Front Porch Blog

Zombie mines are an escalating issue in Tennessee. These are abandoned or inactive coal mining sites where coal companies have failed to meet their obligation to clean up their mines.

Zombie mines often evolve into environmental hazards, leaking pollutants into waterways, disrupting natural areas and creating dangerous landscapes. With no responsible operator to oversee the process of mine cleanup, known as reclamation, the burden frequently falls to surety companies (insurance companies that agree to cover reclamation in exchange for a fee) and, potentially, the state and taxpayers. Bond forfeiture in surface coal mining occurs when a mining company fails to meet its reclamation obligations, prompting regulatory authorities to seize the financial assurance (bond) posted by the operator. The forfeited funds are then used to cover the costs of reclaiming the disturbed land, though they often fall short of the actual expenses required for full restoration.

A recent report, submitted by the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation to the state legislature and governor’s office, underscores the urgency of this crisis. Mandated by Senate Bill 808 of 2023, the 2024 Primacy Report reveals startling statistics: $34.4 million in underfunded reclamation bonds, 53 out of 79 mining permits in bond forfeiture, and no coal mined in Tennessee since June 2022. These figures illustrate the coal industry’s decline and the proliferation of zombie mines.

Kopper Glo Mining: A case study in reclamation failures

The Clearfork Community Water Testing program in Northeast Tennessee has monitored the impacts of zombie mines for years, documenting significant damage caused by coal companies. They have consistently documented environmental damage caused by companies like Kopper Glo Mining, LLC, whose numerous bond forfeitures illustrate the state’s growing reclamation crisis. Approximately two-thirds of Tennessee’s inspectable coal mines are now in some form of bond forfeiture.

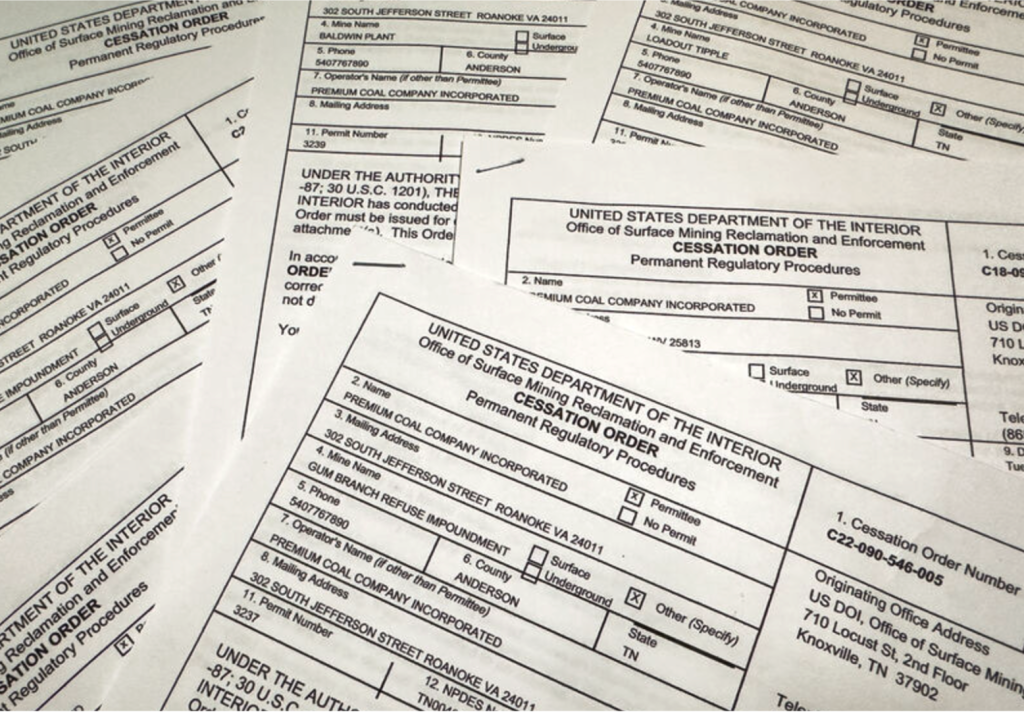

Freedom of Information Act requests fulfilled by the federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement in March and November revealed a multi-million-dollar bonding shortfall across Kopper Glo’s operations. Although the company’s surety provider has assumed responsibility for reclamation at several sites, many of these sites’ reclamation liability exceeds its bond, and while they are left unreclaimed, serious safety concerns remain.

- At permit 3229, the mine gate and portals remain open, posing serious safety risks.

- At permit 3280, known as “The Refuse,” there’s a $600,000 shortfall between the funds available for cleanup and what full reclamation is expected to cost. An estimate by OSMRE earlier in the year had the difference between reclamation and costs and available resources even higher — at $2.3 million. This coal waste site has led to erosion washing out local roads, and TDEC reports that its pond is discharging selenium, a toxic element harmful to aquatic life.

Justice family-owned operations: Ongoing compliance issues

Mining operations owned by West Virginia Senator-elect Jim Justice’s family in Anderson County face similar challenges. Mines operated by National Coal Company and Premium Coal Company are undergoing bond forfeiture proceedings, with appeals through the Interior Board of Land Appeals delaying critical cleanup work.

Two sites stand out for their risks:

- The Baldwin Tipple area in Anderson County was issued an Imminent Harm Cessation Order. Its raw coal yard is currently inundated with water, which is not an approved usage of the permit and possesses a small risk of breaching in a significant rain event.

- The Gum Branch Refuse impoundment is also allowing iron-laden mine water to flow from Pond 1 to Pond 5 across the road and from there into the Tennessee New River, due to a pumping failure.

The broader impact

The zombie mine issue in Tennessee reflects a larger crisis in coal regions across the United States. As the coal industry declines, more operators abandon reclamation responsibilities, leaving a legacy of environmental degradation and public safety risks. These sites pollute our land and water and endanger people living nearby, with an increasing risk of cleanup costs potentially being shifted to taxpayers.

Stronger protections, and potentially reforms to the 1977 Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act, may be needed to prevent the zombie mine crisis from escalating and leaving future generations to bear the consequences of today’s inaction. Increased accountability and enhanced oversight are vital to ensuring that the coal industry fulfills its reclamation responsibilities as it continues to decline.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment