed last year for AML cleanup is a huge step for reclaiming decades-old abandoned mine land, but it won’t solve any of the problems with current coal mining, or the modern regulatory system. The bills under consideration during the hearing would tackle a number of these problems, that, if left unaddressed, will place considerable burdens on coal communities in the form of environmental and public health impacts from unreclaimed mines.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Excellent recap of the need for legislative enforcement and appropriations needed just to clean up the messes and past abuses by coal strip miners. The recent horrors of flash floods in eastern KY further highlights the disrupted hydrological systems and loss of watershed forest cover and permeable soils in abandoned mine lands.

I can only hope your testimony before the committees and these legislative actions can finally begin to hold this industry accountable.

Kept up the good fight.