The Rules of the Solar Game

Nothing is more free than the sun and the wind, right?

The answer is not as clear-cut as one might think, and is different from state to state and even within the same state, as utilities often set their own renewable energy policies.

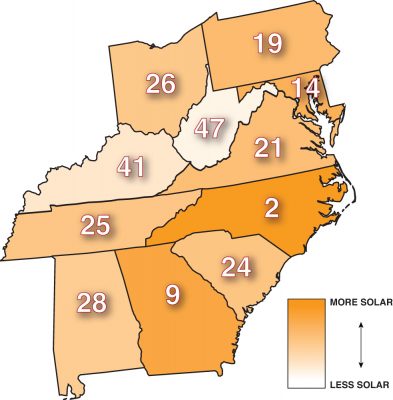

Map of installed solar by state according to 2016 data from the Solar Energy Industries Association. Graphic by Jimmy Davidson

The cost of both residential and utility-scale solar has fallen greatly in recent years and continues to decline. But renewable energy is still relatively young, and utilities large and small are often reluctant to adjust their established business models to accommodate significant investments in the technology.

To incentivize the switch to clean power, the federal government, individual states, investor-owned utilities, electric cooperatives and local governments have adopted a wide variety of policies. Some county or state rules prevent homeowners associations from restricting solar in neighborhoods. Other regulations limit the amount that a home renewable energy system contributes to property tax assessments, while still others provide tax incentives for companies that create jobs in fields like solar. And that’s just the beginning.

Combined, these policies have a palpable impact on the ability of an individual or a state to transition from fossil fuels to renewables.

This is evident in Central and Southern Appalachia, a region that is home to both North Carolina, the state with the second-highest amount of installed solar capacity in the nation, and to 47th-place West Virginia, with plenty of variation in between.

What sets states like North Carolina and ninth-place Georgia apart? It comes down to rules and regulations that help make solar a smart investment.

Harnessing Solar in Appalachia

- Intro: Harnessing Solar

- Seeking Opportunities in Solar

- Rules of the Solar Game: Policies can create a level playing field or stack the deck

- Former Coal Company Town Integrates Energy Efficiency and Solar

- College Solar Vehicle Teams Drive Sustainable Transport Forward in Region

- Unique Solar Applications

Solar Policy 101

Though there are a wide range of solar policies, only one — federal tax incentives — is available nationwide. All residential and commercial solar installations are eligible for a 30 percent tax credit until 2019, at which point the credit will begin declining until 2022, when the residential tax credit expires and the commercial credit holds steady at 10 percent.

Renewable energy portfolio standards are another crucial driver of solar growth, according to Georgetown University’s Solar Institute. These state policies typically require electric utilities to generate a certain percentage of their power from renewable sources or solar in particular.

A 2007 law passed in North Carolina, for instance, requires that investor-owned utilities — namely Duke Energy — generate 12.5 percent of their electricity from renewable sources by 2021, with 0.2 percent of that coming from solar. The law also mandates that electric cooperatives and municipal utilities acquire 10 percent of their power from clean sources by 2018. In recent years, repeated efforts to overturn the renewable standards in the North Carolina legislature were unsuccessful.

Maryland has a similar rule, but requires 25 percent renewable energy by 2020 with 2.5 percent from solar. In fact, renewable standards are required in 29 states, including Ohio and Pennsylvania. Virginia and South Carolina are among the eight states with voluntary goals, while Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee and West Virginia have no such goal or mandate.

Much of these statewide goals is being achieved by large commercial and utility-scale solar arrays. But rooftop solar is making a dent, too. In 2006, less than one percent of all new electricity generation in the United States came from small-scale solar, according to data compiled by the Institute for Local Self Reliance, an advocacy organization. That figure grew to 12.4 percent by 2013 and was at 16 percent for the first three quarters of 2016.

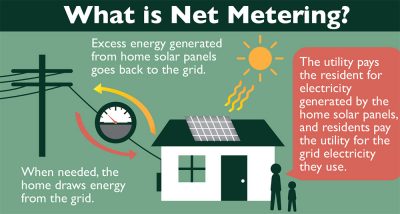

Solar advocates often attribute the nationwide surge in small, distributed solar power in part to net metering, a policy that gives homeowners who want to stay connected to the grid an opportunity to generate solar power. Depending on how a state or utility’s net metering policy is structured, it can also help make residential solar a sound financial investment.

Mechanics of Net Metering

With net metering, residents can install solar panels on their property and directly use the electricity generated by those panels. When their solar panels produce more power than the home needs, a bi-directional electricity meter allows excess energy to flow back to the grid, and the utility pays the homeowner for that energy at an agreed-upon rate. And if the home needs more energy than the home system is currently providing, that bi-directional meter flows the other way and residents can pay the utility to use energy from the grid.

This arrangement makes it possible for homeowners to generate even just a portion of their electricity from solar, and allows residents to rely on the grid for nighttime power.

Net metering is mandatory in 38 states, including most of Appalachia. The region’s only exceptions are in Georgia, where utilities are allowed but not required to offer net metering, and areas served by the Tennessee Valley Authority, a federal utility that serves nearly all of Tennessee and portions of six surrounding states.

The growth of net metering, however, has been met with backlash from some utilities and industry associations. In 2012, David Owens, the executive vice president of the Edison Electric Institute, an influential utility interest group, gave a presentation that discussed how small-scale, distributed solar and the policies that support it — including renewable energy portfolio standards and net metering — represented a growing threat to utility profits.

In the years since, legislation to block net metering or make it more expensive for homeowners has been introduced in states across the country. This is particularly true in the Southeast, where utilities and solar advocates continue to spar over how net metering systems should be structured.

The central area of dispute involves the rates that residents pay for the electricity they use versus the rates that utilities pay residents for excess electricity generated by their home systems. Sometimes those rates are the same, and sometimes homeowners are paid less for the energy they produce than what they use from the grid. And some utilities also charge participants in net metering programs an added monthly fee.

In Virginia, utilities are required to offer customers 12 months of “retail rate” net metering, where the utility pays the same price for a home’s excess electricity as the homeowner pays per kilowatt-hour from the grid. But after 12 months, the utility can negotiate a different agreement with the homeowner.

“This will likely be for a price that represents the utility’s “avoided cost” of about 4.5 cents, rather than the retail rate, which for homeowners is about 12 cents,” Ivy Main, renewable energy chair for the Virginia Sierra Club, wrote in a June 2017 blog post. “This effectively stops most people from installing larger systems than they can use themselves.”

According to Lauren Bowen, a North Carolina attorney at nonprofit legal firm Southern Environmental Law Center, solar power — whether generated at commercial or residential scale — allows utilities and society at large to avoid the costs of air and water pollution and associated cleanup.

“In addition to the environmental benefits of solar power you also have benefits to the grid and customers of independent renewable companies companies — benefits like generating electricity closer to where it’s needed, less electricity lost over the distribution transmission lines as its going from the point of generation to where it is needed,” Bowen says. “Rooftop solar is particularly great for this.”

Those benefits, solar advocates argue, should also be reflected in the amount utilities pay residents for their home-generated electricity.

Utilities and industry associations like Edison Electric Institute, on the other hand, have argued that customers with their own solar power buy less electricity from the grid and therefore are not paying an adequate amount to cover ongoing grid maintenance. Such groups have pushed for adding new monthly fees or renegotiating net metering arrangements so that power companies can pay homeowners less.

Changing Rates?

“We see these net-metering battles popping up across the country, and it’s really important that at this stage of relatively low solar penetration that those net-metering policies are protected,” says Alissa Jean Schafer, solar communications and policy manager with the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, an advocacy organization.

In February 2017, a bill was introduced in Kentucky that would have grandfathered in existing net metering customers but opened the door for utilities to negotiate less favorable rates for new accounts. The bill did not advance during the legislative session, but could be reintroduced next year.

Environmental advocates also expect a proposal to surface during the commonwealth’s upcoming General Assembly session that would alter Virginia’s current policy.

“Any changes to Virginia’s net metering system that remove barriers to participation or reduce excess extra charges are welcomed, as long as they are not coupled with changes that lengthen the payback period for the average residential solar array,” says Peter Anderson, Virginia program manager with Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper. “Without net metering, people would be faced with the challenges of going ‘off the grid’ in order to incorporate any home solar, and they would be deprived of the key revenue stream that helps pay off the cost of their systems.”

In North Carolina, the statute only requires investor-owned utilities — namely Duke Energy — to offer net metering. But some of the state’s member-owned electric cooperatives also offer the program.

Blue Ridge Energy serves roughly 70,000 co-op members in the state’s northwestern corner. In 2014 and 2015, when North Carolina offered a 35 percent state tax credit for investment in solar, Blue Ridge was signing up about 20 solar homes each year, according to Jason Lingle, the cooperative’s manager of energy solutions.

In 2015, the state credit tax expired and Blue Ridge Energy introduced two new revised rate models. After that, the number of new rooftop solar systems per year dropped to between 10 and 15. The first plan has a fixed charge of $36 per month, up from $24, and pays the homeowner roughly 6.8 cents per kilowatt-hour for the excess energy they generate. The second plan offers a lower fixed charge — just $2.91 per month — but offers just 5 cents per kilowatt-hour instead.

Beginning in November 2016, residential and small commercial customers were offered the option to enroll in Blue Ridge’s new community solar program, where subscribers purchase energy produced from the cooperative’s four 368-panel solar arrays. Customers can buy the output from up to 10 solar panels for a monthly fee, and opt to be reimbursed using one of the two rate models.

Whenever a co-op member expresses interest in rooftop or community solar, Lingle talks with them about the amount of electricity they typically use to determine which model would benefit them.

“One method is strictly going to be as more of a solar participant, so you’re actually not going to have any savings from it if you’re a low user of electricity,” Lingle says. “But a higher user of electricity [is] going to save money from the program. And actually we have most people kind of in that average kilowatt-hour range and above actually saving money with the program.”

Following the North Carolina legislature’s passage of energy-related House Bill 589 over the summer, the two-thirds of the state served by Duke Energy may also see changes to their net metering program. The new law requires public utilities to file for revised net metering rates with the state utilities commission.

The bill addresses a wide array of solar policies, including changing how commercial-scale solar developers procure contracts with Duke Energy. Before, solar developers were guaranteed a standard contract with Duke for certain types of solar systems, but now they will undergo a competitive bidding process to contract with Duke. The law also commits Duke to purchasing 2.6 gigawatts of solar power through that bidding process over 45 months and establishes a residential solar leasing program.

The bill was met with mixed reaction from environmental groups. Jim Warren, executive director of climate justice organization NC WARN, expressed concerned that Duke “would attack rooftop solar by adding more fees on customers and lowering net metering payments.” Rory McIlmoil of Appalachian Voices pointed out that since municipal utilities and electric cooperatives are exempt from the law, “most of the state’s rural areas are once again being left behind when it comes to the benefits of solar energy development.”

Lauren Bowen of Southern Environmental Law Center noted that much of the law’s impact will depend on how the state utilities commission enacts the details of the legislation. “The key is to make sure the implementation of the bill continues to make North Carolina a clean energy leader going forward,” she says.

While solar’s environmental and climate benefits may energize much of the public, the technology typically needs to make financial sense in order for a homeowner to take the leap.

“That’s part of our conversation with the average member — you know, are you doing solar for the environmental reasons or the economical reasons?,” Lingle with Blue Ridge Electric says. “From a lot of our conversations, people are still doing it for a lot of economical reasons.” And that means there’s still a need for sound policies that help residents harness the sun’s power.

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment