Traditions of Resistance:

Lessons from the struggle for justice in Appalachia

By Molly Moore

In 1964, a 61-year-old Kentucky woman, Ollie “Widow” Combs, sat in front of a bulldozer to halt the strip-mining of the steep land above her home. She spent that Thanksgiving in jail, and a photograph of Combs being hauled away landed on major papers nationwide. Her action drew national attention to the broad form deed, a mineral-sale agreement that gave companies that owned a property’s mineral rights the freedom to destroy the land’s surface in order to reach the coal reserves beneath.

Outraged by the broad form deed, which gave owners of mineral rights precedence over landowners, members of Kentuckians For The Commonwealth successfully pushed for a constitutional amendment against the practice. Photo courtesy of Kentuckians For The Commonwealth, kftc.org

Months later, an 80-year-old Baptist preacher and coffin-maker, Dan Gibson, stood up to the strip-miners who arrived at his stepson’s property in Knott County, Ky. His stepson was serving overseas in the Vietnam War, and Gibson refused to leave the land until he struck a deal with the offending coal company that kept bulldozers off of his stepson’s land.

It took 22 more years of protest, organizing and lobbying before Kentucky courts threw out that interpretation of the broad form deed.

“There has always been resistance in the mountains,” says Stephen Fisher, professor emeritus at Emory and Henry College and editor of “Fighting Back in Appalachia” and “Transforming Places,” two histories of Appalachian justice movements. “It’s taken different formats, but what’s impressive about this resistance is it has come against just incredible obstacles.”

Neighborhood action to regional coalitions

From the hardwood treasures that led to the clear-cutting of nearly all of Appalachia in the early 20th century to the coal reserves that are uncovered by blasting away mountaintops, the abundant environment that gifted regional residents also brought about a “resource curse.” As outside interests capitalized on the extraction and export of Appalachia’s riches, the economic reward rarely reached mountain residents, who often suffered consequences such as contaminated water and poorer hunting and fishing habitats.

Generally, Fisher says, episodes of resistance were driven by people “reacting to attempts to destroy their way of life or break down their community or take away their land.”

History books recount numerous local struggles that reflect the range of threats. In 1982 the community of Brumley Gap, Va., prevailed against a plan from Appalachian Electric Power to drown their valley behind a hydroelectric dam. In 1989, residents of Dayhoit, Ky., whose water was dangerously contaminated with toxic waste from a manufacturing plant, joined together to demand answers and protections from industry as well as state and federal agencies. Also during the 1980s, communities in western North Carolina began denouncing clearcutting — channeling their outrage into the Western North Carolina Alliance’s Cut the Clearcutting campaign, which led to a revision of the long-range plan for the Nantahala and Pisgah national forests in 1994.

Though the history of environmental justice movements in Appalachia is largely a story of citizens fighting one problem at a time, decades of local defiance have also inspired some organizations to address multiple progressive issues and foster the endurance to work on long-term reforms.

Statewide Organizing for Community eMpowerment — formed as Save Our Cumberland Mountains in 1972 to fight strip mining in the area —now has chapters throughout Tennessee addressing issues from nuclear energy to access to healthy food. Similarly, Kentuckians For The Commonwealth began in 1981 as the Kentucky Fair Tax Coalition to reform a tax code that favored coal operators; today the group is concerned with environmental struggles, voting rights and more. Appalachian Voices, which publishes The Appalachian Voice, initially addressed forest restoration and air pollution — now the organization focuses on the environmental and health impacts of mining and burning coal and advocates for energy efficiency and clean energy.

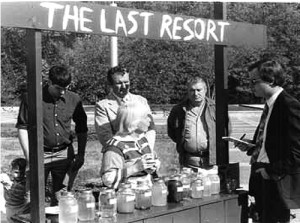

To bring attention to water problems caused by mining, oil and gas drilling and landfills, KFTC members took water samples to Frankfort, set up a “lemonade stand” and offered passersby drinks like Brine Brew. Photo courtesy of Kentuckians For The Commonwealth, kftc.org

Today, these three groups are all members of The Alliance for Appalachia, a coalition of 15 local and regional groups working to end mountaintop removal coal mining and support a sustainable regional economy. This alliance formed in 2006, and while its focus and strategies reflect current challenges and politics, the formation of a coalition to share knowledge and influence is rooted in the past.

One such coalition, the Council of the Southern Mountains, formed in 1912 with a focus on education and community development. The group persevered until 1989, by which time it had expanded its work to include issues such as opposition to strip mining and support for miners’ strikes. It weathered a period of upheaval in the late ‘60s that saw an ideological and organizational split between the council and the Appalachian Volunteers, another group invested in the region’s “war on poverty.”

The Council of the Southern Mountains also overlapped with the Appalachian Alliance, a coalition of grassroots groups that formed in the ‘70s, around the same time that activists were arguing that Appalachia’s poverty stemmed from its colonial relationship to the rest of the country.

“That [viewpoint] sort of tried to demonstrate how we were invaded like the Third World was, in terms of outside interests coming in that took over control of resources and the land and also imposed a culture and maintained that control,” says Fisher. “And that was a very convincing model because you can sit on your porch in the coalfields and see the coal going out. Then seeing your kids go to school with broken-out windows and no healthcare — you could see the resources falling out. And there’s a bit of truth to it.”

Fisher was involved with the Appalachian Land Ownership Task Force, formed in 1979, which trained citizens in six states to visit local courthouses and track down information on landowners and their property tax payments. After delving into the data, he says, researchers were able to clearly document the way outside land ownership and the property tax code correlated with poor roads, healthcare and other services. These findings inspired action — the Kentucky Fair Tax Coalition successfully lobbied to remove the property tax exemption for unmined minerals.

Tracking the Money

Though some lessons from Appalachia’s history are abstract, others are as concrete as cash. Dianne Bady co-founded the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition in 1987 to successfully fight what would have been the world’s largest chemical waste incinerator near Ironton, Ohio. Since then, the organization has undertaken a host of issues, but one of the most enduring lessons the group encountered came during a 12-year campaign to stop pollution problems at an Ashland Oil refinery in Catlettsburg, Ky.

According to Bady, if a citizen had a complaint about the refinery, regulators at the local Ashland air pollution office would investigate and write violations in response. But when those violations reached the state office in Frankfort, they were usually dismissed. Advocates realized how political contributions from Ashland Oil — the largest in Kentucky — were making it nearly impossible for local regulators to enforce the law.

Eventually, after sustained citizen pressure, Ashland Oil was forced to pay a hefty fine and upgrade pollution controls — the company was the first in the nation ordered to install video cameras linked to regulatory offices.

After seeing the power of political contributions in the Ashland Oil episode, Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition added campaign finance reform to its priorities. The organization influenced the passage of several West Virginia campaign finance laws, including one that gives the state’s supreme court candidates a public financing option.

“When we started working on mountaintop removal coal mining, nobody in the state was talking about campaign contributions from the coal industry to politicians,” Bady says. Along with West Virginia Citizen Action Group, the organization researched every state campaign contribution greater than $250, connecting donations to businesses.

Not only did the research reveal what Bady calls “the extreme influence the coal industry had,” it also showed that candidates who received more funding from the industry were more likely to vote in favor of coal interests on contentious state bills.

“We were so proud at the time, when we saw that statewide media began to look for themselves for [information on campaign finance reform] whereas before it wasn’t something anyone was really looking at,” Bady says. “Unfortunately in West Virginia, Kentucky and other states, coal still controls our politicians so it hasn’t been a panacea.”

History Builds a Case

When Cindy Rank reflects on the environmental struggles she’s participated in since stepping up to fight proposed surface mines near her home along West Virginia’s Little Kanawha River in the ’70s, her mind turns to the surface mining and clean water laws passed around the same time that she was getting involved.

Rank, now chair of the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy’s mining committee, says that even though many Appalachian advocates at the time didn’t think those laws went far enough, they have been valuable. She notes that these laws give environmentalists more legal options when it comes to mining than currently exist with issues such as Marcellus Shale natural gas drilling.

