Front Porch Blog

Who cleans up the mess? This blog is part of a series examining how coal companies and state regulators are handling the mine reclamation problems tied to the industry’s decline. Read about the problems West Virginia is facing with ERP mines, how companies are playing hot potato with some of Blackjewel’s mine sites, and the threat posed by Justice family mines in Virginia.

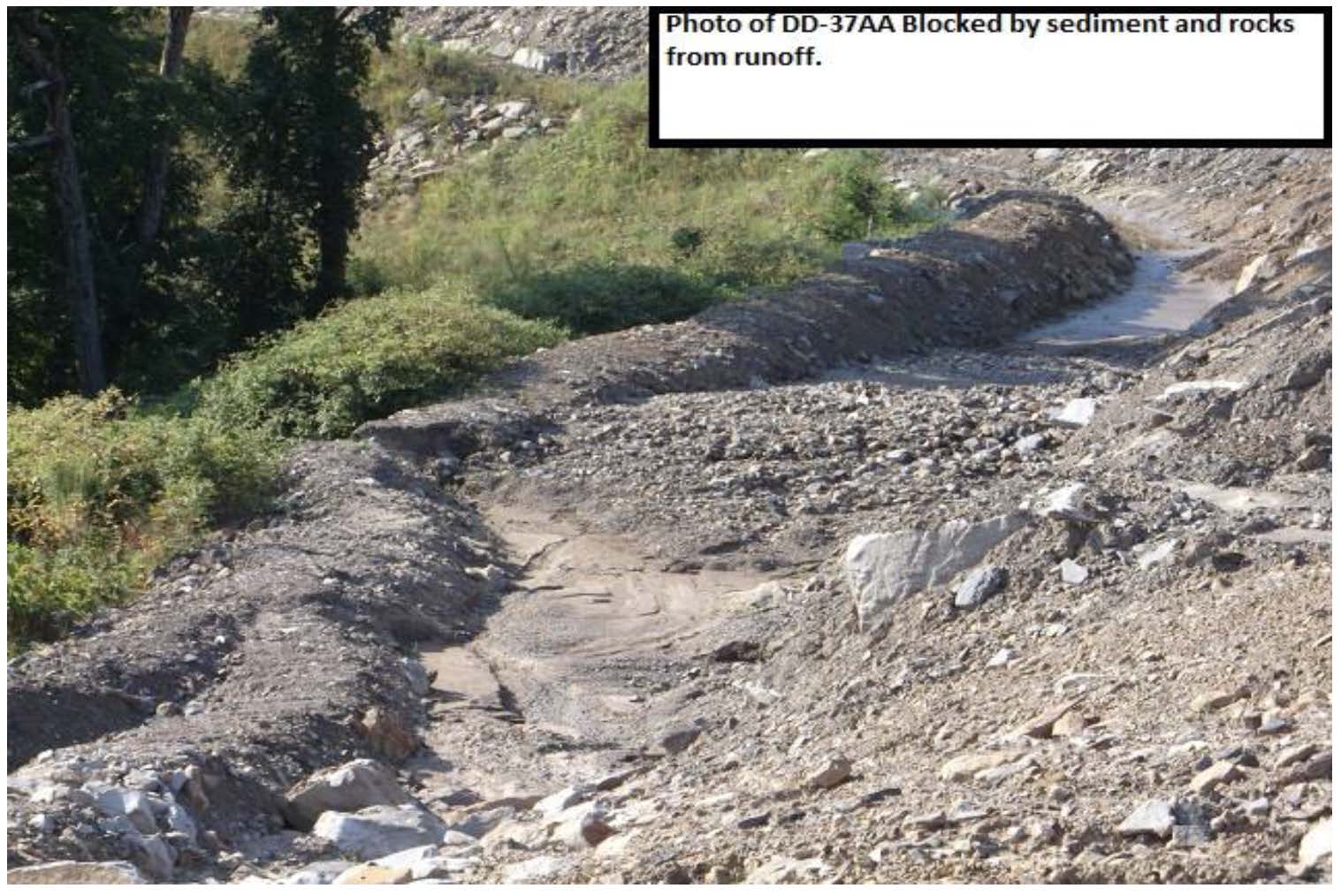

The ditches meant to contain runoff from the unreclaimed Aily Branch mine are clogged with sediment, which caused this berm to burst and send a torrent of mud and debris toward the Mitchells’ home this summer. Photo by Willie Dodson

According to a March 5 filing in the bankruptcy court by Blackjewel, an entity called Civil, LLC has agreed to purchase permits 1102080, 1102141 and 1102137. These operations collectively comprise 1,865 permitted acres of mountaintop removal and contour surface mining, with around 400 acres currently in need of reclamation. All of these permits have numerous outstanding violations of Virginia’s surface mining regulations.

Appalachian Voices first reported on this group of mines in September 2019, shortly after the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy (DMME) issued determinations of bond forfeiture on these and two other permits (one of which has since been sold, while the other remains in limbo). For several years before the bankruptcy, nearby residents had experienced uncontrolled runoff, mud, and debris washing down from the Aily Branch Surface Mine (permit 1102080) during heavy and even moderate rainfalls.

“I don’t know why [the state] let them go so many years without making them fix anything,” says Bobby Mitchell, who lives downhill from the Aily Branch mine. “The danger is where these sediment ponds get so full and bust loose. It’s happened two or three times in the past. There’s real muddy water been flowing pretty good here lately, too.”

At the time of the bankruptcy in summer 2019, sediment and drainage control structures on the Aily Branch mine were not functioning properly, and the situation had still not been addressed as recently as March 2020.

“When a company like Blackjewel goes bankrupt, environmental compliance is the first thing to be left to the wayside,” says Lyndsay Tarus, engagement coordinator for The Alliance for Appalachia, a coalition of regional and community organizations. “It shows how little they value the communities they operate in. They have just pillaged, and now we’re wondering who will deal with the mess they’ve left behind. ”

When will cleanup finally happen?

At the Aily Branch surface mine, a ditch meant to help control runoff is clogged with sediment and rocks. Image from the Virginia DMME Notice of Violation issued against Revelation Energy on Aug. 20, 2019.

It is not uncommon for a coal mine to be permitted to one company and operated by another. Reclamation and long-overdue environmental compliance work can commence as soon as Civil LLC’s operator status is approved by the DMME, but coal extraction will have to wait until after the agency approves the transfer of each permit. An exact timeline for transfer of operator and permittee status to Civil for all of the mines is currently unknown, but Bledsoe stated that the company is “actively pursuing measures to transfer the permits.” According to a database maintained by the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE), Civil has been listed as an operator for the Aily Branch mine.

Who is Civil, LLC?

Civil, LLC is owned by John Quintrell, who also serves as vice president of JRL Coal. Civil, which appears to have only been a trucking company until September 2019, holds no mining permits itself, but is listed as the operator on ten coal mines, mostly in Kentucky where the company is based. Five of the mines Civil operates are permitted to Quintrell’s other company, JRL.

The Kentucky Division of Mine Reclamation and Enforcement has issued 32 notices of non-compliance to JRL since January 2019 for issues ranging from sediment and drainage problems to water quality infractions. According to Kentucky’s Surface Mining Information System, six of these remain unresolved as of April 7.

Federal law prevents a coal company from receiving any new or transferred mining permits if that company, an affiliated company, or an individual officer associated with it is responsible for outstanding violations. The unresolved problems on JRL’s and, by association, Quintrell’s, mines are unlikely to prevent Civil’s acquisition of the Virginia permits however, as violations are not typically considered ‘outstanding’ if the appropriate agency has granted a timeline for compliance and/or administrative review of the initial citation, as is true for these citations.

Is this the best we can do?

At this stage in the Blackjewel bankruptcy, the mines that have still not sold don’t have much profitability left in them. In fact, the court uses the term “de minimis” to describe this inventory, which literally translates as “too trivial or minor to merit consideration.” And at this point in the steep decline of the Appalachian coal industry, there aren’t a lot of reliably law-abiding and solidly solvent companies out there looking to purchase mines, particularly “trivial” ones. So Civil, LLC, even with its owner’s troubling record of regulatory non-compliance, may represent the last, best hope that an actual coal company will reclaim Aily Branch and its neighboring mines.

If for any reason the sale and transfers don’t go through, or if Civil fails to complete the needed work, the liability (bonded at around $30 million) will fall to Indemnity National Insurance Company, the surety bond provider for these permits, which may be trying to avert its own financial ruin.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *