Front Porch Blog

By B. McInturff

With additional reporting by Willie Dodson

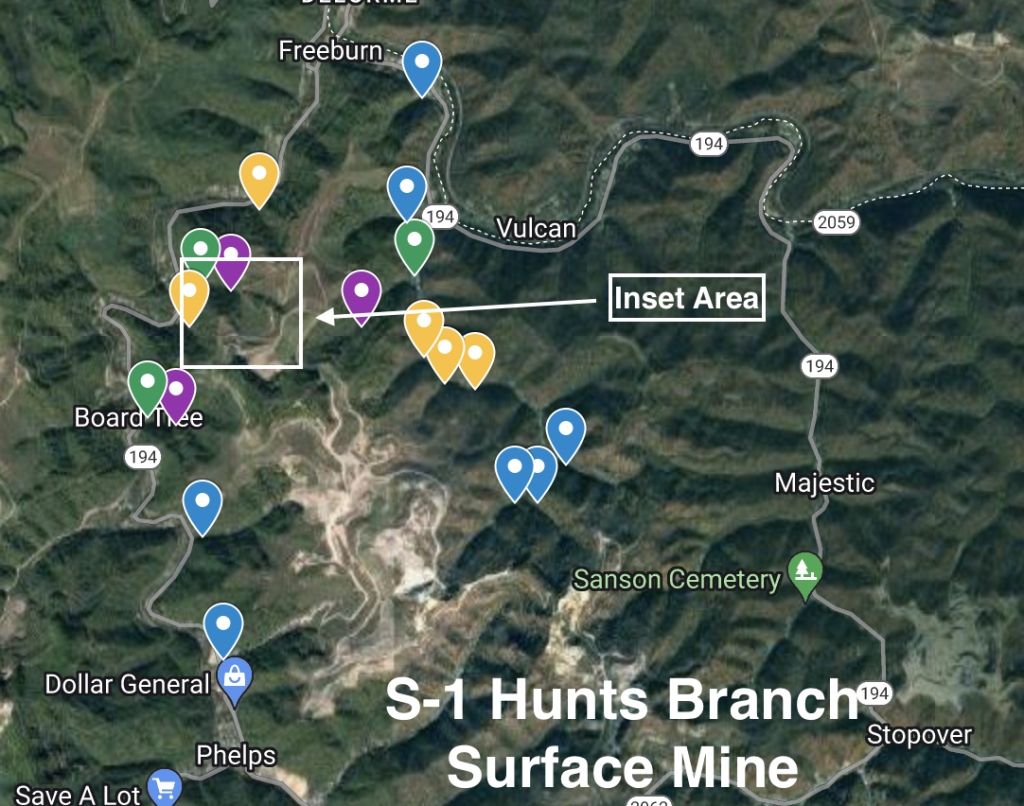

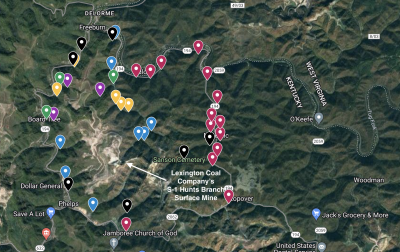

In late summer of 2022, Appalachian Voices discovered selenium, a common pollutant associated with coal mining, in high concentrations in certain streams in the Big Sandy River watershed in Pike County, Kentucky. These waterways receive runoff from the S-1 Hunts Branch Surface Mine, a nearly 2,000-acre mountaintop removal coal mine operated by Lexington Coal Company.

An Appalachian Voices investigation found that the Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet had wrongly classified disturbed areas of the mine as being reclaimed, meaning regulators mistakenly listed these areas as being cleaned up after mining. This allowed Lexington Coal to ignore the presence of selenium discharging into streams.

Over many months of independent investigation and engagement with state and federal agencies, Appalachian Voices’ work successfully compelled state regulators to impose a legal requirement in 2023 that Lexington Coal monitor discharge points from the S-1 Hunts Branch Mine for selenium. But new evidence obtained by Appalachian Voices suggests the company is failing to meet these requirements.

Selenium has caused grotesque deformities from s-curved spines and double-headed larvae to fish with both eyes on the same side of their heads. These fish (above) were caught at Belews Lake, N.C., which is adjacent to a Duke Energy coal-fired power plant. Photo by Dr. Dennis Lemly

Under the mine’s state-issued Clean Water Act permit, Lexington Coal Company must monitor runoff for selenium, unless that runoff drains from a “reclaimed” area of the mine, as regulations presuppose that “reclaimed” areas do not produce as many pollutants as active mining areas. Some of the areas classified as “reclaimed” on the S-1 Hunts Branch Mine appeared to include large unvegetated or sparsely vegetated areas in satellite imagery, prompting Appalachian Voices Central Appalachian Field Coordinator Willie Dodson to review reclamation compliance records for the mine. This research turned up citations EEC issued against the mine for failing to properly restore the original contour to one portion of the mine discharging runoff into Church Branch. Church Branch was one of five streams where Dodson and then-intern Jennifer Gilliam had documented elevated levels of selenium.

These revelations compelled Appalachian Voices to file a complaint with the EEC in December 2022, alleging incorrect classification of “reclamation areas” and elevated discharges of selenium from the mine into Big Sandy River tributaries. The complaint also included requests for permission to conduct a citizen inspection of the mine during which Appalachian Voices personnel could collect water samples and photographs.

EEC granted Appalachian Voices’ request to conduct a citizens’ inspection, accompanied by representatives from the state, but the agency refused to allow us to take water samples or photos of the affected areas. On Jan. 4, 2023, EEC representatives met Gilliam, another Appalachian Voices intern named Jay Callahan and Central Appalachian Environmental Scientist Matt Hepler for the inspection.

EEC personnel, accompanied by Appalachian Voices, collecting discharge from S-1 Hunts Branch Mine, January 2023. Photo by EEC

As Kentucky regulators had failed to address the evidence Appalachian Voices brought regarding the improper reclamation designation and the presence of selenium, our team then appealed to federal regulators to get involved.

On May 22, 2023, Hepler submitted a request to the federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, asking that they exercise their “10-Day Notice” authority to intervene. Under law, most states have the responsibility to regulate coal mining within their borders, but the OSMRE has oversight authority. This includes the authority for OSMRE to conduct its own investigations and give state regulators, like the EEC, ten days to address any problems uncovered by OSMRE.

Upon investigation, OSMRE found that several supposedly reclaimed areas did not in fact qualify as such, and directed EEC to revise the mine’s state-issued Clean Water Act permit mandating selenium monitoring for all unreclaimed areas.

Google Maps satellite image of S-1 Hunts Branch Surface Mine

Portion of S-1 Hunts Branch Surface Mine at issue in Appalachian Voices’ 2022 complaint

This change was a win for Appalachian Voices’ efforts to enforce mining regulations, but the true impact on water quality in Church Branch and downstream waterways depends on Lexington Coal Company not only monitoring, but actually controlling selenium runoff.

Under the Clean Water Act, a consistent concentration at or above 5 parts per billion of selenium discharging into a public waterway would normally constitute a violation. But in Kentucky, this concentration only triggers another environmental monitoring requirement — that coal companies collect downstream fish to be analyzed for selenium. Only if the fish tissue contains a certain amount of selenium do Kentucky regulators issue a violation.

Appalachian Voices submitted an open records request to EEC in February 2024 for documentation of Lexington Coal’s compliance with the new selenium monitoring requirements for S-1 Hunts Branch. The agency’s response confirmed that selenium is in fact discharging into Church Branch above the 5 ppb threshold, but that Lexington Coal has not submitted the required fish tissue analysis. On March 27, EEC issued a violation against the company for failing to submit required water monitoring data, giving the company until April 26 to provide the required data.

In addition to the issues regarding reclamation standards and the presence of selenium, Gilliam and Dodson’s initial complaint also objected to the fact that the mine’s surface mining permit did not include a Protection and Enhancement Plan for the Big Sandy crayfish. This is a document required of mines that discharge runoff into, or within 12 miles upstream of, designated habitat for any threatened or endangered aquatic species. The Big Sandy crayfish was designated as threatened in 2016, having lost over 60% of its original habitat due to coal mining and other factors.

Big Sandy crayfish photo by Guenter Schuster. This image is available for media use

EEC did not directly address this issue in their response to our complaint. The mine’s updated Clean Water Act permit does include a note emphasizing that any new discharge points would have to obtain individual permits, due to the presence of the Big Sandy crayfish in neighboring waterways. But a review of public records also found that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service notified EEC on Sept. 29, 2023, that S-1 Hunts Branch is among a group of mines that it determined does not need Protection and Enhancement Plans for this species. Appalachian Voices does not agree with this judgment, and is currently in litigation against FWS and OSMRE over the matter.

—

B. McInturff is an environmental educator, a freelance writer and a volunteer with Appalachian Voices from West Virginia.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment