Front Porch Blog

To meet current U.S. coal demand through surface mining, an area the size of Washington, D.C. — about 68 square miles — would need to be mined every 81 days, according to a new study.

We talk a lot about the external costs of mountaintop removal. And by understanding the true costs that coal puts off on the landscapes, water and communities of Central Appalachia, it’s abundantly clear that the costs far outweigh the benefits to all but a few.

But still we hear arguments about the need for a balance between the environment and the economy.

As elected leaders and industry representatives delude themselves and others, yet another study has concluded that mountaintop removal is simply not worth it. Here’s the simple takeaway from the conclusion of “The Environmental Price Tag on a Ton of Mountaintop Removal Coal”: Tremendous environmental capital is being spent to achieve what are only modest energy gains.

The study’s author, Brian D. Lutz, writes that while many studies have documented the severity of surface mining’s impacts on local ecosystems, less attention has been given to comparing the extent of mountaintop removal’s environmental impacts to the economic benefits of coal as an energy source. According to Lutz, an assistant professor at Kent State who began the study during his postdoc at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment last year, “This is a critical shortcoming, since even the most severe impacts may be tolerated if we believe they are sufficiently limited in extent.”

To accurately measure the extent of land disturbance against coal production, Lutz and the studies co-authors took county-level coal production data for 33 counties in eastern Kentucky and 14 counties in southern West Virginia. They compared this data to satellite imagery and known mine delineations that extended back to 1976.

Back in 2007, Appalachian Voices contracted with SkyTruth to compile much of this data. We’re thrilled that it has been used to educate others and build a better case for ending mountaintop removal. What’s more, the original data underestimates the amount of land disturbed by mountaintop removal by up to 40 percent in some areas, according to a follow-up mapping study conducted in 2009.

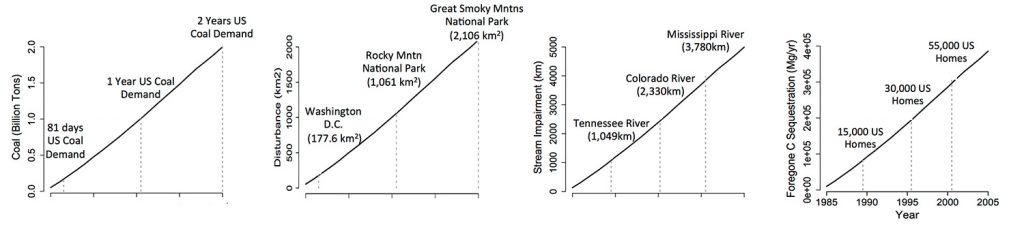

Based on the acreage of Appalachia already surface mined and the miles of streams already impaired, these graphs show what would be sacrificed if current demand for coal was met with mountaintop removal alone. Click the image to enlarge.

The conclusions drawn from those comparisons are laid out in simple terms most of us can understand and even visualize. Check out the graphs above for another representation of the environmental toll required to meet coal demand for two years with surface mining. Here’s how a press release from Duke University sums up the study:

To meet current U.S. coal demand through surface mining, an area of the Central Appalachians the size of Washington, D.C., would need to be mined every 81 days. That’s about 68 square miles — or roughly an area equal to 10 city blocks mined every hour.

A one-year supply of coal would require converting about 310 square miles of the region’s mountains into surface mines, according to a new analysis by scientists at Duke University, Kent State University and the Cary Institute for Ecosystem Studies.

Creating 310 square miles of mountaintop mine would pollute about 2,300 kilometers of Appalachian streams and cause the loss of carbon sequestration by trees and soils equal to the greenhouse gases produced in a year by 33,600 average U.S. single-family homes.

We know that Appalachian forests, as denuded as they are, serve as a carbon sponge. At least they have for millennia. A report from earlier this year found that mountaintop removal could turn Appalachia from a carbon sink to a carbon source in the next 12 to 20 years. Lutz’s study breaks it down further.

Based on the carbon sequestration potential of Appalachian ecosystems it would take approximately 5,000 years for any given hectare of former mines reclaimed to grassland to sequester the carbon released from combustion of the coal removed from that hectare, that is, assuming the ecosystem could persist over that time period.

Lutz writes that “the scientific community has adequately demonstrated the severity of surface mining impacts.” We agree, but also have found that facts only go so far once they’re met with the denial of Appalachian legislators in accepting the true costs of mountaintop removal. Nonetheless, here we have it, again: mountaintop removal is bad energy policy, devastating to the environment and the regional economy, and, as we’re beginning to understand more, a double whammy on the climate. It’s a mantra we’ll repeat until we win.

In light of the amassing academic research, especially research like Lutz’s, which should speak to the pragmatic and business-minded as much as the environmentally conscious among us, we have to wonder what it will take for the most ardent supporters of mountaintop removal to see reason.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *