Black Lung Advocate Judith Riffe is Making Change (and Quilts) in West Virginia

By Hannah Wilson-Black,

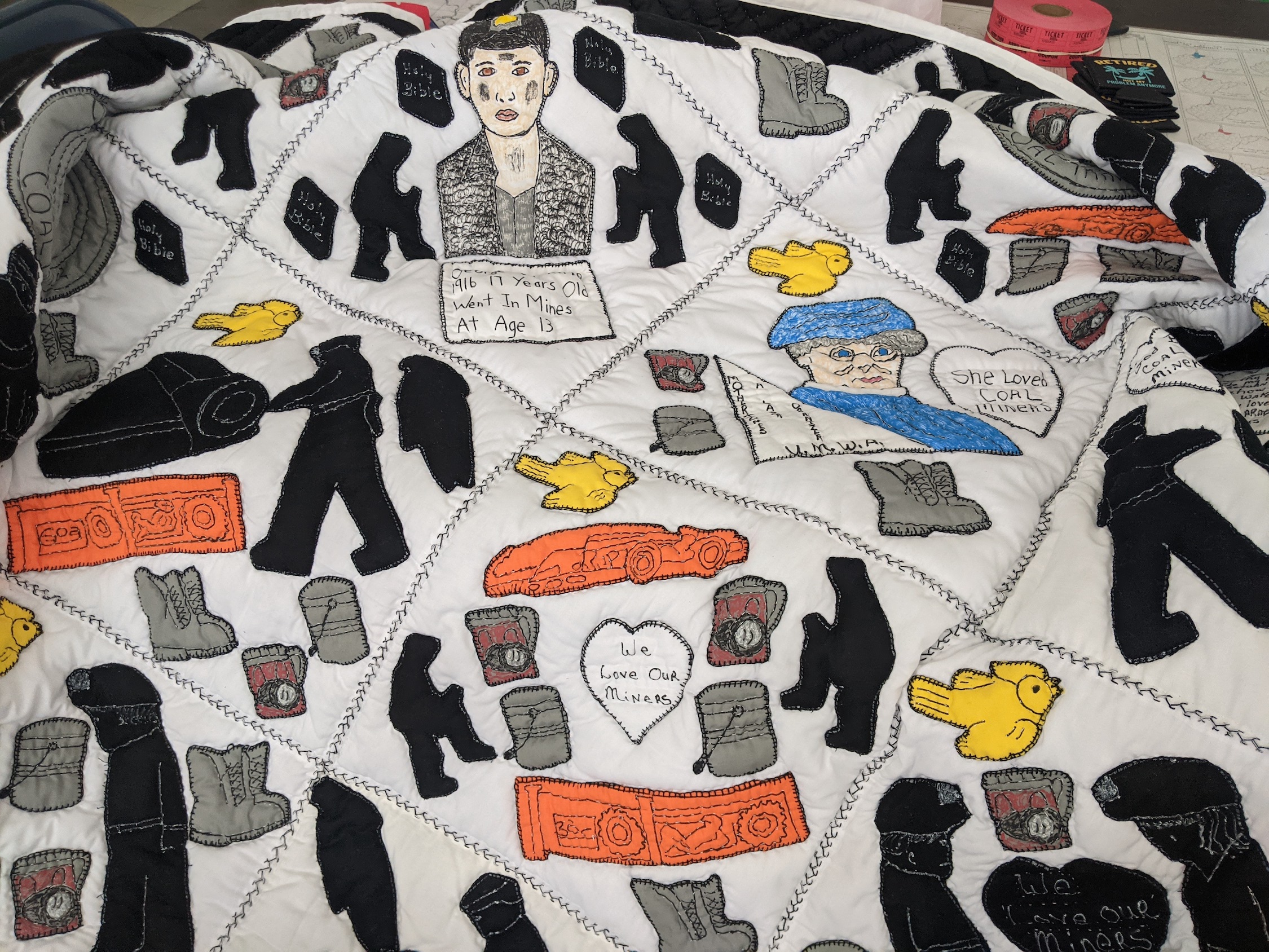

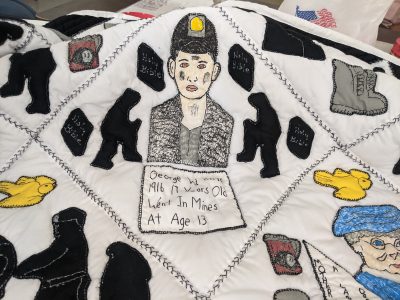

Judith Riffe crafts and sells quilts honoring miners to raise funds for the Wyoming County Black Lung Association. Photo by Willie Dodson

From a single-parent home in McDowell County, West Virginia, to MSNBC’s town hall stage, Judith Riffe has lived a remarkable life. But she retains a down-to-earth humility in her warm voice.

“I’m not educated,” she says, though her thorough knowledge of black lung law would beg to differ, “but I can quilt, I can sew.”

And quilt she does. Riffe is secretary of the Wyoming County Black Lung Association, one of many Black Lung Association chapters that meet regularly to support miners and their families as they struggle with the disease and apply for federal black lung benefits. She makes and sells quilts to fundraise for the chapter, raising more than $5,000 so far. Some are custom pieces that buyers pay hundreds of dollars for. Others honor coal miners, their images sewn into the blankets that Riffe makes by hand.

One quilt was particularly personal to Riffe.

“I had put my father-in-law on it,” she says. “My father-in-law had went in the mines when he was 13 years old.”

Riffe’s late husband Bernard, who passed away in March 2021 at the age of 78, also went into the mines as a teenager. He started shoveling coal by hand at the age of 15. When he passed away in the spring, black lung was to blame.

“Of course,” Riffe says, “we went through the whole procedure, you know, all the doctors and oxygen.”

“You live it with them,” she says of the disease. “We were married almost 58 years. We led a close-knit life.”

Riffe talks about her late husband with wonder and love. He had a knack for home repair and was easily excited, though slow to anger. It was hard to rile him up —”he was not a high-tempered man,” she says — but he was a passionate union member who cared deeply about his work in the mines and his fellow miners.

“It was amazing,” Riffe says of his skills around the house. “I can tell him I wanted the kitchen done a certain way or something. He’d know how much material to go get, you know, he was just gifted. I never had a carpenter in my house. I never had an electrician in my house, I never had a mason, nothing.”

Riffe and her husband adopted one son and have six “love grandchildren” through close friends who are like family. One, a 10th grade boy, is his high school’s starting quarterback.

When she’s not cheering her grandson on at high school football games, Riffe is working with the Black Lung Association, selling her quilts, tabling at big county events, and helping miners start the claims process for black lung benefits.

In fact, Riffe was invited to speak on MSNBC when Sen. Bernie Sanders visited McDowell County in 2018 and hosted a live town hall event. A Black Lung Association lawyer suggested Riffe as a spokesperson for miners in the area, and before she knew it, she was answering questions from anchor Chris Hayes along with fellow West Virginia panelists, speaking live to a television audience.

“I thought I would be real scared,” Riffe recalls. “But they just make you feel easy, you know. I wasn’t scared or anything.”

“I told them the story of black lung,” she says. Riffe recounts how President Richard Nixon signed the Black Lung Benefits Act into law in 1972, but the process for filing claims was incredibly onerous, particularly under the Regan administration. In the first three years of the program, the Labor Department approved only 8% of claims. This number rose to 50% in 1978 under the Carter administration but dropped to 4% after President Ronald Reagan took office in 1981 and signed a bill making the benefits approval process much stricter.

Take Action to Support Black Lung Benefits

The Black Lung Disability Trust Fund provides healthcare and a small living stipend to miners with black lung when the company responsible for their disease is unable to pay, typically due to bankruptcy. The sole funding source for the trust fund is a tax that coal companies pay on each ton of coal mined.

When Congress failed to pass a four-year extension of the Black Lung Excise Tax in the Build Back Better Act before the new year began, that single source of revenue for the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund was cut by more than half. Now, black lung advocates estimate that the trust fund is losing more than $2.8 million per week.

Ask your legislators to shore up this important fund by extending the tax. Send a quick letter here.

“Reagan made it so hard for the miners to get their black lung benefits. They just couldn’t hardly do it,” Riffe says. But according to Riffe, the system was improved considerably in 2010 when West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd sponsored two amendments to the Affordable Care Act which codified a presumption that black lung is the cause of any evident respiratory impairment for miners who worked at least 15 years in the mines, thus putting the burden of proof on coal companies who wish to contest a black lung claim, rather than on miners and their families attempting to file such claims.

“Our Senator Byrd was wheeled out on the Senate floor in a wheelchair when they were passing the Affordable Care Act,” recalled Riffe. Byrd was the longest-serving senator in U.S. history at the time of his death just three months after championing the ACA’s black lung provisions.

The 2010 changes put the burden of proof back on the employers of disabled miners who have worked 15 years or more to prove that the miners do not have black lung, rather than requiring miners or their families to prove that they have it or that the miner’s death was caused by it. The benefits approval rate now hovers at around 30%.

Judith Riffe has raised over $5,000 for the Wyoming County Black Lung Association. She encourages others to use their talents to support the work. Photo by Willie Dodson

According to Riffe, the television audience in Welch, West Virginia, connected with her comments because “they had seen women lose their husbands and even women died, and the spouses have to have autopsies done and everything to show that they did have black lung.”

In addition to fundraising with her quilts, Riffe is also working with the Wyoming County chapter of the Black Lung Association to erect a statue of a female coal miner in her hometown of Mullens, West Virginia, to stand alongside the statue of a male miner that is currently there. The memorial consists of two curved walls of bricks that form a half-circle behind a statue of a man in mining clothes with equipment in his hands. Many bricks have names engraved on them, and supporters can purchase bricks to engrave.

While the majority of mine workers are male, there are also women among the workforce. Historically, Mullens and nearby communities in Wyoming County, West Virginia, had one of the higher rates of women working in the mines.

“I’m hoping when we put up the woman [statue] then a lot of the women will come and buy the bricks and help the memorial to build,” says Riffe.

The woman’s statue was made by the same North Carolina pottery studio that created the original man’s statue, Slick’s Pottery in Mount Airy. To make the statue, the sculptor of the original male miner altered his earlier clay model to make it look more feminine. The pottery studio then had a new rubber mold made from the revised clay model and filled it with concrete and granite dust to create the finished statue.

The new statue has now arrived in Mullens and is being stored at Riffe’s home while she works with the town to coordinate its installation. Riffe said an unveiling date is still to be determined, but she plans to make the statue’s dedication a special occasion, with local politicians in attendance, and a dinner at the Mullens Opportunity Center to follow.

Riffe describes the overall work of the Black Lung Association as, “Just to try to help as many miners as we can get their benefits, and to encourage them not to quit. So many of them, you know, they say, ‘I’ve tried and I’ve tried. I can’t get it. They ain’t gonna give it to me. They just won’t do it.’

“And you know, to encourage them, [I say] ‘Don’t give up. You’re living, keep trying!’”

The Wyoming County Chapter of the Black Lung Association meets on the second Monday of each month at 5 p.m. at the Mullens Opportunity Center, 300 Front St., Mullens, West Virginia.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

I would like to speak with you about trying to get my benefits. A friend of mine as well.