Front Porch Blog

In Pittsylvania County, Virginia, a beautiful county situated in Southern Virginia at the North Carolina border, communities simultaneously face pollution risks from three proposed major fossil fuel projects: a new gas plant from the developer Balico, a massive extension of the existing Transco pipelines and an extension of the ruinous Mountain Valley Pipeline.

Proposal one: Balico’s methane gas power plant

Determined local residents have already pushed the first of these projects back on its heels.

In mid-October 2024, residents noticed zoning documents on the Pittsylvania County government website that revealed that Balico, LLC had proposed a 3,500-megawatt gas plant to generate power for a campus of 84 data centers in Chatham, Virginia. The gas plant would create significant air pollution, and the data centers — a sea of two-storied buildings to be scattered across the land — would generate noise and air pollution. Balico had tried and failed to build a gas plant in another rural area in Eastern Virginia, Charles City County, some years back, but abandoned the project after massive community opposition and funding uncertainty.

The documents on the county site were the applications to rezone 2,200 acres of agricultural land in Chatham for industrial use. The community swiftly reacted in staunch opposition to the re-zoning and project. Adding to the ire was the fact that the process made it so far along without community knowledge or input. Hundreds immediately worked together to seek and share information, educate neighbors and voice their concerns to local elected officials on the Pittsylvania County Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors.

That fierce opposition worked — and within weeks, county supervisors, feeling pressure from their constituents, re-examined their own stance on the project and reflected on the hurt caused by the secrecy of this process. On Oct. 30, Banister District Supervisor Robert Tucker announced his opposition to the project. He said that he and other supervisors would ask Balico to withdraw its application. This victory was due to the hard and impassioned work of so many community members who galvanized opposition to Balico’s unsolicited plan for their beloved area.

After initially refusing, Balico withdrew their plan. But the company swiftly resubmitted on November 19, with plans for a smaller 300-megawatt plant and 12 data center buildings.

This segmented buildout has not tempered opposition within the community, as people recognize Balico is likely to try to expand its on-site infrastructure.

The Town Council of nearby Hurt recently revealed support for the project and that the town had signed an agreement to provide water for the Balico complex, drawing frustration from residents nearer the site that elected officials would try to influence the outcome of a project impacting in a neighboring community. Project opponents are staying engaged and very motivated— and will speak out against the current Balico proposal at both the Jan. 7 planning commission meeting and Feb. 18 board of supervisors meeting.

You can support this fight by attending the local meetings, to signal your opposition and to support the local residents who speak to elected officials.

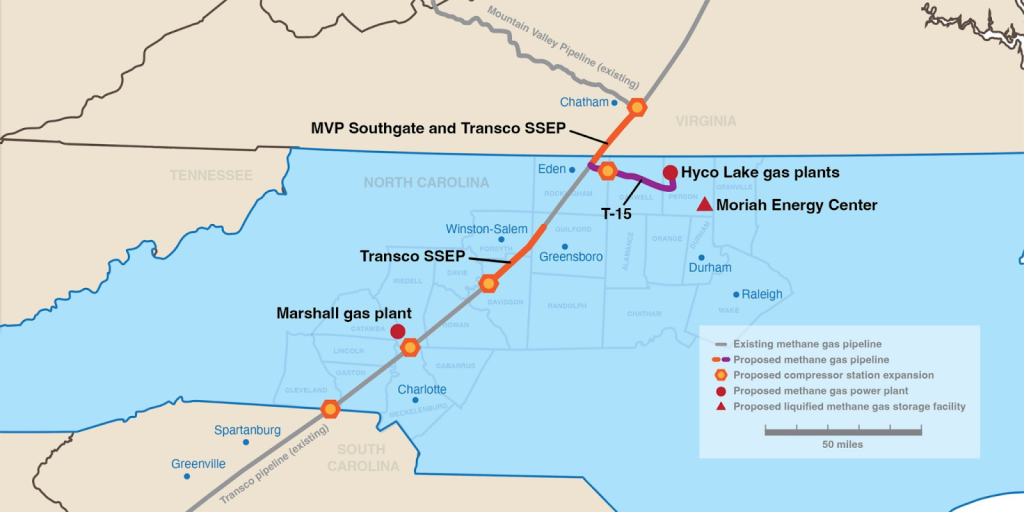

Along with the battle against Balico, Pittsylvania residents also face two potential massive fracked-gas pipelines. The polluting pipelines would have nearly parallel routes and possibly simultaneous review processes.

Proposal two: the Southeast Supply Enhancement Project / Transco pipeline expansion

First is the 42” diameter, high-pressure methane gas Southeast Supply Enhancement Project, an expansion of the existing Transco web of pipelines owned by Williams Companies in Pittsylvania County. The SSEP would pass through the southern part of the county, including Chatham. Chatham is also currently home to a massive, polluting compressor station which pumps gas for Transco’s existing lines. The pipeline would be routed through the Banister and Sandy rivers and snake for 26 miles through the county before extending into North Carolina, where it would repeatedly cross the Dan River. The Dan River is still recovering from a 2014 toxic coal ash spill by Duke Energy.

The SSEP is indicative of the overbuilding of fossil fuel infrastructure across the Southeast that would put an overwhelming burden on communities like Pittsyvlania. Gas pipelines mean methane leaks, sedimentation from construction and ongoing safety concerns. They put communities at increased risk from pollution and explosion dangers, and gas transmission lines in Virginia are not required to add an odorant, meaning a leaking transmission line would not give off any smell to warn of a problem. Compounding these concerns, Transco has one of the worst safety records of national pipeline companies, as detailed by the watchdog group the Pipeline Safety Trust.

Williams Companies, the project developers, recently applied to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for a Certificate of Public Necessity and Need for the project. The gas company requested a reduced assessment of the SSEP’s environmental impacts by asking FERC to perform an Environmental Assessment, instead of the more thorough Environmental Impact Statement.

Appalachian Voices and other organizations have pushed back on this request and demanded the most thorough review possible, with Appalachian Voices recently submitting a petition with over 2,800 signers. Once FERC releases its environmental report, the public will be able to scrutinize the agency’s opinion of the pipeline’s potential harms. FERC will host public hearings, including in Pittsylvania, and there will be a public comment opportunity. These will be important moments for the community to push back on this project and to highlight the harm SSEP would bring to the air, water and landscape of Pittsylvania.

In addition to the required FERC certificate, the SSEP has many other roadblocks. To begin construction, Williams Companies must obtain multiple state permits, including Clean Water Act 401 permits from both Virginia and North Carolina, and air permits for compressor stations in North Carolina. These permits will be under review in 2025 and robust public participation is needed in those review processes.

Adding additional concern is the proximity of the proposed SSEP to its competitor, the proposed Mountain Valley Southgate Extension. That dual set of construction, right-of-ways and possible sedimentation means all agencies should consider the combined cumulative impacts of the pipelines.

Proposal three: MVP Southgate Extension pipeline

The third project faced by Pittsylvania communities is the Southgate Extension, a resurrected extension of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. The mainline MVP reaches its end point in Chatham, after cutting through over 300 miles of mountains, farms and waterways in West Virginia and Virginia. The Southgate developer Equitrans Midstream wants to bring those same harms from Virginia into North Carolina.

Originally granted a certificate of necessity from FERC in 2020, Southgate failed to obtain any state level permits and could not move forward with construction. In Virginia, Southgate’s air permit application was rejected by the Air Pollution Control Board because of the disproportionate impact the project’s compressor station would have on the surrounding community. In North Carolina, Southgate’s water permit was rejected after the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality determined that work on the pipeline extension could “lead to unnecessary water quality impacts and disturbance of the environment in North Carolina.” Those denials were important moments of community victories, and in Pittsylvania, the local branch of the NAACP played a critical role in stopping the compressor station.

Denied those state permits, the project lay dormant for years and developers halted eminent domain proceedings to forcibly obtain personal properties in North Carolina. During this period, nearby communities watched the Mountain Valley Pipeline mainline project result in landslides, muddy waters and suffer pipe failures during testing.

Although Southgate developers made no effort to move the pipeline forward between 2021 and 2023, FERC unfortunately granted the company’s request to extend its certificate of necessity for three more years, to 2026. Only 10 days after receiving that extension, Southgate developers shockingly announced a major rewrite of the pipeline’s route, length and capacity. That new design would mean a significant capacity increase to 550,000 dekatherms per day of gas in the line. That means increased downstream greenhouse gas emissions and more pollution. Nearly a year after that announcement, communities wait for the pipeline developers to submit an amendment to FERC, and for required state level permits to come under review.

This deja vu means overlapping reviews, hearings and public comments periods for both Southgate and SSEP in 2025. Navigating these processes is time-consuming and difficult and is a burden on communities who are simultaneously dealing with Balico’s interference in their lives.

Pittsylvania County is at a center of overbuilding of fossil fuel infrastructure. As community members, experts on their beloved region, continue to work hard to reject harmful projects like the Balico gas plant, SSEP and Southgate, their inspiring organizing also makes Pittsylvania County a center for determined community advocacy.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

One response to “Pittsylvania County, Va., is at the center of an overbuilding of fossil fuel infrastructure”

-

The abandonment of once vital rural areas by manufacturing has left our region open to projects such as the three listed here. Projects sold as providing jobs, but there is scant evidence they do. These projects are seized upon by local officials because what little local revenue they provide is sorely needed by local government, and at the same time provides investment opportunities for the upper classes, who will never see or care about these zones of sacrifice. We should have launched an effort in the 1970’s to move away from so called fossil fuel, but instead we trusted corrupt men to lead us through the forest of choices to be made. It’s no wonder these people now want to lay waste to large areas in order to transport the very commodities they openly champion today. Our problem lies in misplaced trust and fear. Kudos to the author, and those on the ground opposing these toxic developments. They’ve always been a poor trade for our environment and communities, because they destroy both, with no benefit to the residents.

Leave a Comment