Front Porch Blog

Who cleans up the mess? This blog is part of a series examining how coal companies and state regulators are handling the mine reclamation problems tied to the industry’s decline. Read about the problems West Virginia is facing with ERP mines, a potential buyer for three bond-forfeited Blackjewel mines, and the threat posed by Justice family mines in Virginia.

This photo from October 2018 shows polluted runoff from a mine near Honaker, Va. The mine is one of the 22 “hot potato” permits, and it’s not yet clear who will take responsibility for reclamation. Photo courtesy of Virginia DMME.

In Virginia, the bankruptcy created an uncertain future for 71 mining permits. Twenty-seven of these have been purchased and transferred to other companies, and 12 are in the process of being transferred, according to the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy (DMME).

This leaves 32 Virginia permits still in limbo. The ownership of 22 of these permits is currently being debated by Virginia regulators, a surety insurance company, and two coal companies — Rhino Energy and Eagle Specialty Materials — none of whom want to be left with the associated mine reclamation obligations. It’s like a game of hot potato, but what is being tossed around is the responsibility to repair land and water damage.

At issue is the interpretation of a jumble of legalese that references the subdivision of Blackjewel’s Appalachian mines, which mines are included in each subdivision, and which mining permits, leases and mineral rights were transferred during sales.

It’s a lot to untangle, but here’s something of a timeline:

On July 1st 2019, Blackjewel and Revelation declared bankruptcy. On that same day, Jeff A. Hoops, then head of Blackjewel and former head of Revelation, filed a declaration outlining facts of the bankruptcy. In that document, Hoops described the mines that were acquired, largely through previous bankruptcies, and how the Eastern permits were grouped into various subdivisions:

“Blackjewel’s assets were primarily acquired from struggling coal mining firms and then revitalized… The Northern subdivision assets were acquired from Hylton, the BHL subdivision

assets were acquired from James River, the Black Mountain subdivision assets were acquired from Alpha, and the Virginia subdivision assets were acquired from Suncoke.”

Many of those subdivision names continued to be used during the auction proceedings, though the exact makeup of each subdivision remained unclear, at least to those outside the process.

On August 23, 2019, the bankruptcy court approved the sale of 11 Virginia mining permits to Rhino Energy. Along with these operations, the sale agreement also conveyed to Rhino any “…inventory located within the Virginia Subdivision property control whether or not contained within, on, or under the mine permit(s) listed above.”

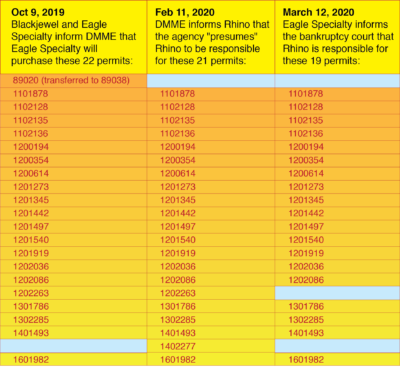

Click to enlarge. The mine permits in dispute are largely the same, though there are a few discrepancies between the lists used by various entities.

On October 4, 2019, the court approved the sale of two large Wyoming mines included in the bankruptcy to Eagle Specialty Materials. But on October 7, Blackjewel filed an emergency motion to transfer the 135 remaining permits across the company’s Eastern division to Eagle Specialty Materials as well. This additional transfer became necessary because Lexon Insurance Company would be providing $237 million in reclamation bonds for the Wyoming permits (according to the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality), but was already responsible for about $100 million in bonds for Blackjewel’s remaining Eastern sites. In order to reduce their own financial risk, Lexon required Eagle Specialty to also assume reclamation obligations for the Eastern permits and find a new surety company to provide the reclamation bonds for those permits.

Subsequently, on October 9, Blackjewel notified the DMME that it had relinquished mining rights to Eagle Specialty for 21 of the 22 hot potato permits. According to communications between Appalachian Voices and DMME staff, this had initially given the agency the impression that Eagle Specialty Materials would eventually assume ownership of these permits, after settling certain lease complications with Rhino.

This impression had changed however, by February 11, 2020, when Randy Casey, director of the DMME’s Division of Mined Land Reclamation, sent a letter to Rhino stating, “It has come to our attention that through the Blackjewel, LLC and associated companies bankruptcy proceedings, Rhino Energy, LLC… has obtained the leases, properties, equipment and other resources in the area of the attached list of Virginia permits.” The attached list includes… you guessed it… 21 very hot potatoes. The letter goes on to explain that the state of Virginia presumes the acquisition of those permits to also include all the associated reclamation obligations.

In a response dated March 12, 2020, Rhino contested the DMME’s assertion that they must assume responsibility for the permits in question, citing a clause in the original sale agreement which states, “Buyer will not assume any reclamation obligations associated with any permit not identified [in this sale agreement].” They further argued that the agency has no authority under Virginia or federal law to make such a presumption in the first place.

Adding to the precariousness of the situation, are indications that neither Eagle Specialty nor Rhino may actually be well-suited to reclaim these mines. In its annual report, dated March 27, Rhino disclosed that it is likely to become insolvent within the calendar year as COVID-19 exacerbates the companies’ existing problems tied to the long-declining demand for coal. Meanwhile, Eagle Specialty’s parent company, and the previous associations of its corporate officers, carry compliance histories ranging from checkered to abysmal. The company is a fully-owned subsidiary of FM Coal, which has had 58 violations stretched across 15 of its 20 mines, all in Alabama, over the past three years. And Eagle Specialty’s manager, Jeoffrey Pillon, and director, Daniel Baker, both previously served as officers for Blackjewel during that company’s disastrous tenure.

So to recap: There are 22 mining permits in Virginia in need of cleanup with a combined total bond amount of over $16 million — and the true cost of reclamation will likely be much higher. Lexon Insurance Company says Eagle Specialty Materials has to take them. The Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy says Rhino Energy has to take them. Eagle and Rhino both say, nah.

As regulators and insurance companies scramble to make sure some coal company or another is put on the hook for reclamation of these mines, no one is looking to former Blackjewel CEO Jeff Hoops to clean up his own mess.

Why is this? After all, it was Hoops’ corporate mismanagement and apparent disregard for workers, the environment, and the law that created this disaster in the first place. What’s more, federal surface mining law explicitly gives regulators the right to pursue the personal assets of a culpable corporate officer in order to fund reclamation when the officer’s corporate entity has failed to do so. Amidst the chaos of Hoops’ cascading house of cards, it may be time for state agencies to exercise the full extent of their authority by suing this coal baron directly, in order to seize the necessary funds to heal the extensive scars he has inflicted upon the land.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment