Front Porch Blog

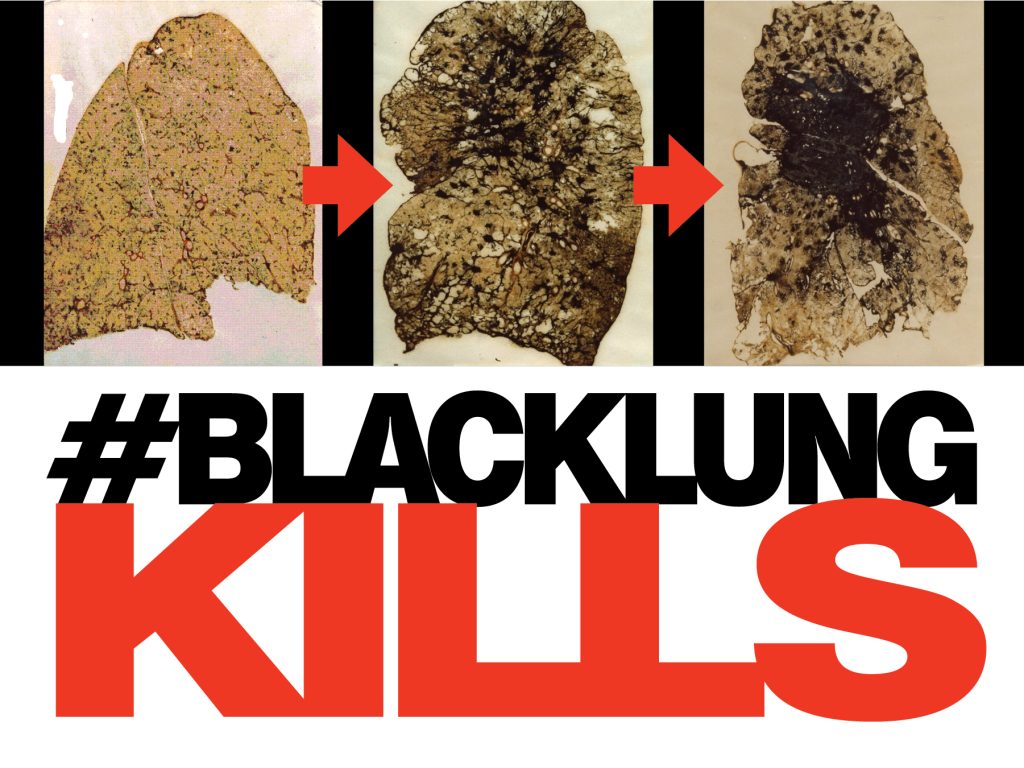

Black lung disease continues to devastate coal miners, their families and communities. The fatal disease has been at epidemic levels for years now, sparking a surge of grassroots activism by the Black Lung Association and others, including Appalachian Voices. These groups have scored some big wins under the Biden administration, including improvements to safeguards against miners breathing in silica dust — a chief culprit of the most severe form of the disease — and the permanent extension of the Black Lung Excise Tax, which coal companies pay into to fund medical care and disability benefits for miners with black lung.

Most recently, advocates applauded a new federal rule to close the self-insurance loophole, which coal companies have used to evade their obligations to employees with black lung through bankruptcy. Already, some congressional Republicans like Virginia Foxx, R-N.C., chair of the House Education and Workforce Committee, are attacking this rule, framing it as somehow anti-coal-miner.

In the meanwhile, a proposed merger of Arch Resources and Consol Energy, two of the country’s largest coal companies, demonstrates the need for this rule, and for regulators and advocates alike to be on high alert.

When a miner becomes disabled with black lung, their employer is required to provide disability benefits and pay for any needed medical care related to the disease. But in many cases when coal companies go bankrupt — a common occurrence in Appalachia — the federal government must step in and pay out these obligations through a program called the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, for which the aforementioned Black Lung Excise Tax is the only dedicated funding source.

Regulators are supposed to make certain that coal companies have adequate insurance policies to cover their obligations to employees who become ill with black lung. But historically, this oversight has been lax, and many companies have been permitted to “self-insure” their black lung obligations rather than secure an insurance policy from a reputable and adequately resourced insurance firm. “Self-insurance” is when a mining company assures regulators that it holds sufficient resources to pay out these obligations directly, rather than securing a policy from a third-party insurer as a backstop.

When “self-insured” companies go bankrupt, these obligations are offloaded onto the already strained trust fund. While revenues from the Black Lung Excise Tax now exceed the benefit obligations paid out, the fund remains insolvent due to historic debt, with the general treasury of the United States (meaning your tax dollars) picking up the slack.

Enter Arch and Consol, which announced their merger in August. Combined, these companies have estimated black lung liabilities in excess of $300 million. If these liabilities are not accurately secured post-merger — for instance, if the new company is allowed to self-insure — the risk to the trust fund would be extreme. Should this company go bankrupt without securing its massive black lung obligations, the result would be a huge burden on the federal government and the American taxpayers.

It does not bode well for the new company that when Arch last went bankrupt in 2016, it made headlines for its painstaking efforts to shirk both black lung and environmental reclamation obligations.

The new self-insurance rule is designed to prevent companies from underfunding their obligations and shifting the burden onto the government. Under the current rule, companies that self-insure only have to have about 19% of their liabilities backed by secure financial instruments. Under the new rule, companies will have to post assets covering 100% of projected black lung liabilities. This is a needed improvement, but there is still concern that the new rule may not be enough to protect the trust fund if the Department of Labor does not require companies to fully account for the true total cost of black lung obligations — a prospect that is especially alarming when discussing an entity as massive as a merged Arch/Consol would be.

Add to this the effects such a merger would have on both coal and labor markets. Combined, the two companies would control nearly 30% of underground bituminous coal mined annually in West Virginia and Pennsylvania — the largest coal producing states in the Appalachian region. In 2023, the two companies employed nearly a quarter of underground coal miners in these two states, and employed 10 to 20% of underground coal miners nationwide. In other words, this merger would create an incredibly dominant entity in Central and Northern Appalachia, which would reduce miners’ bargaining power and undermine job security, and which would harm consumers by driving up prices for electricity generation.

This is where antitrust regulations come in. Before allowing the merger to go through, it is critical that the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice carefully evaluate whether the companies’ black lung liabilities are adequately secured. If not, this could lead to further financial instability for the trust fund and an even greater burden on taxpayers.

As it stands, miners, their families and the taxpayers are the ones who bear the financial consequences when coal companies fail to meet their obligations. The new self-insurance rule is a significant step in the right direction, but it must be enforced rigorously, particularly in the case of such a large merger. A failure to adequately secure black lung liabilities in the post-merger company could have lasting negative effects on the trust fund, miners, and American taxpayers. The time to act is now, before the merger is finalized.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment