Ecological Impacts of Mountaintop Removal

The Appalachian region is home to one of the oldest and most biologically diverse mountain systems on the continent. Tragically, mountaintop removal mining has already destroyed more than 500 mountains encompassing more than 1 million acres of Central and Southern Appalachia.

After the coal companies blast apart the mountaintops, they dump the rubble into neighboring valleys, where lie the headwaters of streams and rivers, like the Kanawha, Clinch, and Big Sandy. The exposed rock leaches heavy metals and other toxics that pose enormous health threats to the region’s plants and animals — and people.

Water

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that mountaintop removal “valley fills” are responsible for burying more than 2,000 miles of vital Appalachian headwater streams, and poisoning many more. As a result, water downstream of mountaintop removal mines has significantly higher levels of sulfate and selenium, and increases in electrical conductivity, a measure of heavy metals. These changes in water quality can directly kill aquatic species, or disrupt their life cycles so severely that populations dwindle, or even disappear (see below).

For more than a decade, dumping of mountaintop removal waste into streams has occurred under a loophole created during the Bush Administration. In 2002, a new definition reclassified mining waste as permissible “fill material” under section 404 of the Clean Water Act. Under the change, the coal industry drastically accelerated mountaintop removal mining, with grave consequences. In the words of U.S. District Judge Charles H. Haden II:

“If there is any life form that cannot acclimate to life deep in a rubble pile, it is eliminated. No effect on related environmental values is more adverse than obliteration. Under a valley fill, the water quantity of the stream becomes zero. Because there is no stream, there is no water quality.”

Proposed legislation called the Clean Water Protection Act would have reversed this definition and restored the full protection of the Clean Water Act to Appalachia’s streams. Appalachian Voices, along with our partners in The Alliance for Appalachia and others, strongly advocated for passage of this critical bill for several years, and while more than 200 congressional allies supported the effort over the years, it was ultimately unsuccessful due to industry lobbying.

Forests

The EPA estimates that by 2012, mountaintop removal had destroyed 1.4 million acres of Appalachian forest. After the topsoil and upper portions of a mountain’s rock have been removed, the remaining soil is incapable of producing native hardwood forest.

Because the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act of 1977 does not require coal companies to reforest the land as part their post-mining reclamation work, the previously lush terrain is usually replaced by flat fields of non-native grasses where the traditional Appalachian forests take much longer to grow back, if they ever do (EPA). This means not only lost wildlife habitat, but also the steady disappearance of a forest system that naturally captures and holds carbon dioxide, one of the greenhouse gases responsible for climate change, what scientists call a “carbon sink.” One study argues that rampant deforestation in southern Appalachia could convert the region from a net carbon sink to a net carbon source by 2025 to 2033.

Biodiversity

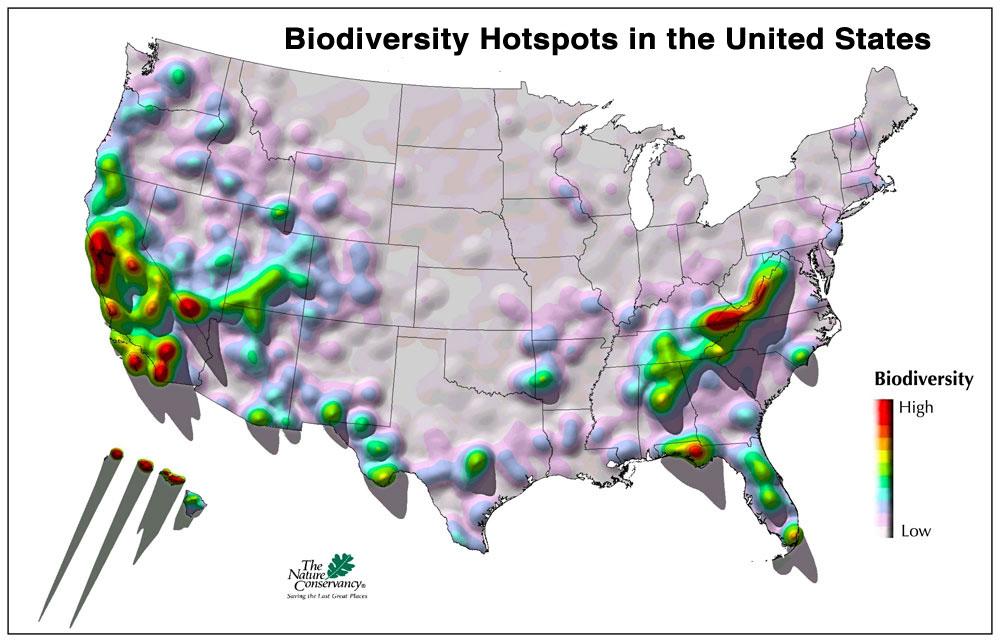

Central Appalachia is a special place in America. The region, including southwest Virginia, southern West Virginia, eastern Kentucky and northeastern Tennessee, provides habitat to thousands of plant and animal species, many of which are found only here. According to the World Wildlife Fund, Appalachia contains “one of the most diverse assemblages of plants and animals found in the world’s temperate deciduous forests.” It’s also the heart of mountaintop removal mining activities.

Birds

Bird species that rely on mature forest habitats are numerous in Appalachia. According to the American Bird Conservancy, the Kentucky warbler, Worm-eating warbler, Wood thrush, Louisiana waterthrush, and Cerulean warbler are all impacted by mountaintop removal operations. Cerulean warblers are in particular danger, as their populations have decreased by almost 70% since 1966. Appalachia’s mixed hardwood cove forests and shaded streams are key to the survival of this species — but this habitat is rapidly disappearing.

Fish

As living indicators of water quality, Appalachian fish have experienced habitat degradation, declining populations, and increasing cases of developmental abnormalities in waters downstream of mountaintop removal sites.

A 2014 study released by the U.S. Geological Survey demonstrates that fish populations downstream of mountaintop removal mining operations were reduced by two-thirds between 1999 and 2011. The authors of the study point to the loss of suitable habitat due to valley fills and mining pollution as an explanation. In addition, high selenium concentrations contribute to the increasing scarcity and lower quality of the fish’s prey.

Dangerously high levels of conductivity and selenium have also been discovered in correlation with developmental abnormalities among West Virginia fish located downstream of mountaintop removal sites.

Other aquatic species

The impacts of mountaintop removal on aquatic species on the lower tier of the food chain further threaten the rich biodiversity of Central Appalachia. In 2009, Doug Wood, a biologist for West Virginia’s Department of Environmental Protection, expressed concern over evidence that an entire order of mayfly had vanished from streams below valley fills, writing that such a loss is “equivalent to the loss of all primates (including humans) from a given area.”

Native salamander populations surrounding mountaintop removal valley fills also have been found either completely absent or significantly reduced in number, sometimes even replaced by reptiles on reclaimed mine sites. This displacement reflects the area’s transition from a lush habitat to a dry environment uninhabitable by amphibians due to mountaintop removal.