Front Porch Blog

A bankruptcy of any one of nine coal companies could tank the state of Virginia’s mine reclamation fund within a decade. This is according to a February actuarial study by Taylor & Mulder, Inc. commissioned by the Virginia Department of Energy and obtained by Appalachian Voices on Oct. 28.

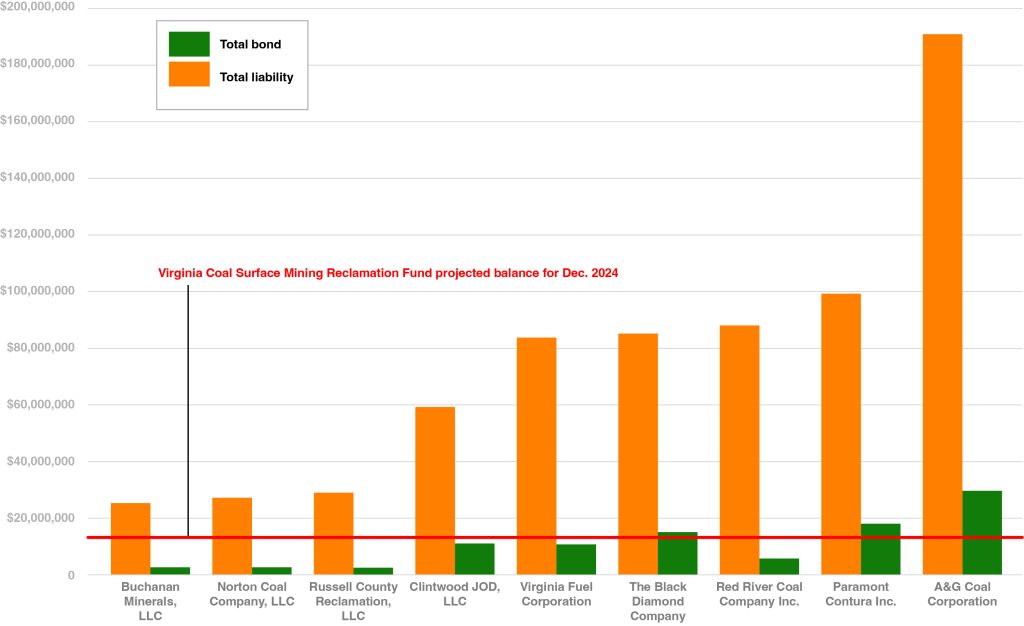

Virginia’s Coal Surface Mine Reclamation Fund, which is essential to ensuring the state can clean up coal mines when industry fails to do so, is projected to hold around $13.2 million at year’s end, according to the study. There were around 180 mines backstopped by this fund as of August, based on information provided to Appalachian Voices by the Virginia Department of Energy.

Topping the list of companies that could threaten the fund’s solvency is A&G Coal Company, majority-owned by West Virginia Gov. and Senator-elect Jim Justice. Listed in descending order according to total cleanup liabilities, the other eight companies are Red River Coal Company, Paramont Contura LLC, Virginia Fuel Corporation, The Black Diamond Company, Clintwood JOD, Russell County Reclamation LLC, Norton Coal Company LLC and Buchanan Minerals LLC.

Prior to commencing mining operations, coal companies must post a bond. Regulators can use this bond to fund reclamation if a company fails to do so, a scenario known as bond forfeiture. Many bonds take the form of assurances from a third-party financial institution or surety company, but mining operations may also participate in state-run pool bonds like Virginia’s Coal Surface Mine Reclamation Fund.

Pool bonding requires coal companies to contribute a fraction of the anticipated reclamation and environmental cleanup costs for a given mine into the state-managed fund, which regulators can draw from if any mine participating in the pool goes belly up.

In Virginia, pool bonds for surface coal mines are based on a flat, per-acre assessment of $1,500 for surface mines and $1,000 per acre for underground mines, starting at a minimum total of $100,000. The state does not take site-specific factors, such as the potential need for long-term treatment for water pollution, into account when calculating pool bond requirements. This results in a pool bond that is likely even more under-funded than it is designed to be. The fund is also financed by a tax on coal produced from pool-bonded mines at a rate of 4 cents per ton for surface mines and 3 cents per ton for underground mines.

The theory behind pool bonding is that only one or two mines participating in the pool will ever face bond forfeiture at a given time, so regulators will never need to access the full amount necessary to reclaim every mine in the pool.

But here’s the problem: the state of Virginia, and the whole Appalachian region, are running low on coal deposits to mine. This is partially the result of being more than two centuries into extracting a finite resource from our region, and it’s partly because energy markets have largely moved on from Appalachian coal, thanks to cheaper sources of energy production winning out in the markets. (Yay, renewables! Boo, fracked gas!)

Meanwhile, regulatory loopholes and lax enforcement have enabled companies to defer environmental compliance and reclamation for many years, producing the current zombie mine crisis facing Appalachia. As a result of these converging factors, the likelihood of one or more coal companies becoming insolvent and jeopardizing the pool bond is rising.

The threat posed by A&G is particularly acute. The new study estimates that the outstanding reclamation costs of A&G’s mines in Virginia is $190.4 million, more than 14 times the total balance of the Coal Surface Mine Reclamation Fund.

Like other companies in the sprawling empire of Jim Justice and his family, A&G has a truly dreadful history of environmental non-compliance. Along with Southern Appalachian Mountain Stewards and Sierra Club, Appalachian Voices is currently embroiled in litigation with the company over their failure to reclaim three massive mountaintop removal mines in Wise County, Virginia. At the end of October, we filed a motion to hold the company in contempt for yet again missing reclamation deadlines, failing to maintain operational reclamation equipment and mining coal in violation of a previous court order.

What’s more, most of A&G’s mines are self-bonded. This is when a company simply provides some basic financial information, and gives regulators its word that it will complete reclamation instead of providing a letter of credit, surety policy, or something else of real value as a bond to secure funds for reclamation. This self-bond assurance is undermined by the long history of vendors, regulators and employers struggling to compel the Justice companies to pay its debts. In August, attorneys for A&G and 27 other Justice family companies admitted in court that the companies are unable to pay $600,000 owed for health and safety violations as part of ongoing legal entanglements with the Department of Justice.

Self-bonding is no longer allowed for new mines in Virginia.

Virginia Fuel Corporation, another Justice company, also made the Taylor & Mulder study’s shock loss list with $83.6 million in reclamation liabilities, more than six times the total balance of Virginia’s pool bond.

Other companies of particular interest to Appalachian Voices whose bankruptcies pose a threat to the bond pool include Clintwood JOD, with $59.1 million in liabilities, more than four times the balance of the fund, and Russell County Reclamation, LLC, with $29.1 million in liabilities, more than double the balance of the fund.

Clintwood JOD’s operations in Buchanan County have been the frequent subject of community complaints over dust and other issues. The company has also recently successfully petitioned the state for more lenient monitoring and control of selenium pollution in waterways.

Russell County Reclamation, LLC holds the permit for the former Moss #3 coal preparation plant, in Cleveland, Virginia, where community members recently mounted a successful campaign to stop the company from repurposing the property as a landfill.

The Taylor & Mulder study asserts that, barring any major bankruptcies resulting in bond forfeitures, Virginia’s bond pool is on track to remain solvent for several decades. But this conclusion is based on certain assumptions. To their credit, Taylor & Mulder acknowledge the potential for market forces and other factors to undermine these assumptions. Namely, their solvency projection rests upon an expectation that the rate of bond forfeitures will remain as low as it has in the past and that coal production, and thus coal tax revenue, will proceed in line with projections by the Energy Information Administration.

Additionally, site-specific conditions are not reflected in the data underlying the study’s liability and forfeiture-rate estimates. The study does consider the type of mining operation and the status of the mining permit (actively moving coal, inactive, partially reclaimed, etc.) in its calculations, but significant variation in outstanding cleanup costs can still exist among operations of the same type and permit status.

The study also assumes that a maximum of $3.5 million could be spent out of the Coal Surface Mine Reclamation Fund in a given year, and that each company has only a .5% chance of going bankrupt in any given year. While it is fair enough to consider limitations to how expeditiously Virginia could complete reclamation work and spend down the fund, the report does not explain how Taylor & Mulder arrived at this $3.5 million figure. There is likewise no explanation for why they set the likelihood of bankruptcy at a flat .5% for all companies, when it is entirely plausible that some companies, like A&G, may be on the brink of collapse, while others may be comfortably solvent.

The Taylor and Mulder study confirms what we at Appalachian Voices already knew — Virginia’s pool bond is under-funded. To get a handle on the situation, the state should require companies to post bonds for the full cost of outstanding liabilities, provided in the form of cash, letters of credit or surety policies, for all mines permitted in the state.

More importantly, when you’re deep down in a hole, you need to stop digging. It’s high time we quit allowing the coal industry to raze the mountains of Southwest Virginia in the first place.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment