Front Porch Blog

Special to the Front Porch: Richard Miller is a former congressional staffer and served as the Labor Policy Director for the Committee on Education and Labor. (This was initially posted on Confined Space, a newsletter of workplace safety and labor issues.)

Special to the Front Porch: Richard Miller is a former congressional staffer and served as the Labor Policy Director for the Committee on Education and Labor. (This was initially posted on Confined Space, a newsletter of workplace safety and labor issues.)

This three-part guest blog examines the lengths coal companies will go to in order to evade their obligations to miners who develop black lung disease while working for them. Part I below explains black lung and the benefit system in place for miners with the disease. Part II discusses how companies short-change that system. Part III examines potential solutions.

A continuous miner in action.

For more information on how the coal operators fight miners black lung claims, read “Soul Full of Coal Dust: The True Story of an Epic Battle for Justice,” a gripping story by award-winning investigative journalist Chris Hamby about how the coal industry, backed by their stable of the best attorneys and “expert” doctors money can buy, cheated thousands of miners suffering from black lung, out of the compensation they deserved.

Yet it is the complexity of this story that helps hide this scandal from the American public, even though the result is that the taxpayers are bailing out wealthy coal operators for the costs of black lung disease that has doomed tens of thousands of mineworkers over the past half century.

So, sit back, pour yourself a drink, and spend a few minutes to understand how coal operators and Wall Street continue to manipulate the law and threaten miners’ health while picking taxpayers’ pockets.

Black lung disease has contributed to the deaths of more than 76,000 coal miners since 1968. Facing rank-and-file uprisings across the Appalachian coal fields, Congress passed the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 to improve safety and health standards for miners and institute the first enforceable coal mine dust standard. That standard drove down black lung rates for more than 30 years.

Until it didn’t.

In the early 2000s, the most severe form of black lung disease (known as progressive massive fibrosis) came back with a vengeance driven by higher exposure to silica in coal mines. In 2018, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health reported one in five long tenured miners in Central Appalachia was diagnosed with black lung disease — a rate not seen in 25 years.

The 1969 mine safety act also included a national compensation system for miners suffering from black lung disease. That program, which is now administered by the Labor Department, provides totally disabled miners and survivors with $738 per month plus related medical costs, and another $368 per dependent up to a maximum $1,475 for a family of four. Obviously, no one is getting rich by winning a claim for an irreversible lung disease that slowly suffocates its victims.

Who is responsible for paying black lung benefits?

In general, mine operators are responsible for paying black lung benefits. But coal operators use bare-knuckle tactics to fight miners’ black lung claims, making it an uphill battle for claimants to secure the benefits they have earned.

As part of the claims process, the Labor Department identifies the miner’s last coal mine employer (where the miner was employed 12 months or more), who is deemed the “Responsible Operator” liable to pay any black lung benefits awarded. To ensure that mine operators have the funding to pay the miners’ benefits, operators must purchase workers’ compensation insurance to cover black lung benefits.

As coal seams dwindle, miners must cut through large amounts of sandstone in order to access dwindling supplies, exposing the miners to increased levels of silica dust. Inhaling the dust scars the lungs worse than coal dust, and leads to black lung disease. The Black Lung Association and other advocacy groups are pushing for the Department of Labor’s Mine Safety and Health Administration improve regulation of silica dust in coal and other mines. Photo courtesy of CDC.gov

Or there is another option: Mine operators are allowed to self-insure — if they can demonstrate to the Labor Department that they have secured the necessary assets to cover their black lung liabilities.That’s an attractive option for many coal operators since self-insuring often costs less than buying workers’ compensation insurance.

But how does the Labor Department make sure that the self-insured operators have the full amount reserved for current and future benefits? And how can these assets be secured before there is a bankruptcy?

Under current rules to self-insure, operators must have been in the business of coal mining for at least three years and demonstrate to the Labor Department that they have sufficient assets to cover their black lung liabilities by obtaining collateral in the form of an indemnity bond, placement of assets in escrow, or a letter of credit in the amount necessary to secure payment of benefits.

That way if (or when) they go bankrupt, the funds are there to pay benefits — in theory. But who pays if the coal operator goes bankrupt and doesn’t have enough commercial insurance? And what happens if the operator hasn’t reserved sufficient assets to pay current and future benefits (or purchased an indemnity bond to cover these costs)?

In cases where no responsible mine operator can be identified, the operator went out of business, or the operator filed for bankruptcy, the benefits are paid by the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, which was established in 1978 by the Black Lung Benefits Revenue Act of 1977.

The trust fund is financed by an excise tax on coal tonnage amounting to $1.10/ton for underground coal and $0.55/ton for surface mined coal. The tax is paid by mine operators for coal sold domestically (exported coal is exempt). But the revenues from that tax have never been sufficient to cover the trust fund’s expenses, and the fund is currently approximately $6 billion in debt.

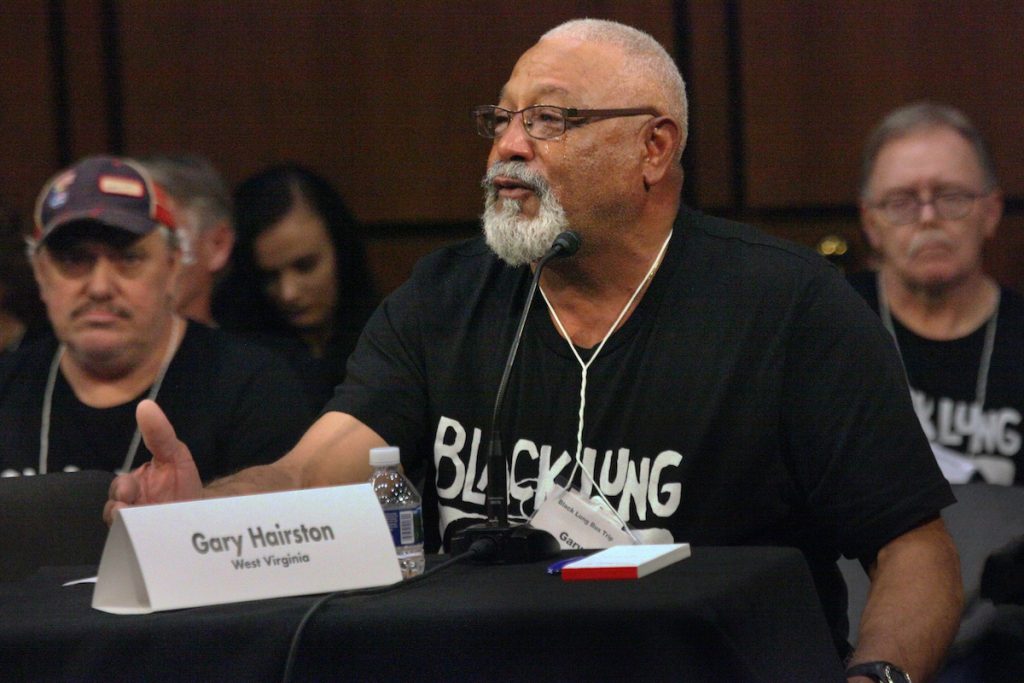

Gary Hairston of the Black Lung Association testifies at a Senate panel in 2019. Photo by Earl Dotter, earldotter.com

A shrinking industry and shrinking funding for the Black Lung Trust Fund

With limited exceptions, domestic coal mining is a rapidly shrinking industry. Bankruptcies have proliferated because there is only half as much domestically mined coal as there was a decade ago. Even though Congress took steps to shore up the trust fund in 2022 when it restored the black lung excise tax rate, trust fund revenues will keep falling in lock step with cuts to coal tonnage. But miners who contract disabling black lung — and their survivors — will still need to receive benefits long after their employers have ceased to mine coal. This liability “tail” could last as long as 50 years, according to the director of the Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs in the Trump Administration.

The good news is that even if the trust fund does not have sufficient resources to pay benefits, miners’ black lung benefits are still OK because the trust fund is authorized to borrow from the U.S. Treasury if it is short of funds.

The bad news is that, ultimately, if the trust fund is insolvent, it’s the taxpayers — you and me — who end up paying benefits for miners with black lung instead of the coal companies that caused the problem in the first place.

Up next: How companies game the system.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Another excellent example of privatizing the profits & socializing the expenses. Hoo Rah for good old-fashioned capitalism & Adam Smith-style capitalism.