Front Porch Blog

TVA’s Paradise coal plant in Muhlenberg County, Ky., relies entirely on coal from the Illinois Basin, which includes mines in western Kentucky. Recently, utilities in the Southeast have looked beyond Central Appalachia, even to reserves within a day’s drive, to purchase cheaper coal.

The Tennessee Valley Authority’s Paradise Fossil Plant sits on the banks of western Kentucky’s Green River. The largest coal plant in the state, Paradise consumes approximately 7.3 million tons per year — none of which comes from Central Appalachian coal mines.

Although TVA recently announced it was cutting almost all of its use of Central Appalachian coal, a spokesperson for the utility pointed out that Paradise will still receive coal mined in Kentucky. But that portion of TVA’s coal purchases will be from mines in Kentucky’s western coalfields, just a few hundred miles from most of the state’s Appalachian coal-producing counties. Even just a day’s drive apart, the two reserves have dramatically different outlooks.

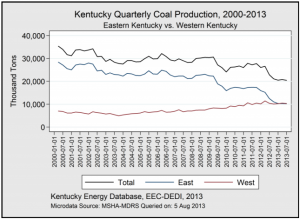

According to the most recent Kentucky Quarterly Coal Report, between April and June of this year, western and Eastern Kentucky coal mines each produced around 10 million tons of coal. But on a longer timeline, production and employment in Kentucky’s western counties have steadily increased while the state’s Central Appalachian mines have suffered.

Last year, Union County, which borders Illinois, overtook the easternmost Pike County as Kentucky’s leading coal producer — reinforcing the Illinois Basin’s growing importance to the state’s coal economy.

In the second quarter of 2013, coal production in western Kentucky exceeded production in the states most prolific Appalachian coal-mining counties by 1 percent. Click to enlarge

Central Appalachian coal now costs as much as $20 more per ton than coal from the Illinois Basin. As a result, even utilities in the Southeast that have historically purchased Central Appalachian coal are looking beyond the region for their coal purchases.

Back in 2009, industry experts and observers pointed to the coal rush resulting from the rebirth of the Illinois Basin, of which western Kentucky coal mines are a part. Advances in the technology and affordability of upgrading power plants were rapidly bringing dormant coal reserves deposits back online.

“I guess we can call it the rebirth of coal,” David Jones, a former miner living in Ohio County, Ky., told the Associated Press in 2010 — a time when the prospects in Central Appalachia were looking increasingly grim. Suddenly, coal mining giants including Peabody Energy were shedding Appalachian mines and betting big on the Illinois Basin.

Also a top producer in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin, Peabody touts its Bear Run Mine in Indiana for being the largest surface mine in the eastern United States with an annual capacity of nearly 8 million tons — still just a fraction of the 100 million tons that comes from Arch Coal’s Black Thunder Mine complex in Wyoming.

But high transport costs mean that more than the Powder River Basin, which receives its fair share of publicity for its massive mines and output, the Illinois Basin is emerging as the real winner in the battle for Central Appalachian coal’s lost customers.

The Tipping Point

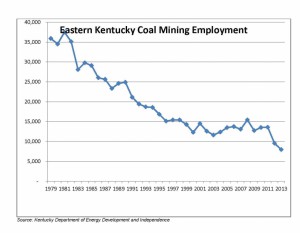

As Eastern Kentucky’s mining communities endure the shift to their western counterparts, they’re suffering more than any other coal-producing region in the United States. As of July 2013, an estimated 12,342 people are employed at Kentucky coal mines — the lowest level recorded since the commonwealth began keeping mining employment statistics in 1927.

Most recently, James River Coal and Alliance Resource Partners have announced layoffs and furloughs of 667 employees at Eastern Kentucky mines due to continued weak demand for coal in the U.S. and abroad.

Eastern Kentucky has been called the “ground zero” of coal’s decline. After losing nearly 6,000 coal jobs since the beginning of 2012, the region may finally be reaching a tipping point. Click to enlarge.

Since the beginning of 2012, Kentucky has lost 6,000 jobs in the coal industry. In West Virginia, coal employment declined by 3,400. Appalachian Voices director of programs, Matt Wasson, recently told SNL Energy that the disparity in job losses is further proof that low natural gas prices and competing reserves were to blame, not the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s intention to regulate carbon emissions from new power plants.

While Illinois Basin producers are ramping up production in order to pick up market share from Central Appalachian coal operations, weak demand is still likely to impact mines in Western Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois.

In the meantime, unemployed miners in Appalachia are willing to go west as long as there is work. Others in Eastern Kentucky, Frankfort and across the state are searching for longer term solutions. And, at least it seems, the real causes of the economic turmoil plaguing Kentucky’s Appalachian counties are finally being placed front and center.

Earlier this month, the Mountain Association for Community Economic Development released a report calling on state legislators go beyond unsuccessful “piecemeal projects” by setting up and overseeing the Appalachian Planning and Development Fund aimed at boosting Eastern Kentucky’s economy.

“The loss of so many coal jobs and our diminishing severance taxes are on everyone’s minds,” MACED’s president, Justin Maxson, said in a statement announcing the report. “As our resources become scarcer, it’s even more important that we spend them as wisely as possible. The longer we wait to act, the deeper the challenge becomes.”

Read more posts in this series:

The MACED report proposes dedicating 25 percent of Eastern Kentucky coal severance tax dollars to a single fund. According to Jason Bailey, the director of the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy and MACED’s research and policy director, a portion of that money would be spent annually to begin implementing the plan. The rest would go into a permanent endowment and be available for development strategies.

“We don’t know how long coal will last in our region, and its decline could become even more precipitous than it has been recently.” Bailey recently wrote. “But the next 10 years are an opportunity. Will we start the process of planning and investing in the region’s economic future? Or will our communities follow the industry down the hole that’s been dug over the last century?”

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *