Front Porch Blog

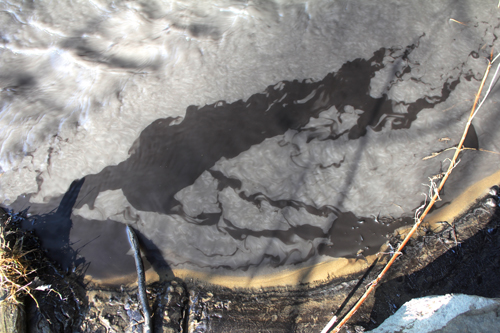

Coal slurry turns Fields Creek dark gray. The lighter brown sediment just barely visible shows a more normal sediment color.

Appalachian Water Watch has received the first set of results from our sampling at the site of the Patriot Coal slurry spill, which occurred sometime in the early morning of Feb. 11 on Fields Creek in Kanawha County, W.Va.

We responded to the scene that afternoon and were able to collect grab samples from multiple locations along the creek, from an upstream site just outside the entrance to the coal preparation plant where the spill originated, to a downstream location just before Fields Creek enters the Kanawha River.

As with most coal-related spills, there are some obvious contaminants associated with coal that should be measured. Many heavy metals, such as manganese and iron, are commonly found in rock layers around coal seams. Other nonmetal elements, such as selenium, are also common in some coal seams. We typically test for a set of heavy metals and other elements, including manganese, iron and selenium, as well as other serious toxins like arsenic.

At a coal prep plant, coal is shipped in from surrounding mines and “washed” to separate it from other materials before it is shipped to buyers. Chemical frothers, like 4-methycyclohexane methanol (MCHM), which spilled into the Kanawha River earlier this year, are used in the separation process. Multiple types of chemicals may be used in different activities around a prep plant. Once the chemicals are no longer needed, they are often disposed of in giant slurry ponds near the prep plant facility. This makes it difficult to know which compounds to test for when slurry spills into a creek.

Google Earth image of the Patriot slurry ponds.

In the case of the Patriot spill, it was difficult to obtain information about what chemicals might have been used at the facility. Initial reports indicated that MCHM might be involved in this spill. Later reports indicated that Patriot had stopped using MCHM in January and was instead using polypropylene glycol.

We decided to test for MCHM in Fields Creek for two reasons: First, if MCHM had been used at the Patriot facility at some point, it seems highly likely that discarded MCHM would be present in the coal slurry, even if it were no longer being used for processing. Second, we smelled the distinct sweet smell of the chemical at several points along Fields Creek.

We have received test results confirming that MCHM was present in Fields Creek on Feb. 11. The results indicated 4-MCHM at 46 parts per billion. This amount is a relatively small quantity, but given how little is know about the impacts of the chemical on humans or aquatic life, it is not currently possible to say whether this amount would have any negative impacts. Thankfully, the nearest groundwater intake is 75 miles downstream and the nearest surface water intake is 115 miles downstream of the spill site, so it is highly unlikely that MCHM from this spill would impact drinking water. We did not find propylene glycol present in our grab samples.

We have also received results for total suspended solids, which indicate the amount of sediment and other undissolved materials in the water column. The first two results were 94 mg/L near the prep plant entrance and 260 mg/L downstream near the Kanawha River. These samples were taken on the evening of Feb. 11, after the spill had been stopped at the prep plant. The upstream level was likely lower than the downstream sample since the spill material had already been washed further downstream.

To put these numbers in perspective, the Clean Water Act National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit for this facility allows Patriot to discharge a maximum of 70 mg/L for total suspended solids on any given day, and an average of not more than 35 mg/L over the course of a month. Clearly this spill was in violation of the these standards, at the very least. We are still waiting on results from heavy metal testing and will make them available as soon as possible.

Nobody needed the results of laboratory testing to know that the slurry spill was detrimental to Fields Creek. The dark gray water was indication enough that toxins were present in the water and that aquatic life would likely be suffocated by fine sediments. As the nearby houses with cheerful yards and children’s toys reminded us, the potential exists for long-term impacts on nearby residents. No one is drinking directly from Fields Creek, but how many other ways might the residents come in contact with those contaminants?

Though the amount of MCHM found in Fields Creek was small and unlikely to impact drinking water, it is still a very important finding. What it shows is that companies responsible for these spills are allowed to withhold information and avoid responsibility for knowing the details of the risks they pose to surrounding residents and the environment. After the MCHM spill from a chemical storage facility on the Elk River, Freedom Industries waited two weeks before disclosing that a second chemical, PPH, had been present in the tank that had leaked.

During the Patriot slurry spill, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) believed MCHM might be involved. Presumably Patriot told the DEP this. Later, the DEP stated the smell of MCHM was from a tanker truck removing MCHM from the prep plant. Given our test results, the MCHM smell was clearly not from a tanker truck. Regardless of who was feeding misinformation to whom, it seems ludicrous that a state regulatory agency seems to have so little power to make a coal company operating in West Virginia provide accurate and timely information about a spill that occurs from their facility.

But maybe given the state Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management Director Jimmy Gianato’s statement that the spill “turned out to be much of nothing,” we shouldn’t be so surprised at state agency ineffectiveness in West Virginia. Apparently 100,000 gallons of coal slurry spilling directly into a tributary of the Kanawha River is just not a big deal in West Virginia these days. Something tells me the citizens of West Virginia feel otherwise.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *