Front Porch Blog

The Perfect Solution to North Carolina’s Coal Ash Crisis

There’s been a lot of controversy about how North Carolina will deal with its coal ash crisis ever since Duke Energy spilled nearly 40,000 tons of toxic coal ash into the Dan River last February. Shortly after the spill, legislative leaders voiced icy determination to pass a bill that would force Duke to quickly clean up its toxic coal ash lagoons and protect the state’s rivers and groundwater from further insults.

The hope that all this tough talk would translate into bold action began to fade last month, however, when the state Senate passed a bill that would allow Duke to use “cap in place” techniques at some (possibly most) of the state’s coal ash lagoons rather than requiring Duke to use the kind of modern landfills that are required for disposing of household garbage.

Then, what little hope remained appeared to be lost in early July when the House passed a bill that would let Duke off the hook on the timelines for even these meager clean-up efforts. Fortunately, the Senate unanimously rejected the House’s anemic bill earlier this week, meaning the differences between the bills will now have to be worked out in a conference committee next week.

But the question remains, how could these tough-talking legislators have been convinced to pursue such a myopic solution to the state’s coal ash woes?

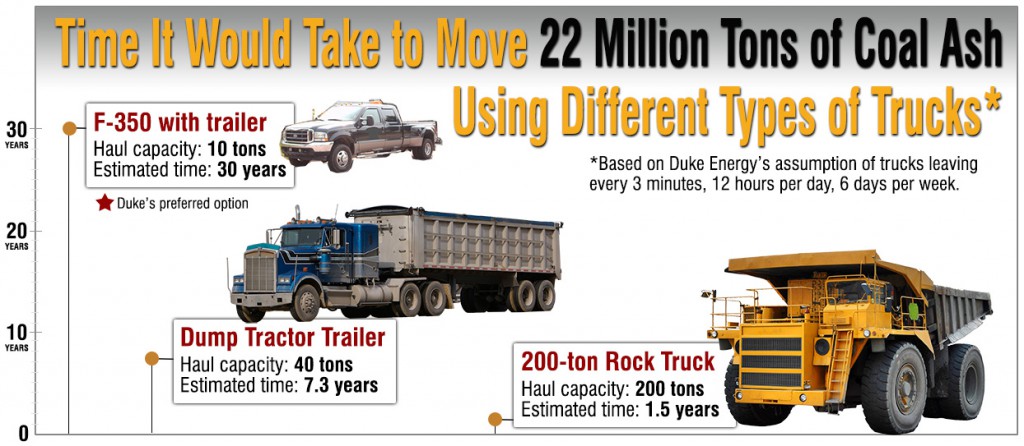

The answer is that Duke’s lobbyists managed to scare legislators by convincing them that it wouldn’t be feasible to move all this coal ash to landfills on a 5, 10, even 15-year timeframe. The centerpiece of their argument is a remarkable analysis [PDF-page 15 in particular] by Duke’s engineers that claims it would take 30 years to move 22 million tons of coal ash at their Marshall Steam Station if a dump truck were to leave every three minutes, 12 hours per day, six days per week.

From the moment it was made public, though, this analysis seemed a little fishy. Duke consumes 4 or 5 million tons of coal every year at the Marshall plant, but it can’t even move 1 million tons per year of coal ash to a landfill? A back of the envelope calculation indicates it would take only a quarter that much time to move the volume of material Duke was talking about with a U-Haul!

So we took a closer look at Duke’s analysis and discovered an astonishing fact: it is based on the assumption that they could only haul 10 tons of coal ash per load, which is roughly the weight you could pull in a trailer with a Ford F-350 pickup. A light bulb went on in my head… what if Duke used a BIGGER truck to haul all that coal ash?

What if, for instance, the company bought a few of those 200-ton rock trucks that mountaintop removal coal companies use to dump waste and debris into stream valleys in Appalachia in order to supply Duke with coal? With that kind of hauling capacity, they could move all the coal ash in the biggest lagoons in the state in a mere 18 months.

Now to be fair, you can’t drive a 200-ton truck on a public road. That means that in the rare cases where there is no place on site to create a landfill it would take longer than 18 months. But even assuming Duke’s lobbyists can’t get an exception to the state’s 40-ton weight limit for light-traffic roads (as apple growers, Christmas tree farmers and many less influential industries in Raleigh have already done), it could still be done three or four times faster than if they were to wear out a Ford F350 pulling one 10-ton trailer at a time.

And just in case you’re concerned about where Duke might possibly acquire such an advanced piece of hardware, rest assured that we checked online and… wow… there are an awful lot of those trucks for sale right here in the great state of North Carolina.

So the final problem to solve is how to pay for Duke’s new dump truck. Now, you might think a $2 million investment in a big old rock truck shouldn’t be a problem for the largest electric utility in the nation, which cleared nearly $3 billion in profits last year. But that’s because you simply don’t understand the mindset of a Duke Energy executive.

The way a Duke executive feels about spending money on hippy-dippy stuff like protecting rivers and drinking water from toxic pollution is a lot like how you or I feel about spending our tax dollars bailing out Wall Street firms whose malfeasance recently crashed the economy.

So here’s our solution: we’ve set up a grassroots fundraising campaign on Crowdrise so that all y’all can help us raise a cool $2 million to buy Duke Energy a shiny new dump truck and, at the same time, ease legislators’ minds about passing a bill that will hold Duke accountable for safely disposing of millions of tons of toxic coal ash.

You’re also invited to a celebration at Duke’s headquarters in Charlotte later this summer where we’ll present them with a check for all of the proceeds. In the unlikely event that Duke refuses the money then we’ll use it to pay for well water testing in communities living near coal ash dumps in North Carolina and to support local groups who are trying to force Duke to clean up the coal ash problem in their neighborhood.

It’s a big win for everyone! Donate today.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Matt, I guess I was envisioning the per-existing open pit mines that are being abandoned at the end of their “life”. Using existing “best practices” for landfills, someone should be able to come up with a method to seal these pits and then use them as a landfill for the ash. Not a perfect solution but preferable to leaving where it is now.

That’s a reasonable thought process, Gary, and would certainly solve the problem of moving large quantities of waste. Unfortunately, minefilling of coal ash has caused terrible water quality problems in some communities in Appalachia where it has occurred. The problem is that when you put coal ash into abandoned mines, it is put directly in contact with aquifers for which people often rely on for drinking water. But keep up the creative thinking – Lord knows there’s not nearly enough of that going on over at Duke Energy.

Seems to me that most of these plants are served by rail.

It also seems that most of the rail cars leave empty going back for more coal.

It also appears that every open coal mine is a deep hole that could be converted at some point in it’s life into a sealed landfill for the very byproducts of the coal that left the hole… Shouldn’t take but one or two sites to solve the problem.