Appalachian Beekeepers Protect Honeybee Health

By Hannah Gillespie

Richard Reid began beekeeping in Blacksburg, Va., in 1973 when his landlord asked him to tend to a few hives on the property. To learn the practice, Reid took classes from an entomologist at Virginia Tech. Now, he owns and operates Happy Hollow Honey, which consists of 100 to 250 colonies.

However, his journey hasn’t been without struggle.

In 1995, Reid gave up beekeeping for a time after parasitic varroa mites completely wiped out his bees.

“Shortly thereafter, a swarm moved in and actually lived there for 12 years without me touching them or interfering with them at all,” says Reid. “So I thought the bees were doing pretty well with varroa mites. Since I always really liked [beekeeping], about 10 years ago I got back in it again. And this time, much more intensively than prior to that. So I have been expanding since 2008 and this is sort of the new phase of beekeeping for me.”

Other long-term beekeepers echo this rocky timeline, full of extreme losses and gradual recoveries. Since the late 1980s, honeybees’ health has suffered due to a variety of factors, including parasites, pathogens, pesticides and poor nutrition.

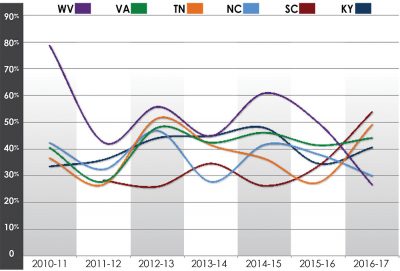

According to The Bee Informed Partnership, a nonprofit public research collaboration, the number of bee colonies in the Appalachian region has been declining by roughly 25 percent each year since 2010. With recent honey bee losses and developments in treatments, the role of informed beekeepers is increasingly important. At the same time, there is a growing demand for products from the hive, including local honey.

Charlie Parton has kept bees for nearly 40 years in Maryville, Tenn. In the past two decades, Parton has worked to expand his colonies and served two terms as the president of the Tennessee Beekeepers Association. Now, he sells honey and honeybees.

“An old beekeeper used to tell me, ‘some people are bee-havers and some are bee-keepers.’ And back then, you could be a bee-haver because we didn’t have all the issues with mites and maybe some of the pesticides from emissions,” Parton says. “So basically the bees thrived, [and] we had to do very little as far as treatments or anything like that. It was just a completely different world in beekeeping then compared to now … unlike today where [beekeepers have] got to be on top of every new development.”

Is it Colony Collapse Disorder?

Annual Honeybee Colony Loss in Appalachia: Trends of annual honeybee colony loss in Appalachia from 2010 to 2017, data provided by the Bee Informed Parnership

The term “colony collapse disorder” emerged in 2006 to describe the phenomenon where the majority of adult worker bees disappear from the hive.

James Wilkes operates his family-owned Faith Mountain Farm in Creston, N.C., where he sells honey and baked goods and has kept bees for 11 years. He is the CEO of Hive Tracks, a recordkeeping application for beekeepers, and is also a computer science professor at Appalachian State University.

Wilkes says that after a hive experiences collapse disorder, “usually there’s brood left and a queen and a few adult bees, whereas two weeks before there was a bee population in the hive and all the pieces [were] functioning well. You know you have done everything that you normally do and still you experience loss.”

In a 2012 article in the North Carolina State Beekeepers Association’s publication Bee Buzz, N.C. State University Extension Apiculturist David Tarpy states, “When it comes to recent findings dealing with honey bee health, these reports can actually be oversimplified, where anything dealing with honey bee mortality is immediately equated with [colony collapse disorder]. This is just simply not the case!”

James Wilkes echoes the sentiment that the phrase “colony collapse disorder” is overused.

“Honey bee health is still a big issue, honey bees are still dying, but one thing that’s happened is beekeepers are pretty creative,” says Wilkes. “Beekeepers have responded to the losses by replacing those losses, by growing more bees, and the bee population themselves have recovered and not continued to decline. It’s kind of becoming the way that you keep bees. You are intimately involved.”

Threats to the Hive

The U.S. National Agricultural Statistics Service found parasitic varroa mites to be the primary colony stressor in 2016.

According to Kentucky State Apiarist Tammy Horn Potter, the varroa mite arrived in the United States in the late 1980s. The mite lives on, feeds on and transfers viruses to the bee at every life stage. Bees are defenseless to this parasite without attentive beekeepers that use chemicals to kill the mites.

“It requires more hands-on time,” says Virginia beekeeper Richard Reid. “It’s good to breed from your own queens that tend to deal with mites really well and are good honey producers. You pick out the ones that have all the good traits and you breed new queens from those. It’s quite easy once you get the hang of it and equipment to put them in to expand and start new colonies.”

Another threat to hives comes from the small hive beetle, which usually invades around June or July. According to Horn Potter, the female beetle will lay eggs throughout the hive. When these eggs develop, they feed off the hive’s pollen and honey, and then defecate, which causes the bees to abandon the hive.

Bee Misconceptions Debunked

- Wasps are not bees, and neither are they pollinators. They are carnivores and some species are very aggressive.

- Only 45 of the 20,000 bee species produce honey.

- Male honey bees do not forage for nectar or pollen, but focus on mating with the queen.

- The lifespan of bees ranges from two to three weeks for male miner bees and four years for honeybee queens.

- Honeybee workers can only sting once. Their stinger is attached to the end of their digestive system and remains in the skin, so using their stinger is fatal.

- Male bees cannot sting and not all female bee species can sting. When bees do sting, it is usually out of self-defense.

The use of pesticides is another major threat to bees. According to the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, an international nonprofit organization, insecticides can be lethal and at the very least affect bees’ foraging and nesting habits.

This is a more pressing problem in areas where the landscape is dominated by industrial-scale agriculture.

“In some areas, like where we are in the mountains … we don’t have any big agribusiness here, and I’m not seeing pesticide use as any kind of problem to speak of,” says Reid. “Bees are sampling their whole area, many thousands of acres, and bringing little pieces of that back to their own hives.”

However, Wilkes of Hive Tracks suggests that the pesticide issue can be minimized by controlling the location of bee yards. He has experience facilitating conversations with beekeepers and pesticide users.

Tammy Horn Potter advises people to consider the hours that they spray pesticides, if they cannot be avoided. Kentucky’s mosquito spraying program, for instance, operates between 8 p.m. and 4 a.m. “That whole idea is to give the product time to dry before pollinators are flying,” she says.

The Xerces Society also suggests limiting the application of pesticides to the target plants to prevent drift.

In addition to pesticides and parasites, sometimes honeybee troubles come from poor nutrition.

“Bees need to have pollen for protein,” says Reid. “They need it for raising young, healthy bees. They also need to have nectar in order to overwinter and create honey. Some years aren’t very conducive to good nutrition, when the weather is hot and rainy, so you end up with deficits that may compromise the bees’ health.”

The Bee Economy

According to Horn Potter, honey bees arrived in the United States with European settlers in the 1600s.

“Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, honey provided a sweetener and was used for its soothing quality in cough syrups,” says Horn Potter. “It’s also antibacterial, so it could help deal with surface wounds. Beeswax was critically important as far as waterproofing boots, coats and candles. ”

The practice of beekeeping as it is known today became widespread on mountain farms by the mid-20th century, according to Timothy Osment, a masters graduate from Western Carolina University.

“This whole industry of growing bees, selling bees has gone through the roof,” says Wilkes. “That, coupled with [the number of] hobbyist beekeepers exploding because everybody’s interested in bees, which is great.”

“There’s a pretty big movement on eating local and knowing where your food comes from,” says Tennessee beekeeper Charlie Parton. “We need to keep that alive and part of that is local honey.”

Local honey is in high demand, according to Parton. “I can never produce enough local honey,” he says. “I lost 50 percent of my bees this winter so this is a rebuilding year for me. So that means people are not going to have enough local product.”

James Wilkes demonstrates how to use HiveTracks, a record-keeping software he created for beekeepers. Photo courtesy of James Wilkes.

Honey’s purported health benefits are also driving demand. “I have numerous people that buy honey from me,” Parton says. “They’ll tell me, ‘My doctor told me to get some local honey to help my allergies.’”

In addition to the widespread belief that local honey can provide immunity to seasonal allergies, honey can also be used to boost energy or as a topical treatment for scalp conditions and wounds, according to a website run by Dr. Joseph Mercola, an osteopathic physician.

Horn Potter believes the Appalachian region has bee-related economic opportunities beyond honey production. She pushes for expanding the queen production industry, which involves growing and selling queens, as well as getting Appalachian beeswax for cosmetics to the rest of the country.

“The cosmetics [industry] won’t touch beeswax from hives in the United States because of how many chemicals can be found inside,” says Horn Potter. “We continue to have to import wax from Africa for our cosmetics industry.”

Proper pesticide management would lead to higher quality wax, Horn Potter says, and is essential for this industry to bloom in Appalachia.

According to Everett Oertel, former apiculturist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the queen-rearing market began in Massachusetts in 1861. In recent decades, developments have been made to produce hybrid and artificially inseminated bees.

With the latest colony losses, “we are always short of queens every single year,” says Horn Potter. “To me, this region would produce a really good quality queen.”

A New Bee-ginning

New beekeepers examine hives as part of

the Appalachian Beekeeping Collective. Photo provided by Appalachian Headwaters.

Atop a vast open field in the mountains of West Virginia, at least 50 beehive boxes mark where new beekeepers are learning the practice as part of the Appalachian Beekeeping Collective.

Appalachian Headwaters is a nonprofit organization founded in 2016 to focus on restoration of mine lands in the region. The Appalachian Beekeeping Collective was created out of this in 2017 as an economic development opportunity for southern West Virginia. The program provides supplies, support and training to low-income and displaced workers, among others.

This year, the program has worked with 35 trainees. According to Kate Asquith, director of programs at Appalachian Headwaters, they hope to add an additional 75 trainee beekeepers in 2019.

The organization is now processing and promoting the collective’s honey to high-demand markets that would otherwise be inaccessible to small-scale beekeepers. This year will be the first time their honey is sold.

“By selling it out of the region and with good marketing, we hope that we’re able to help people get a much larger benefit from their work,” says Asquith. “The next phase of our work is starting to work with people who have skills already and helping them to expand their businesses so we really work with all sorts of beekeepers.”

The honeybee’s decline and inconsistent recovery shows the need for informed beekeepers is growing. Colony losses due to bee health problems can be prevented or recouped with attentive management by beekeepers.

“If you want to get into beekeeping,” says Richard Reid, “join a local club, take a class and have fun.”

Appalachian Bee Legends

In John Parris’ “Mountain Bred,” a book of Appalachian folktales and legends, he dedicates a chapter to the Appalachian folklore surrounding beekeeping. In 1967, Parris spoke with county farm agent Paul Gibson who stated that some believe “if a colony of bees swarm, you’ve got to get out and ring a bell or beat on a dishpan before they’ll settle.”

German and English colonists in the Appalachian region began a practice of “telling the bees,” according to Tammy Horn Potter’s book Bees in America. It is believed that when a beekeeper dies, someone must tell the bees or they will leave or die. In Kentucky, this telling was done through a song.

Parris recounted a similar belief that if the beekeeper dies, the bees will die too, unless they are moved. In 1975, he verified this with Eliza Jane Bradley, a Cherokee, N.C., native who was the recent widow of a master beekeeper. “The Old Man died about 3:30 in the morning,” Bradley recalled. “Right away we sent to Bryson City for the undertaker. And the very next thing, I told one of my boys that the bees would have to be moved. He and another fellow went out — it was still dark and cold — and moved the bees. There was 23 stands. Since then I’ve lost but two … Now, I know, as sure as I’m a-settin’ here, if them bees hadn’t of been moved there wouldn’t be a one out there now. I know what I’m talkin’ about.”

In other Appalachian folklore, the “news bee” appears as an omen, according to history buff Dave Tabler’s Appalachian History website. It is said that if a yellow news bee perches on someone’s finger, it is good luck. On the other hand, a black news bee signifies imminent death.

The species known as the news bee is not technically a bee but a type of fly. The yellowjacket hoverfly –– Milesia virginiensis –– is named for its ability to hover over flowers. It is often mistaken for a hornet because of its aggressive flying and buzzing, but unlike hornets and bees, it only has two wings instead of four.

Remarkable Pollinators

Related Articles

Latest News

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This was very interesting reading I am a new beekeeper I love my bees I am hoping that they do good I try to stay out of my hives but I love to see their work I now have a total of ten hives looking forward to next year hoping to get more