Front Porch Blog

By Meredith Maiken  Meredith Maiken served as Appalachian Voices Mining Policy intern for spring and summer 2021. Meredith is a student at Appalachian State University, majoring in Environmental Studies and minoring in Community and Regional Planning. She grew up in Western North Carolina and aims to spend her career working towards sustainable solutions specific to rural areas such as those found in Appalachia.

Meredith Maiken served as Appalachian Voices Mining Policy intern for spring and summer 2021. Meredith is a student at Appalachian State University, majoring in Environmental Studies and minoring in Community and Regional Planning. She grew up in Western North Carolina and aims to spend her career working towards sustainable solutions specific to rural areas such as those found in Appalachia.

The coal industry is declining. According to a report from Appalachian Voices released in July, the industry is leaving behind thousands of acres of mined lands in various states of environmental destruction, ranging from eroding soil to polluted waterways across Eastern mining states.

This poses a variety of risks to local communities and the environment. Reclaiming these areas is an expensive task that has been on the horizon for decades. Under the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (SMCRA), coal companies are required to have a plan to finance mine cleanup.

The default plan for covering reclamation is that the company financing mining operations also finances remediating the mine site. States require bonding to ensure there is money available for reclamation in scenarios where the company doesn’t or can’t complete reclamation. As more mining companies file for bankruptcy, states are increasingly relying on reclamation bonds for mine cleanup.

Bonds are secured for either individual permits, or for multiple permits in the form of a bond pool. The amount of money necessary for individual permit bonds is based on estimates of reclamation costs by the state that are often inaccurate or don’t adequately consider what must be done to return the land and water to a healthy state, especially in the long-term. Multiple companies, but not all, participate in state bond pools. The collective funds are available for these mines if companies abandon their reclamation responsibilities. But these bond pools were not designed to withstand the circumstances we see today, where many companies in the same pool may be declaring bankruptcy.

Learn more

Join us Aug. 19 at noon for a webinar about the differences between historical abandoned mine lands and modern day functionally-abandoned mines, what resources exist to tackle these problems, and what you can do to ensure all of these mines are cleaned up.

Register here.

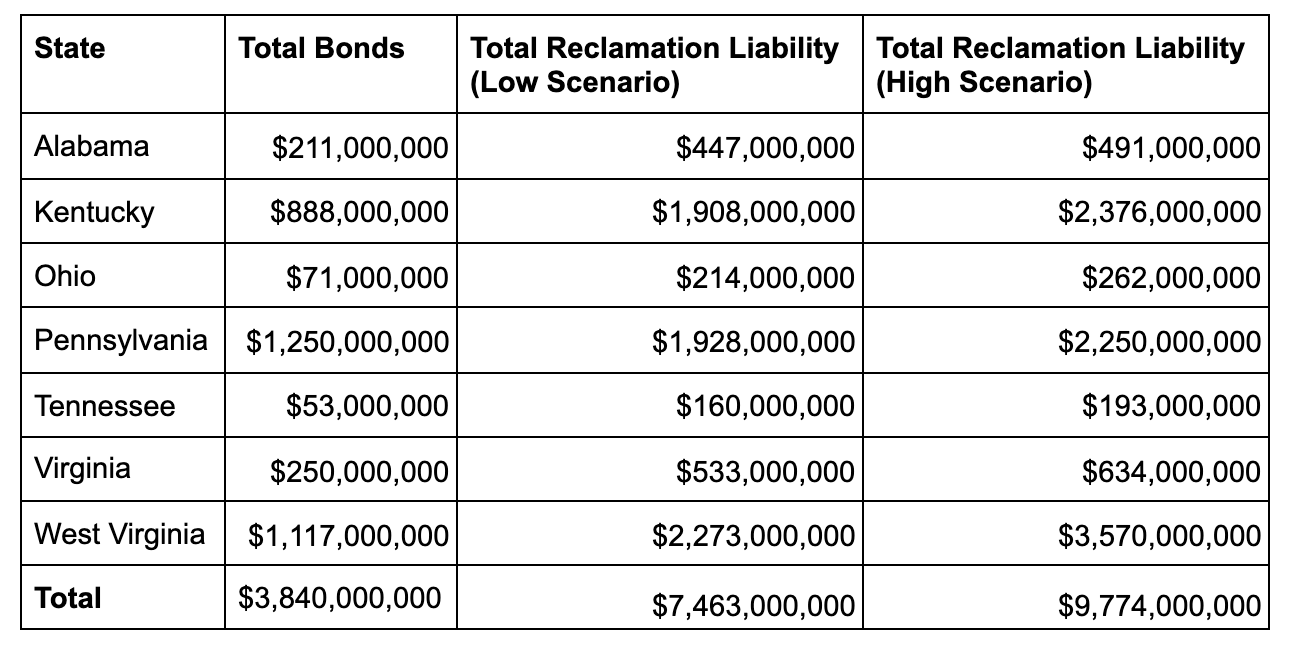

Bonding methods and amounts vary widely from state to state but overall, the amount of these bonds is insufficient to cover outstanding reclamation costs. To better understand the inadequacies of bonding and the need for additional funding and reform, Appalachian Voices collected publicly available data from state agencies to calculate a total outstanding amount of unreclaimed minelands and an estimated cost of reclamation.

These estimates of total mine reclamation needed at modern-era mines are based on publicly available data collected by Appalachian Voices. We included all bond types in the total for each state, except in Virginia, where we did not include self-bonds because of the uncertainty in whether the state will be able to collect those bonds

State agencies don’t track detailed reclamation needs or costs at individual mines, making the depth of the situation hard to understand. Out of the seven Eastern coal mining states, Ohio is the only state that evaluates individual permits for reclamation needs. Individual assessment of sites is necessary for accurately estimating reclamation liability given how widely reclamation costs can vary depending on the type of environmental damage.

The report determined that 426,000 acres of mined land have been partially reclaimed and 207,000 acres are unreclaimed, for an estimated total of 633,000 acres in need of some degree of reclamation. Remediating these sites will cost an estimated $7.5 to $9.8 billion dollars. Not all of these reclamation costs will be covered by bond funds. Some companies will take on the cost themselves, but given the reality of unpredictability and decline of the industry this can’t be counted on.

Comparison of Available Bonds and Total Reclamation Liability

The total amount of available bonds across these Eastern coal mining states amounts to $3.8 billion dollars, falling significantly short of what is needed to ensure that there is a backstop available to cover reclamation across the region. And those bonds are only available to the specific permit or state pool that they were established for, so that $3.8 billion is not equally available across all of the acres that need it.

There are many large, individual coal companies that could leave states’ bond pools empty if they fail to pay for reclamation. One company, A&G Coal Corporation in Virginia, still has 20 self-bonded permits in place — meaning that instead of providing actual cash to back up those bonds, they only promised to provide the cash — and 19 of these permits also participate in Virginia’s $10 billion bond pool. The company’s self bonds amount to $24 million and surety bonds to $5.5 million. In 2016, the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy (DMME) estimated the outstanding reclamation cost at A&G’s mines to be $134 million dollars, far exceeding the state’s $10 billion bond pool.

Little has happened at these permits. In six out the last ten years, there has been no coal produced at the permits and, despite the mines’ inactivity, little to no reclamation has taken place in the last four years. If this inactivity continues, A&G could leave behind land with a $94 million price tag for excessive reclamation costs. It’s possible this number could be even higher if the state department is unable to collect the self-bond amounts from the company. If this is the case, the number could jump to $118 million. At that point the burden would ultimately fall on Virginia taxpayers unless action is taken for more funding. Similar consequences could be felt across all states if enough reclamation funding isn’t secured.

Outstanding Mined Land Reclamation Across Eastern States

This graph represents the total outstanding reclamation needed at current mines that are held by coal companies and under an active SMCRA permit. We have categorized the acreage as unreclaimed and partially reclaimed, where unreclaimed land has had mining activity and no record of significant reclamation, and partially reclaimed land has some record of reclamation progress.

Not taking action on these areas has implications for the climate as well. The report covers this along with other consequences of delaying reclamation in this report. When southeastern forests of the United States were in good health they served as a carbon sink, absorbing more carbon from the atmosphere than they released. But if damaged acreage is not returned to its carbon sequestering potential and these trends continue, the area could become a carbon source by 2025. Land fully reclaimed with native forests has the potential to sequester 3.6 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year. This would be equivalent to removing 770,000 passenger vehicles from the road.

The report puts the real human implications of these modern mines in need of reclamation into context with key economic indicators of the area. Counties with unreclaimed mine sites experience higher rates of poverty and unemployment compared to the national average.

The report makes several policy recommendations that state and federal agencies can take to address reclamation in the region. First and foremost, it would be helpful for states to keep track of how much reclamation is needed by monitoring reclamation liability on a permit-by-permit basis. This information is important for determining accurate bond amounts.

Where there are shortfalls in reclamation bonds at mines already abandoned by coal companies, the federal government should consider providing supplemental funding for mine reclamation. But the report stresses that a program like this should only fund reclamation at mines where the bond has been forfeited and is not adequate for reclamation, and where the regulatory authority has made every effort to recover additional money from all liable parties. If structured this way, such a program would not act as a coal company bailout, as SMCRA includes repercussions for coal companies that abandon permits and forfeit reclamation bonds.

Jumpstarting reclamation projects would provide the opportunity for additional jobs in these areas that have experienced economic distress from the decline of the coal industry. The report estimates that between 23,000 and 45,000 job-years could be created by completing reclamation across the seven states (one job-year is the equivalent of one full-time job for one year).

The report makes clear that Central Appalachia may be facing a new wave of abandoned mines as more companies declare bankruptcy and desert their cleanup responsibilities. But it’s not too late to take action. While coal companies are still profiting, state and federal regulators need to use every available tool to hold them accountable for reclaiming their mines. State and federal agencies need to take this problem seriously and develop solutions to ensure that as the coal industry continues to wind down, communities are not saddled with the aftermath.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *