Front Porch Blog

For several years now, residents of Race Fork near Hurley, Virginia, have been complaining about thick clouds of dust in their community, courtesy of the trucks hauling coal off of the Laurel Branch Surface Mine, a 1,500-acre mountaintop removal site. Their complaints have prompted the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy (DMME) to have a look, and issue a citation every now and then, but in the eyes of at least 27 community members, who filed a joint complaint earlier this year, no effective remediating action has yet occurred.

Meanwhile the mine’s operator, Clintwood JOD, has advanced down the ridge onto the adjacent 300-plus acre Gobbler Spur Surface Mine. This prompted a new wave of complaints from people living along Lester’s Fork on the other side of the mountain. Some of these individuals have expressed alarm over sudden heavy flows of muddy water coming off Gobbler Spur when it rains, but the primary concern along Lester’s Fork is the frequency and intensity of blasts that shake homes and at times cast coal and rock dust out over the community.

Though these mines are operated by Clintwood JOD, they are permitted to Clintwood Elkhorn Mining Company (CEMC), a subsidiary of Cambrian Coal, which is currently in month 15 of Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings. Community members already face an uphill battle when trying to get a coal company to mitigate the impacts its mines have on the public’s health and well-being. But when the company is bankrupt, that hill gets a lot steeper.

At the Laurel Branch mine, trucks travel across muddy areas like this and then track large amounts of dust into the nearby community of Hurley. Image from a December 2019 DMME complaint investigation that resulted in the agency issuing a notice of violation to the mine operators. Photo courtesy of Virginia DMME

For one thing, companies that find themselves in bankruptcy may also lack the necessary resources, competency, or frankly even the will, to promptly address problems. Moreover, bankrupt companies enjoy the protection of what is known as an “automatic stay.” This is a court order that is intended to suspend the collection of a bankrupt entity’s debts, but that may also serve to shield derelict coal companies from grassroots efforts to enforce mining regulations.

There is an exception to the automatic stay, however, which allows police and regulatory agencies to carry out law enforcement actions regardless of whether the subject of those actions has declared bankruptcy. This means that while the residents of Race Fork and Lester’s Fork may not have any direct legal recourse to make Clintwood Elkhorn control the dust, runoff, and blasting impacts of its mines, the DMME fully retains its power to enforce state mining laws.

So then the question becomes, does the DMME feel that the law has been or is being violated on the Laurel Branch or Gobbler Spur strip mines? And if so, what actions is the agency willing to take to compel compliance? To answer these questions, we can examine publicly available documents such as citations, mine inspections and complaint investigations.

A short history of problems at the Laurel Branch and Gobbler Spur mines

Since 2017, the DMME has cited Clintwood Elkhorn 13 times for violating mining regulations on the Laurel Branch mine. Five of these dealt with trucks tracking dust and mud off the permitted haul roads and onto public roadways. The others dealt with discharges of pollutants into Race Fork, failing to control drainage and sediment, failing to meet reclamation requirements, not reporting required water quality data. In that same time, the permit received 4 cessation orders from the DMME. Two were for blasts that shot rocks and rubble beyond the permit boundary; one was for a release of acidic water, and the last was for a drainage control failure that caused damage to a home.

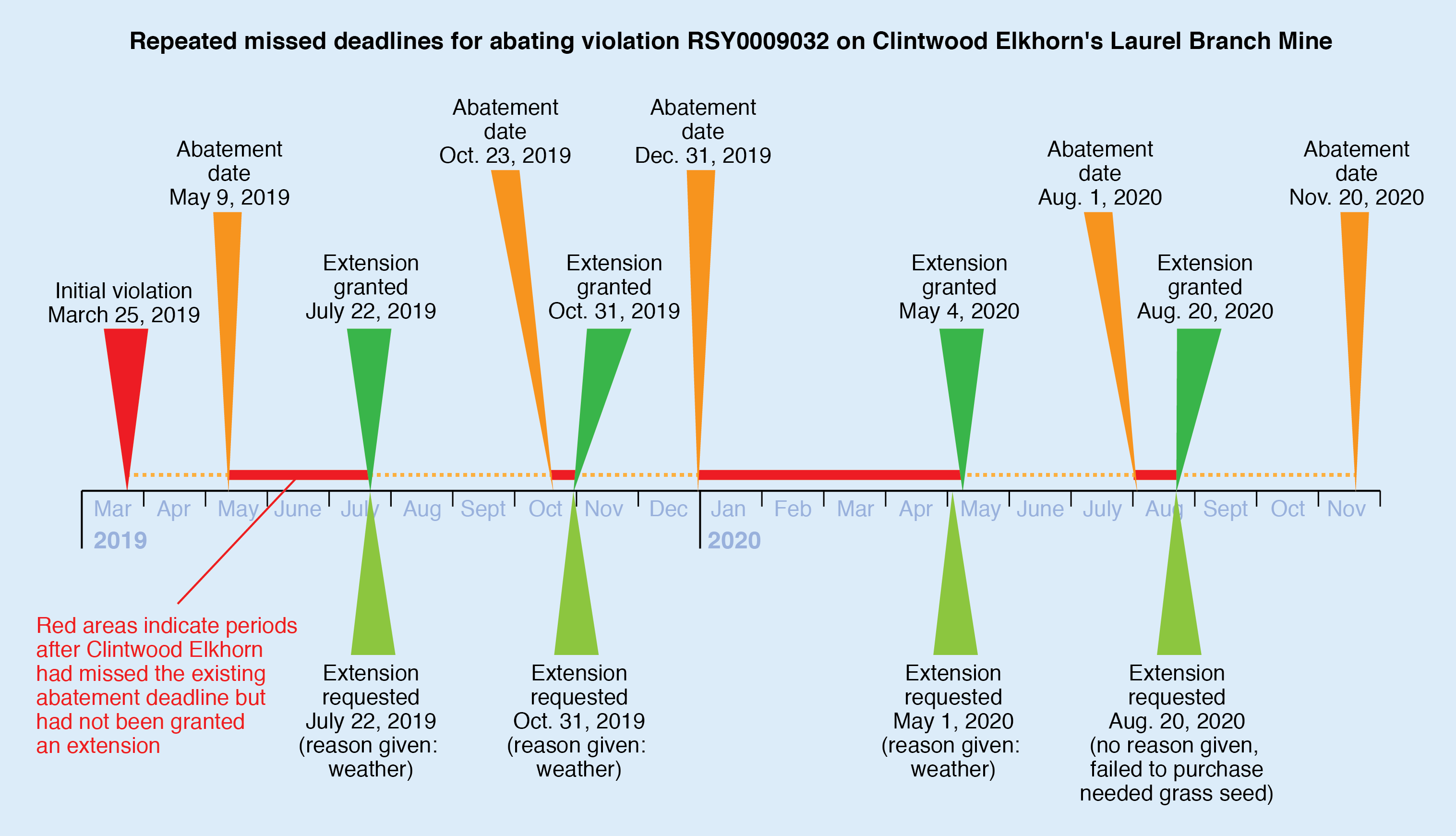

One March 2019 violation (RSY0009032) was issued for neglecting to reclaim disturbed areas concurrently with creating new disturbances. State law stipulates that such violations must be abated within 90 days, save for very few exceptions, such as when weather conditions get in the way. Otherwise, if that 90 day period passes and the violation still hasn’t been corrected, regulators would typically issue a Cessation Order. This is a more serious enforcement action prohibiting the continued extraction of coal from the site and moving the permit one step closer to revocation. The other option would be for the regulatory agency to enter into a compliance agreement allowing the company extra time to abate the violation. (Such agreements can be problematic, as is exemplified by a series of extensions between DMME and A&G Coal Corporation.)

In this case, Clintwood Elkhorn simply requested extension after extension of the initial abatement period. Sometimes these requests came as much as two months after the company had already missed the existing deadline. To date, the DMME has granted four extensions, with the current deadline set for November 20, 2020, about 17 months after the original 90 days. According to email exchanges between the company and the DMME, three of these extensions were requested due to weather conditions, and one was because the company had failed to purchase grass seed. Though Clintwood Elkhorn contends (and DMME accepts) that inclement weather was largely to blame for the nearly year-and-a-half delay in correcting this violation, it should be noted that weather conditions did not prevent Clintwood Elkhorn from extracting coal from the Laurel Branch mine during this period.

Since 2017, the DMME has cited the Gobbler Spur mine nine times, including two cessation orders. The mine’s infractions included releasing contaminants into adjacent creeks, failing to control drainage and sediment, and for not reporting required water quality data to the state.

Notably, on January 7, 2019, DMME found that Clintwood Elkhorn had violated the terms of its permit when it disturbed parts of the mine for which it hadn’t yet established sediment and drainage controls. The agency issued a cessation order at that time, stating that the disturbance could cause significant, imminent environmental harm. Just two days later, DMME issued a second cessation order as the regulators’ prediction came true and a landslide occurred, leading to extensive damage to adjacent property, with debris ultimately settling in Mile Branch, a tributary of Lester’s Fork. DMME then entered into a compliance agreement with Clintwood Elkhorn, detailing a 23 month timeline by which the company must correct the problem and clean up Mile Branch. However, according to DMME personnel, rather than actually remove the debris and remediate Mile Branch, the company is seeking the permission of the EPA and Army Corps of Engineers to simply leave the material where it lay.

Regulatory actions fall short

While the DMME has taken enforcement actions against Clintwood Elkhorn regardless of the company’s bankruptcy status, it is evident that the agency is willing to let a very long time pass before certain issues are resolved, and that resolution in the eyes of regulators does not necessarily bring relief to the mine’s neighbors.

It is also true that some community concerns just don’t correspond with actual violations of law, at least according to the DMME’s reading of the facts on the ground. This is often true with regards to blasting in particular, as anecdotal evidence suggests that blasting regulations have long failed to account for the safety, property, and quality of life of nearby residents.

With regards to the dust, the DMME has five times determined that Clintwood Elkhorn was not properly maintaining its haul roads. On those occasions, the agency compelled the company to lay fresh gravel, which partially and temporarily reduced the levels of dust in the air. But regardless of the state of the haul road, coal trucks become caked with dirt while they are on the mine itself. They then track that dirt onto the public roads where it dries up and becomes dust clouds that get stirred up and whipped around with every passing vehicle. The DMME has no jurisdiction over public roads, but community members contend that the agency does have the authority to require additional measures within the permit boundary, like truck washes or paved coal stockpile areas, that would help control dust in the community.

So where does this leave the families that live just downslope from these two mines? According to conversations with residents of these communities, some have given up on calling in complaints, and chosen to simply wait it out and pray for the best. Others continue to notify the DMME of their issues, hoping that more stringent enforcement will come at some point. In the meanwhile, the folks along Race Fork and Lester’s Fork live day to day with dust in the air, mud in the streams, and blasts that shake their homes as Cambrian’s bankruptcy reorganization slogs along.

Update 12/3/2020: Since we published this blog, the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy has approved yet another extension of the abatement date for violation RSY0009032 on Clintwood Elkhorn’s Laurel Branch Mine. The deadline is now February 18, 2021, nearly two years after the violation was first noted.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *