Shape-Note Singing

Letcher County, Ky., is home to the annual East Kentucky Double All-Day Singing weekend. In 2019, participants sang from “The Sacred Harp” on Saturday and from “Sacred Selections” on Sunday. Singers also visited local restaurants, churches and community centers. Photo by Malcolm J. Wilson

As a tradition practiced since 1801, shape-note singing is one of the oldest forms of music in the United States. Rooted in the rural South, it thrived during the 19th century as a form of education and socializing. Today, it persists in Appalachia and across the world.

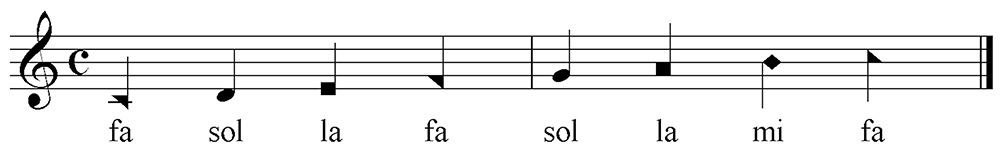

Shape-note singing, sometimes referred to as Sacred Harp, originated from an Italian 11th-century system that uses syllables like “fa,” “sol,” and “la” to teach musical scales. Instead of writing music with classic oval-shaped note heads, the system uses different shapes — a triangle for “fa,” an oval for “sol” and so on — to indicate each note’s pitch. This helps singers easily sight-read and learn new pieces of music.

Triangles, ovals, rectangles and diamonds are used in the four-note “fa so la” scale. The most popular shape-note songbooks, “The Sacred Harp” (1844) and “The Christian Harmony” (1867), used four- and seven-note scales respectively.

At a shape-note singing, the room is divided into four groups that face inward to form a hollow square. Shape-note singing uses no instruments. Each section is assigned a different melodic line, and the leader stands in the middle. First, everyone learns their parts by singing the note names, like “fa,” “sol,” “la,” and “mi,” instead of words. After singing the notes, the four parts join and sing the words together. The harmonies layer and fill the room with a sound singers describe as unique and powerful.

According to Ben Fink, co-founder of the annual weekend-long East Kentucky Double All-Day Singing, the Appalachian region is a key part of the musical tradition’s history.

“It basically got pushed further and further down the Appalachian chain until it took root and never left in the southernmost mountains,” he explains. “The Appalachian mountains, in the broad sense, have been a home and location for this music for a long time.”

Fink states that the current practice of shape-note singing is not an act of preservation. Rather, it is the practice of something alive, well, and meaningful to its community.

“We’re not standing outside of it and trying to preserve it. We’re inside of it, and we’re doing it,” he says. “It’s a living tradition.”

Though many shape-note singers receive the tradition from older generations, others discover it on their own. Classical music was the family practice for Randall Webber of Louisville, Ky., but after coming across a copy of the songbook “Southern Harmony” about 12 years ago, he started composing shape-note songs. Groups in the region have sung his pieces for the past decade, and a few of his songs are being considered for the upcoming edition of the songbook “The Sacred Harp.”

“Of course it’s fun having other people and players sing what you’ve written,” Webber says. “You get to meet people. It’s sort of like an extended family.”

For Fink, that family is constantly growing. After moving to Kentucky in 2015, he and a few others began organizing regular singings throughout Letcher County. In 2017, they hosted the first annual East Kentucky Double All-Day Singing weekend. During the event, singings are held throughout the day on Saturday and Sunday. The weekend also includes cultural events, such as dinner and music at the Carcassonne Square Dance. Singers also attend the annual communion service at Defeated Creek Old Regular Baptist Church and participate in a lined-out singing. Still practiced in Kentucky, this centuries-old tradition features a group repeating lines first sung by the leader.

“The fundamental virtue of shape-note singing is hospitality,” Fink says. “We like to provide as much first-hand opportunity to get to know the people and places here as we can.”

In 2019, the weekend was attended by more than 50 singers representing 13 states and two other countries. The 2020 annual singing weekend is scheduled from Aug. 8 to 9.

Shape-note singing also offers a way for students to connect to Appalachian culture. In the Bluegrass, Old Time, and Country Music Studies program at Eastern Tennessee State University, participants in a new shape-note singing course learn about both music theory and regional culture through experience.

Lecturer Kalia Yeagle was eager to direct the course, and she remarks that it has been a highlight of the semester.

“This class is a cool way for my students to dig into a tradition that has some sort of relevance to this area,” Yeagle says. “In teaching ourselves to shape-note sing, we’re inherently learning about cultural heritage.”

Though shape-note singing is prevalent in East Tennessee, Yeagle explains that there was not a concrete opportunity for most students to learn about it. However, increased student interest in the tradition inspired the music studies program to design a course for students to learn and sing shape notes together. Some days, they open the classroom and invite others to join their singings.

Shape-note singing also acts as a metaphor for unity, according to University of Kentucky Professor Emeritus Ronald Pen. He taught Appalachian Music for 30 years and founded the John Jacob Niles Center for American Music. He also helped establish the Appalachian Association of Sacred Harp Singers in Lexington, Ky.

“It’s a way of bringing four different, very independent melodic lines together,” Pen explains. “What we’re really talking about is musical harmony creating social harmony.”

He explains that though shape-note singing was designed to teach people how to sing, it also served as a way for communities to socialize. Today, technology can interfere with how humans connect, but shape-note gatherings still allow people to join together and actively participate in music-making.

“When you come together to sing shape notes, you’re sharing something with people in a real, active way,” he says. “Music that springs from the soil, that’s tied closest to the earth at hand, has the most power to move us. And Sacred Harp is that music.”

To learn more about the East Kentucky Double All-Day Singing weekend, contact Ben Fink at (612) 840-0141 or ben.fink@gmail.com.

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

[…] According to Appalachian Voices, participants in shape-note singing sit in a “hollow square…. The leader stands in the center, guiding the group through the powerful, haunting melodies. This communal style of singing fosters a strong sense of community and shared purpose among the participants. […]

Are there any shape note sings in Northern Illinois or Southern Wisconsin??

Are there any shape note singings scheduled for 2022 or 2023

hi- i am trying to find out about sings in the US between august 16-19- in the appalachians- dont know where to find out- any tips? thanks

coming over from the UK!