A Burning Issue: The Health Costs of Coal Ash

By Elizabeth E. Payne

After laboring to clean up the nation’s largest coal ash spill, many workers became sick and 17 died, alleges a lawsuit filed in July on behalf of more than 50 workers and workers’ survivors.

The lawsuit was filed against Jacobs Engineering, the company hired by the Tennessee Valley Authority to clean up the 2008 disaster, which occurred when a dam failed at the TVA’s Kingston coal-fired power plant in Harriman, Tenn. More than 1.1 billion gallons of coal ash sludge spilled across rivers, homes and fields. According to the Knoxville News Sentinel, the workers sent to clean up the toxic substance were not provided any protection or warning about the dangers of coal ash exposure.

David Hairston was born and raised in Walnut Cove. Photo by Dot Griffith. He worries about the health effects to his community caused by Duke Energy’s Belews Creek Power Plant.

During the cleanup, 4 million cubic yards of the toxic ash was transported from Harriman, Tenn., — a town that is 90 percent white and middle class — to a landfill in Uniontown, Ala., which is 90 percent African American with 45.2 percent of its population living below the poverty line. Soon after, local residents and landfill employees in Uniontown began experiencing health problems.

Every year, the nation’s coal-fired power plants produce 130 million tons of coal ash; much of the ash that has accumulated over the past decades is stored in unlined impoundment ponds scattered across the country — some of which are more than a thousand acres large.

This toxic byproduct of burning coal for electricity contains concentrated amounts of the same heavy metals present in coal, including mercury, arsenic and lead. These toxic heavy metals can increase risks to human health by leaching out of the impoundment ponds into the surrounding soils and groundwater. Even greater risks accompany the failure of these impoundments.

According to a 2014 study by Physicians for Social Responsibility and Earthjustice, the fine particles in coal ash can cause significant health problems when inhaled, such as respiratory illnesses, heart disease and an increased risk for stroke.

For North Carolinians living near Duke Energy’s coal ash locations, such studies seem to confirm their fears.

Living in the “Danger Zone”

According to David Hairston, many folks describe Walnut Cove, N.C., as the ‘danger zone.’

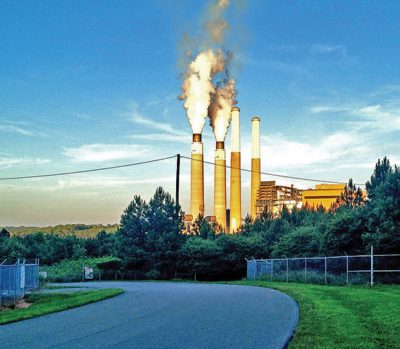

The town sits just a stone’s throw west of Duke Energy’s Belews Creek Power Station and its large coal ash impoundment pond.

While Hairston now lives about eight miles away from the power plant, he was born and raised in Walnut Cove, and his mother lived there until she passed away three years ago.

“You can travel from my mom’s house to the steam station, and there’s homes on both sides of the road through that five-mile drive,” Hairston says. “And there’s not a house you can pass by that’s not somebody either battling [cancer], beat cancer or died from cancer on either side of the road. Or if it’s not, somebody that’s living on an oxygen tank because of respiratory problems.

“The closer you live to the coal ash pond and the coal ash fill, the more sickness you can see,” he continues.

On Feb. 2, 2014, a pipe beneath a coal ash pond at another Duke power plant in Eden, N.C., ruptured, spilling more than 39,00 tons of coal ash into the Dan River. The Dan River flows through Walnut Cove on its way to Eden.

Following the spill, North Carolina regulators passed the Coal Ash Management Act which required, among other things, that drinking wells within 1,500 feet of the state’s 34 coal ash impoundments be tested for contamination.

As a result of that testing, more than 300 homes across the state received “do not drink” letters from the state’s Department of Health and Human Services, including several homes near the Belews Creek power station. Most of those wells contained high levels of two carcinogens, vanadium and hexavalent chromium.

The “do not drink” orders were later rescinded by the administration of then-Gov. Pat McCrory, which asserted that higher levels of these toxins were in fact safe (see sidebar). The uncertainty weighs on the families living near these coal ash sites.

“How would you feel, as a mother of a newborn child [and you] can’t afford to move, that’s scared to bath your child in water, that you may be killing it, or you may be making it sick or make it have a disability by the time it matures because it’s immune system is so weak,” says Hairston. “Or having to raise a child down there breathing that air. Because unfortunately what you inherited from your parents, what they worked years for, a home, that is valued at nothing, and you can’t afford to go anywhere. That is what they’re dealing [with].”

Facts in a Sea of Uncertainty

After residents came to them asking for help understanding the results of their state-required water samples, researchers from the University of North Carolina launched their “Well Empowered” project to assist communities across the state, who, for any number of reasons, are concerned that they may be exposed to heavy metals through their private wells.

Researchers at UNC have been studying well water in the state for more than a decade. This project is a collaboration between university researchers in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering and the Institute for the Environment, and has been supported by community members and environmental nonprofit organizations, including Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this paper.

“About three million North Carolinians get their water from a well. So [water quality] isn’t an abstract question, this is really important to North Carolinians who don’t have any other options for water, for drinking water,” says Dr. Andrew George, the community engagement research associate at the Institute for the Environment.

During the initial phase of the project, the group distributed surveys and collected water samples from homes in Walnut Cove and Goldsboro, N.C., both located near coal ash ponds. But they hope to broaden their research and help more people.

Members of ACT Against Coal Ash living near Belews Creek, including David Hairston (near right), meet to strategize how to clean up the coal ash near their homes. Photo courtesy of Appalachian Voices.

“We are starting in specific areas because the communities approached us. Those were the communities that had greatest concern,” says Dr. Rebecca Fry, a biologist and toxicologist in UNC’s Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, whose research focuses on the health effects from exposure to heavy metals.

“This study is really about helping people to have access to testing their water samples, helping them interpret the results from the inorganic assessment that we’re doing.” she says. ”We’re looking at a whole panel of metals, a whole panel of inorganics, and helping them interpret what the results mean.”

For communities that received official “do not drink” letters but were later told their water was safe to drink, getting facts they understand and trust can be a relief.

“We’re an independent, third-party research team, and now that we’ve gotten these results out there, that help provide a better understanding of what’s going on, it seems that the community has reacted very positively,” says George. “Even though some of the results aren’t necessarily what they were hoping for, at least they trust the results a little bit better.”

TVA Ordered to Clean Up Gallatin Coal Ash

On Aug. 4, a federal judge ordered the Tennessee Valley Authority to excavate the coal ash stored at its coal-fired Gallatin Fossil Plant in Gallatin, Tenn., and move it to a lined landfill. The ash currently sits in unlined impoundments above porous karst limestone.

The ruling came as a result of a Clean Water Act lawsuit filed by the Tennessee Scenic Rivers Association, represented by the Southern Environmental Law Center, and co-plaintiff Tennessee Clean Water Network. At press time, the TVA had not announced whether it would appeal the decision.

Because of concerns raised by community members, the team is now sampling water both from the well and from the faucet, to ensure that pipes are not polluting the water as they were in Flint, Mich. They are also taking soil samples since many residents were concerned about the safety of their gardens.

The team is beginning to receive results for the 40 homes sampled in Walnut Cove and nearly 20 houses sampled in Goldsboro. When results are returned to the residents, the UNC team provides them with information about any heavy metals that were found in their water, suggests what — if anything — needs to be done to make the water safe, and answers any questions the residents might have.

“For many of these metals, the most important thing for the homeowner is to know whether or not they’re present and at what levels,” says Fry. “That’s what we’re aiming to help with.”

For communities living near the state’s coal ash ponds, having a nonpartisan group of scientists provide facts about the quality of their drinking water can provide peace of mind, but it’s only one piece of the complex health puzzle they’re dealing with.

But for Hairston, even the impact of small amounts of contaminants need to be taken seriously.

“People consuming it with their water, out of their garden food and breathing it through the air, over a 40-year period of time, it takes a toll on your health,” he says.

N.C. Water Filtration Standards Set

After the February 2014 disaster at Duke Energy’s power plant in Eden, N.C., that resulted in 39,000 tons of coal ash spilled into the Dan River, state regulators passed the Coal Ash Management Act. The rule, together with a 2016 revision, mandates that Duke Energy provide access to clean drinking water to every household that is reliant on well water within one-half mile of a coal ash impoundment pond. Many affected communities, however, such as Walnut Cove, lie outside this half-mile radius.

To meet this requirement, Duke can either connect households to municipal water or provide wells with a filtration system capable of removing any unsafe contaminants.

In July 2017, the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality issued performance standards for these filtrations systems. But the standards do not require testing specifically for hexavalent chromium, one of the carcinogenic heavy metals found in the well water of nearly 200 homes that received “Do Not Drink” letters from the state’s Department of Health and Human Services in 2015. Instead, they allow for all types of chromium at levels significantly higher than that recommended by scientists at DHHS.

The allowable level of vanadium, another carcinogen identified in well-water samples, is under review.

While running for governor, Roy Cooper criticized then-Gov. Pat McCrory for overturning the health department’s 2015 standard of no more than 0.07 parts per billion of hexavalent chromium and replacing it with the far less protective standard of 10 parts per billion of total chromium when the administration rescinded the “Do Not Drink” letters.

After the Cooper administration adopted the same standard, which is 140 times higher than state scientists recommended in 2015, McCrory was quick to note the hypocrisy.

According to a review of DHHS emails by the Winston-Salem Journal, the more lenient standard allows for “a lifetime cancer risk that runs between 1 in 7,000 at best and 1 in 700 at worst.” The stricter standards represent a 1 in a million chance of developing cancer for an individual with a lifetime of exposure.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

One response to “A Burning Issue: The Health Costs of Coal Ash”

-

I lived in Belmont NC right at Allen plant and very healthy lady. Sick at age 40 with autoimmune wengers granulomotosis. It mimics the coal ash, and I know duke had poisoned me. I hope I live to see criminal charges, for nit warning us.

Leave a Comment