It’s not just the legal victories that matter, she says, it’s the opportunities that court cases present to call upon national experts in fields such as flooding or stream health. She cites a 1998 mountaintop removal lawsuit, which led to a 1998-2005 environmental impact statement that in turn “kicked off the avalanche of research” on mountaintop mining.

“It is these studies then that have carried the message to media and the country and regulatory agencies on a level that we as citizens and citizen monitors can only begin to penetrate,” Rank writes. “We offer compelling first-hand experience and stories and offer anecdotal evidence, where concerted peer reviewed studies by nationally recognized folks lend credence to what every person living below or near mountaintop removal experience, see, feel, hear, smell, witness every day.”

Nearly 50 years after Ollie “Widow” Combs marched up the slope behind her home to put her body in front of the approaching bulldozers, the struggle for environmental justice in Appalachia continues. Large companies seeking coal and gas reserves still hold great political influence, and the region’s people still grapple with the “resource curse” of the mountains.

Yet the abundance that can inspire greed is part of a natural landscape that also inspires pride, independence and community traditions of resistance. In this issue, we devote a special section to stories of Appalachian resistance — to environmental and economic abuses and to attempts to bury the region’s proud history. And in the December/January issue of The Appalachian Voice, we will hear from the visionaries and innovators that are setting the tone for the region’s next chapter.

Appalachian Voices Milestones

From mountain communities to the halls of the nation’s capitol, Appalachian Voices, the publisher of The Appalachian Voice, has played a role in the region’s justice movement.

1996: The Appalachian Voice was created by Harvard Ayers and first published by the Sierra Club’s Southern Appalachian Highlands EcoRegion Task Force.

1997: Appalachian Voices organization was founded by Ayers.

1998: Began community organizing work in southern West Virginia.

2000-2002: Brought together 12 North Carolina groups for a campaign that succeeded in passing the Clean Smokestacks Act, then one of the nation’s strongest air pollution laws.

2003: First Appalachian Treasures Tour marked start of Appalachian Voices’ national campaign to end mountaintop removal coal mining.

2004: Helped form Christians for the Mountains, a non-denominational religious campaign founded on the idea of caring for creation.

2006: Joined with 12 other organizations to form The Alliance for Appalachia, and held the inaugural citizen End Mountaintop Removal Week in Washington, D.C., and congressional briefing on mountaintop removal. Launched iLoveMountains.org.

2007: Established an office in Washington, D.C., and helped found the Wise Energy for Virginia Coalition. Also launched the “Appalachian Mountaintop Removal” layer in Google Earth and the online “My Connection” tool.

2008: Helped to launch an energy efficiency campaign in Virginia and campaigned with Wise Energy for Virginia partners to achieve dramatic reductions in permitted emissions for a proposed coal plant in Wise County.

2009: Worked with Sens. Lamar Alexander and Ben Cardin to introduce the Appalachia Restoration Act and hold the first Senate hearings on mountaintop removal coal mining. Launched campaign with the Wise Energy for Virginia Coalition that successfully opposed the largest proposed coal-fired power plant in Virginia.

2010: Launched Appalachian Water Watch program in Kentucky to train citizens how to monitor water quality in streams adjacent to mountaintop removal mines; program is later expanded to Virginia. Documented more than 30,000 Clean Water Act violations from two coal companies in Kentucky; initiated legal actions against the companies that led to unprecedented fines.

2011: Launched the Red, White & Water campaign to educate the public about negative health effects of coal ash and coal-fired power pollution.

2012: Promoted the Scenic Vistas Protection Act, a bill to ban mountaintop removal in Tennessee that reaches floor of state Senate.

2013: Launched an Energy Savings for Appalachia program to help mountain communities save electricity through energy efficiency financing programs. Partnered with SkyTruth to create Appalachian Water Watch pollution alert system. Worked with Wise Energy for Virginia coalition partners to launch New Power for the Old Dominion campaign for clean energy in the state.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *