The Problem with Monopoly Utilities

When it comes to electricity options, the average person doesn’t have much power.

Most utilities enjoy energy monopolies over an area, whether they are a huge investor-owned company or a rural electric cooperative. This makes it essentially impossible for most people to choose where their power comes from, even if they disagree with their electricity provider’s decisions such as their handling of coal ash or investment in fracked gas instead of renewable energy.

Are these utilities serving the public’s best interest in the 21st century? Yes and no, says Jim Lazar, a senior advisor with the Regulatory Assistance Project, a global organization that works to advance clean energy.

“[Utilities] certainly provide essential services: electricity, natural gas, water, sewer and other public utility services,” says Lazar. “They mostly do it at a reasonable cost, and they mostly do it with pretty high reliability. So in that sense, the answer is yes. But are they doing the best possible job for consumers? No. Are they doing the best possible job for the environment? No. They have mixed incentives, and mixed obligations.”

According to Lazar, these mixed incentives stem from the fact that investor-owned utilities like Duke Energy are beholden to their shareholders’ interests, not the interests of ratepayers. “That’s the way corporations work; they can’t put any interests ahead of the owners of the company,” he says.

Duke Energy Carolinas’ W.S. Lee natural gas station in Anderson County, S.C., began service in April 2018. Over the next 15 years, the utility calls for about 3,600 megawatts of additional natural gas-fired electricity generation. Photo courtesy of Duke Energy

Investor-owned utilities serve the majority of the country’s electricity customers. In nearly all states, these utilities are regulated by state public utility commissions appointed by elected officials, which gives the public some oversight over these large companies. Publicly owned electric cooperatives serve many customers in rural areas, and they are overseen by member-elected boards. Utilities owned by federal, state or city governments also play a part.

Most states allow investor-owned utilities to have monopolies on energy, and the states have extensive power to regulate them. The choices utilities and regulators make, such as whether to focus on conventional fossil fuel infrastructure or renewable energy, can have massive ramifications on the environment, types of available jobs and monthly electric bills.

High electricity costs hit underprivileged households the hardest. Low-income, rural households spend 9 percent of their annual income on energy, compared to the national average of 3.3 percent, according to a July 2018 report by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, a nonprofit policy organization. Nearly one in three American households struggled to meet their energy needs in 2015, according to a September U.S. Energy Information Administration report.

The prices that regulated, investor-owned utilities like Duke Energy can charge customers are set by state agencies. These prices cover capital investments and operating costs, plus a profit, or “rate-of-return,” on capital investments. One of the factors that goes into determining the price, or “rate,” is how much utilities spend on projects that the regulator deems prudent — meaning that the more power plants utilities build, the more money they can receive and use to generate profits. This incentivizes utilities to spend as much money as possible on new projects, whether or not those projects are of value to the public.

This growth-driven model worked in the 19th and 20th centuries as the nation was building the current grid, but times have changed. Energy demand has fallen, partially due to energy efficiency; residential electricity sales per person in 2016 were down 7 percent from their peak in 2010, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Additionally, the world is becoming more aware of the climate dangers posed by fossil fuels — NASA states that 2017 was the second hottest year on record after 2016.

The price to install solar has fallen by more than 70 percent since 2010, according to the trade group Solar Energy Industries Association. Smart technology has led consumers to expect more from their phones, homes, televisions and now the grid. For example, demand-response systems allow ratepayers to tell their electric utility to cycle their water heaters off during peak electricity usage hours in exchange for a lower utility bill.

These changes point to a more renewable, flexible and consumer-focused energy system. But big industries can be slow to change, especially without prodding from regulators.

“We’ve spent 120 years in this industry forecasting consumption and scheduling supply, and when we are burning fossil fuels we can do that,” says Lazar. “As we move away from fossil fuels to wind and solar and batteries and demand-response, we’re going to be spending more time forecasting supply and scheduling the demand to fit that. That’s a pretty dramatic change, and most utilities are not ready for it — and the regulatory framework in which they operate is really not ready for it either.”

Climate Consequences

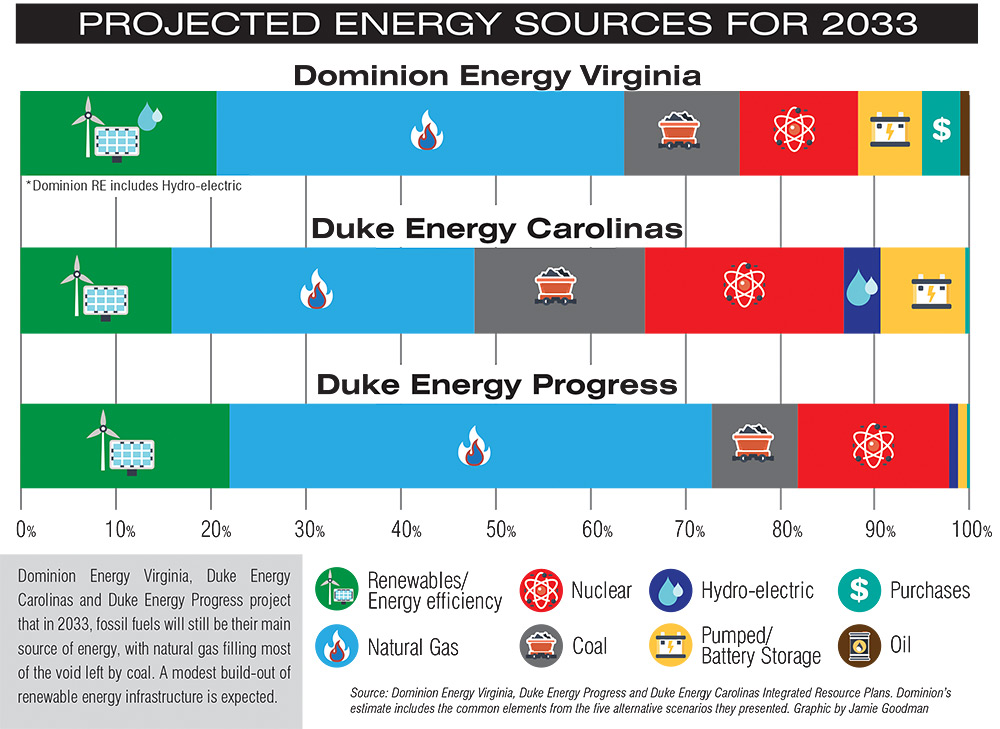

In September, Duke Energy Progress and Duke Energy Carolinas filed plans with the North Carolina Utilities Commission listing what energy sources they expect to invest in between 2019 and 2033.

“As we retire old coal, in most cases we will replace that with natural gas,” Duke spokesman Randy Wheeless told Utility Dive. “Going forward, Duke Energy’s new capacity additions will be renewables (solar, battery and pumped storage) and natural gas.”

During that time period, the Duke subsidiaries plan to add 3,663 megawatts of solar power. The two subsidiaries are also planning a massive buildout of natural gas infrastructure — 9,596 megawatts by 2033 — which earned criticism from David Rogers with the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign.

“While it’s good that Duke is starting to realize that investing in clean energy sources makes more sense than burning coal, this plan doesn’t go nearly far enough,” Rogers said in a press release. “Burning coal until 2048 is hardly a ‘carbon constrained’ scenario, as their filing claims, nor is a massive expansion of plants that burn fracked gas, which, over its first 20 years in the atmosphere, [releases methane that] is 87 times more potent for trapping heat than carbon dioxide.”

Dominion Energy Virginia — a subsidiary of Dominion Energy, the fourth largest utility in the nation as of April 2017 — plans to build at least 4,720 megawatts of new solar capacity by 2033, and is developing a community solar pilot program in Virginia (click here to read more). However, the utility also plans to build at least eight new gas-fired plants totaling 3,664 megawatts in the same time period.

Jim Warren, executive director of NC WARN, a nonprofit clean energy advocacy organization, states that utility companies are furthering the climate crisis by building more fracked gas infrastructure.

“They have been acting as a key force in moving humanity toward that climate tipping point, especially through the greatly expanded use of fracked gas over the last several years,” says Warren.

He also notes that climate change helped make September’s Hurricane Florence so devastating. Before the storm hit, scientists from Stony Brook University, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the National Center for Atmospheric Research were projecting that human-caused climate change increased Florence’s rainfall by more than 50 percent. Post-storm analysis has yet to be released.

“We know what to do to take the best chance to avert runaway climate chaos; and yet major corporations, Duke Energy being one of the worst, are actively trying to thwart that approach,” says Warren.

Both Dominion and Duke have invested billions in the 600-mile Atlantic Coast Pipeline, which would transport fracked gas across West Virginia, Virginia and North Carolina. The project continues to attract widespread opposition (click here to read more).

Rory McIlmoil, energy savings program manager for nonprofit organization Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper, calls Duke and Dominion’s investment in the pipeline “just another example of them wanting to make as much profit as possible and expand their control over the energy market.”

Tomorrow’s Grid

Smart meters like this allow homeowners greater control over their electricity usage. Photo courtesy of Talbott/NIST

Utilities across the country are attempting to adapt with a wave of “grid modernization” investments — a catch-all term for projects like smart meters that advance the electric grid. In the second quarter of 2018 alone, utilities in more than 40 states took steps toward grid modernization, according to an August report by the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center, a publicly funded organization based out of North Carolina State University.

Grid modernization projects are attractive to investor-owned utilities because, if they are approved by regulators, the costs of those projects plus a guaranteed rate-of-return can be recouped through customer charges. However, the definition of grid modernization is vague. Many utilities like Duke and Dominion are attempting to use the term to justify earning a profit at ratepayers’ expense on ventures that could be seen as standard operations and maintenance — which the utilities have traditionally not been allowed to profit from.

According to McIlmoil, electric utilities across the nation are pursuing grid modernization to make up for flat or declining revenue due to residential solar and greater energy efficiency.

“They’re looking for a new way to invest money that will allow them to generate a profit — and the new, big and shiny investment is grid modernization,” he says.

In March, the Virginia General Assembly passed a controversial law that made substantial changes to electricity rate structure and energy policy. The Dominion Energy-backed law, which stands to massively benefit the utility, was opposed by some lawmakers and citizen groups, including Appalachian Voices.

Among other things, the law gives Dominion the ability to charge its customers billions of dollars to bury power lines underground, and strips the State Corporation Commission’s ability to determine if the project is “reasonable and prudent.” The law also allows Dominion to reinvest any and all customer overcharges into grid modernization, renewable energy or energy efficiency projects instead of issuing refunds.

“We’re consigning our consumers to going forward in a future in which they will be permanently overpaying for electricity,” said Virginia State Sen. Chap Petersen during the General Assembly’s debate in February 2018. “I don’t believe in giving anybody a blank check.”

This year, Duke Energy Carolinas proposed their own grid modernization effort called Power/Forward. In June, the N.C. Utilities Commission struck down the $7.8 billion ratepayer cost increase.

A Duke Energy lineman. Parts of Duke and Dominion Energy’s grid modernization plans, which earn the utilities a rate-of-return, include projects such as burying power lines underground. Critics state that those projects are standard maintenance and should not be profited from. Photo courtesy of Duke Energy

McIlmoil states that some of the initiatives Duke included in Power/Forward were standard operations and maintenance costs like replacing aging infrastructure or burying lines underground — something that Duke should not be able to profit from. “Very few of the investments that were included in Duke’s narrative actually reflect improving the grid in a way that prepares the grid for a clean energy future,” he says.

Power/Forward earned criticism from legislators, the North Carolina Attorney General and public interest advocates including Appalachian Voices. According to Gudrun Thompson, a senior attorney with nonprofit law firm Southern Environmental Law Center who litigated against Duke’s proposal, Power/Forward put too much burden on the utility’s residential ratepayers.

“Duke Energy proposed to bill residential customers over $5.6 billion over the next 10 years for Power/Forward (72 percent of the Company’s planned $7.8 billion spend),” Thompson wrote in an email. “But only 3.5 percent of the potential cost savings from Power/Forward ($59 million out of a total of $1.61 billion) would accrue to residential households.”

Thompson notes that one reason regulators rejected Duke’s proposal was the utility’s failure to show public need.

“Duke just did not do a good job of explaining what this Power/Forward initiative is, what the projects actually consist of,” beyond a general argument for grid reliability, Thompson says. She adds, Duke “couldn’t show that there was actually any kind of worsening trend of reliability.”

Duke is considering taking legislative steps in 2019 for the authority to add a “rider,” or temporary extra fee on electric bills, to pay for grid modernization, according to the Charlotte Business Journal.

“We have talked about our strategic priority on grid [modernization] for some time and described that as being a parallel process between the regulatory and the legislative arena,” Duke CEO Lynn Good told the publication in August.

Until then, the utility plans to hold a number of technical workshops on why grid modernization is necessary.

“There are certainly some ways that the grid really does need to be modernized to allow more clean energy onto the grid, and I think there’s room for common ground on that issue,” says Thompson. “I’m hopeful that the series of stakeholder workshops will result in an improved Power/Forward initiative that all stakeholders can agree on.”

Uncooperative Cooperatives

Rural electric cooperatives provide electricity to 56 percent of the nation’s landmass, according to the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, which represents the country’s 900-plus electric cooperatives. The members who pay for power in each electric co-op are also the owners of the cooperative, which is chartered as a nonprofit organization. These member-owners elect board members who oversee the cooperative’s day-to-day operations.

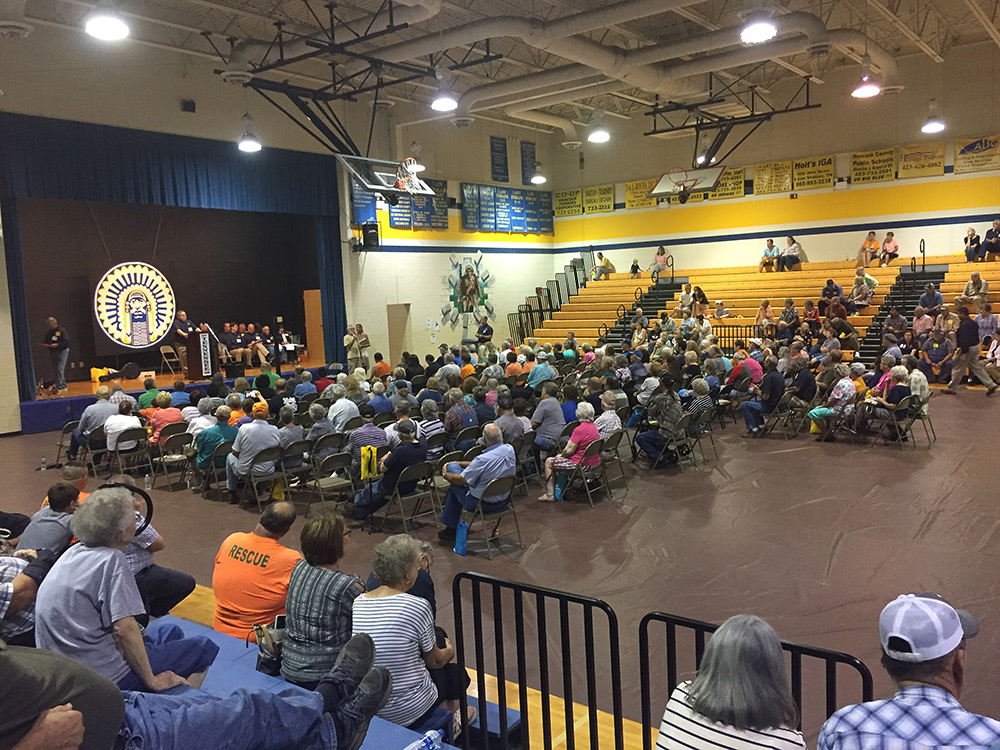

Powell Valley Electric Cooperative’s annual meeting took place on Sept. 15 in Sneedville, Tenn. More than 1,200 member-owners stood in the hot sun for hours to vote for the board of directors, the second-highest number of voters in recent history. Voter turnout was driven in part by PVEC Member Voices, a citizens’ group advocating for reform measures such as open monthly board meetings. Pictured, around 300 people vote on co-op policies. Photo by Brianna Knisley

Since there’s typically little to no state oversight for electric cooperatives, member-owner involvement in the process is critical to holding the co-op accountable for their policies.

Pat Hurley, who has consulted for utility companies for more than 30 years all over the globe, is currently a member-owner of Powell Valley Electric Cooperative in Northeast Tennessee. He says that while the electric cooperative model may sound good on paper, it doesn’t always work.

“For that to work, the owners — whether it’s the public at large or whether it’s directly by the customers — have to pay attention and have to exercise their responsibility in that structure to elect good people to represent them, to speak up when there are policy changes,” says Hurley.

Nationwide, voter turnout for electric co-op board elections is minuscule; 72 percent of electric cooperatives have less than 10 percent average voter turnout, according to a 2016 report by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a nonprofit organization and advocacy group.

And since electric co-ops generally don’t have to report to state or federal regulators in the same way that large investor-owned utilities do, there’s often not public access to cost-of-service analyses to determine the fairness of rates and what the co-op invests in.

“That gets you into the ironic situation where, sometimes, cooperative utilities kind of start doing whatever they want to do,” says Hurley.

Often, as in Powell Valley Electric’s case, small voter turnout at the annual membership meeting is exacerbated by a lack of transparency on the board’s part. Powell Valley member-owners were just granted permission to attend the monthly board meetings without prior request this summer, largely due to the efforts of PVEC Member Voices, a group that has partnered with Appalachian Voices and is aiming to reform the electric cooperative.

However, meeting minutes are still not publicly available, and a bylaw amendment proposed by PVEC Member Voices to ensure a permanent right to open board meetings was blocked from being voted on until summer 2019. Additionally, while prior request is not required to attend meetings, it is needed before speaking at meetings.

“They have these elections every year, and you may or may not have ever even heard of these [board representatives],” says Hurley. “You don’t have any idea of how they’ve been performing because you haven’t been able to watch them or see them individually and what they’re doing, what kinds of questions they’ve asked, what objections they’ve done or anything else.”

This can contribute to another endemic problem of co-ops: long-term board incumbencies.

“There’s no turnover, so it becomes like a little club,” says Hurley. “You don’t have anybody else coming in and looking over their shoulder.”

Related: Seeking Cooperative Change

Hurley states that over 15 years, only four members of Powell Valley’s nine board members have changed. Of those four, three were relatives of previous board members.

“As the board president in Powell Valley said a few months ago when they asked about the nominating process, he said ‘the board selects the nominating committee, and the nominating committee selects the board,’” says Hurley. “In all but a very, very few instances, the nominating committee will nominate the incumbent board members, and there is no other consideration. … [Member-owners] are faced with a slate of the incumbents, and no other alternatives.”

More than 1,000 Powell Valley Electric member-owners waited outside to vote the the co-op’s board election. Photo by Brianna Knisley.

Problems like these are not unique to one electric cooperative. Member-owners are not allowed to attend monthly board meetings for Blue Ridge Energy, an electric cooperative in Western North Carolina. Meeting minutes are also not provided to the public. The cooperative’s policy restricts public comments at their annual meetings to 15 minutes with a maximum of one minute per person.

Member-owners of French Broad Electric Membership Corp. in Western North Carolina are also not allowed to attend monthly board meetings, nor are meeting minutes provided to the public.

But if enough people show up to vote, change can happen. In central South Carolina, more than 1,500 member-owners of Tri-County Electric Cooperative voted out the entire board in August after it was revealed that the part-time board was paying itself more than triple the national average plus benefits, according to The State.

“It may take years, but [member-owners] have to come out and vote,” says Hurley. “They have to pay attention to what the cooperative is doing — and if they don’t like what the cooperative is doing, they have to get new candidates in there, whether it’s by petition or somehow through the nominating process. It seems rather simple, but they just have to pay attention to start with.”

Most electric co-ops are intrinsically linked to large utility companies. According to the Institute for Local Self-Reliance report, 65 to 70 percent of power distributed by electric co-ops is supplied by outside power providers — so the foundation for setting electricity rates is affected by where cooperatives get their power from.

This also affects what type of power co-ops use. For instance, Blue Ridge Energy is contractually obligated to buy most of their power from Duke Energy. In their power-purchase contracts, Blue Ridge has a two-megawatt cap on how much “demand-response,” or technology that reduces grid usage, they can utilize. Since solar power is viewed as a type of demand-response technology, this limits how much solar the co-op can purchase or self-generate.

Powell Valley’s power-purchase contract with the Tennessee Valley Authority prohibits the co-op from refunding capital credits, which is the excess money that member-owners paid over the year for their electric service.

Michael Shockley, a board member of Powell Valley Electric for about 15 years, told the Claiborne Progress that “the monies that we accumulate goes back into the co-op where it’s dispersed to where it can be best used.”

While Hurley notes that this is how the utility grows, he says it’s “very unusual” for member-owners to never have received capital credits, and he wonders how much the board has fought this policy.

“Which is one reason why some of us have been asking Powell Valley for a copy of their contract with TVA, and Powell Valley has not given it to us,” Hurley says. “‘What are these restrictions? And if they don’t allow these things, what are you [the board] doing about it?’”

“They don’t communicate all these details, they don’t survey all their customers, they don’t have any kind of town hall meetings,” he adds. “There’s almost no communication whatsoever between the board and their members, which is not the way it’s supposed to be.”

The systems governing utility monopolies were theoretically designed to serve the public interest, whether that utility is a rural electric cooperative with 30,000 member-owners or an investor-owned company with millions of ratepayers. But a litany of barriers including lack of transparency and putting shareholders above the public makes that difficult.

There are safeguards built into both systems to rectify these barriers, if the public chooses to do so. The next issue of The Appalachian Voice will examine how that can happen.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

3 responses to “The Problem with Monopoly Utilities”

-

There is no over sight when these so called elected officials have been bankrolled by the very corporations they pretend to govern in the name serving the public. While in reality serving nothing but themselves and corporate interests.

How many short-sighted and self-serving laws of ignorances have stained the American citizenry because of this??It’s all one big con.

On top that the entire ideology of maximizing shareholder profits is a disease upon civilization. The monopoly problem the American people see today was not built upon the back of individuality. Todays monopoly problem was fathered and fueled upon obese fat back of corrupt self-serving government.

Meanwhile society continues to blindly blame capitalism for such economic problems. When in reality these problems were caused by big government in bed with big business.

-

Yes, it’s time for major changes. We need new incentives for utilities and new rules that are more reflective of a world where much information is readily available. We can’t continue the system where our utilities control us and we have no ability to influence what occurs.

-

In the name of national security, either demand the utilities be non-profit or nationalize them.

Leave a Comment