Front Porch Blog

This is the second in a series of blogs examining the damages caused by acid mine drainage and solutions for cleanup. Click here for the full series and related materials.

In this second blog about the acid mine drainage (AMD) challenge, advocates for abandoned mine land restoration are looking into potential solutions being considered right now and how they may — or may not — help solve this problem. Congress is currently considering a bipartisan infrastructure bill with $11.3B in potential investments in abandoned mine land (AML) clean-up, raising new questions about what this money could do and cannot do to tackle AMD issues, how states can respond, and why it is so important to get this right. To help explain the proposal, its benefits, and its drawbacks, we were pleased to have an in-depth conversation with Joe Pizarchik.

Originally from southwestern Pennsylvania, Pizarchik served as the director of the Bureau of Mining and Reclamation within Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection before serving as Director of the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement during the Obama administration. He is one of the nation’s foremost experts on complex and sprawling abandoned mine lands issues, and here he provides an essential overview of how AMD fits into pending legislative proposals and where we should look next.

See part 1 in our AMD blog series: Confronting acid mine drainage: A conversation with Rural Action’s Marissa Lautzenheiser.

Q: What is the value in treating AMD?

Pizarchik: One of the biggest values is the permanent, well-paid jobs created to operate and maintain the AMD treatment systems, whether they’re passive treatment systems for smaller discharges or large treatment plants. It also creates temporary jobs whenever that system needs to be rehabilitated. Those jobs aren’t going to be outsourced.

The Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission did an analysis of how much the polluted streams in Pennsylvania are costing everybody. They documented that there are 5,559 miles of streams that are polluted with acid mine drainage. And because those streams are not fishable, the annual loss of revenue here on average is $29 million in angler-generated revenue.

That’s just for the people who would go fishing. If you restore streams, you get even more local revenue generated from other recreation such as boating, kayaking or camping.

Q: What are some examples you’ve seen of this kind of progress?

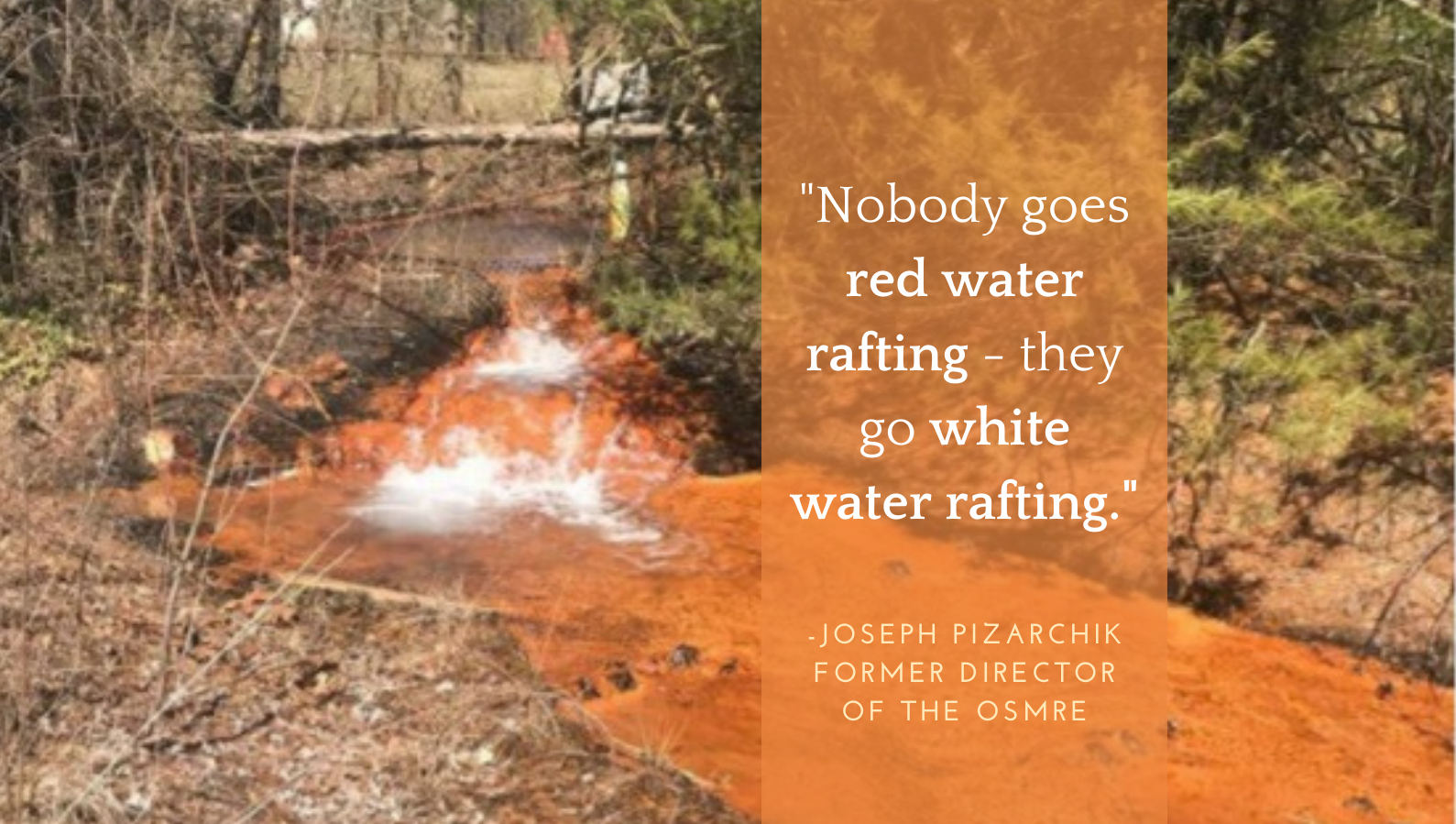

Pizarchik: Near Johnstown, Pennsylvania, the Conemaugh River and Stoney Creek were polluted with acid mine drainage for years. Progress has been made on cleaning up that acid mine drainage, and as a result a new business was created for whitewater tubing and kayaking. Nobody goes red-water rafting — they’ll go whitewater rafting.

In North-Central Pennsylvania there’s a stream called Kettle Creek. The headwaters of it had wild trout in it, but downstream the creek was devoid of all aquatic life due to acid mine drainage. Trout Unlimited worked to build a number of passive treatment systems to deal with those discharges. Those systems restored miles and miles of stream for wild trout. The initial thought was that it would take a couple of years for the trout to repopulate it. But within months after the last systems went online and cleaned up the water, there were wild trout in that whole part of the stream.

Q: We’ve heard of the historic pending $11.3-billion investment in abandoned mine lands clean-up in the bipartisan infrastructure bill, but understand there are some shortcomings as well. Can you speak to the gaps you see in the language of this bill and its current version?

Take Action

Tell Congress to let states use their infrastructure funding for acid mine drainage treatment!

Pizarchik: The $11.3 billion for abandoned mine land is a very good contribution to a long-suffering need. But the bill could be even better if it allowed states the freedom to restore streams poisoned by acid mine drainage

The bill also fails to allow funds to be used for the operation and maintenance of hundreds of treatment systems that were built by volunteer good Samaritans. And instead, it relies on them — who often are just folks who are out trying to raise money through bake sales or raffles — to maintain these systems. Hundreds of miles have been improved. But there’s no funding stream to maintain those systems even though there was funding to help build them and that is what is needed.

Q: Can you speak about the Casey amendments? What do those include and why is that so important?

Pizarchik: Senator Casey had the intelligence to see that communities will never prosper without clean water. There are countless examples throughout Appalachia — and also throughout Pennsylvania — where acid mine drainage is still holding communities back.

His amendments would allow states to use some of this $11.3 billion to treat acid mine drainage that is not adjacent to abandoned mine lands. Right now, the law does not allow a state to spend money to treat acid mine drainage unless the discharge is adjacent to a high-priority site — a Priority 1 or Priority 2 site. In addition to that, the Casey amendments would allow states to set aside some of the money to pay for future operation and maintenance of a treatment system that they built.

A passive treatment system typically does not require a lot of operation and maintenance costs. But many discharges are so big that the only way to treat them is to build a conventional treatment plant. A state’s not going to spend the money to build one of those treatment plants if it does not have the money to operate and maintain it into the future. Senator Casey’s amendment would allow the states to put aside infrastructure bill money for that particular purpose.

There are numerous examples where coal companies built tunnels to drain the water out of a coal mine. These tunnel discharges are tens of millions of gallons a day and are miles away from the abandoned mine lands. Without the flexibilities that Senator Casey’s amendments include, this acid mine drainage and these miles of stream pollution will never be addressed.

Q: Are there other changes that you’d like to see to the way that the funding is structured in the infrastructure legislation to make it even more impactful?

Pizarchik: Yes. The bill could have more of a positive impact if it provided for or at least encouraged local citizen input. Some states work with the local communities on helping to plan and or decide which AML problems to address. But not all states do that. And there are numerous instances where the public is excluded from the process of cleaning up these resources. It’s their communities, their land, their water — they ought to have some input on what they think is the most important in their area to have addressed first.

It would also be helpful if some priority was given to restoring abandoned mine lands on public lands, such as parks and state forests.

Another huge opportunity is to prioritize the restoration of native forests on these reclaimed, abandoned mine lands. That’s particularly important because if you restore the native forest, it has multiple benefits. It’s going to pull carbon out of the air — much of which got there from burning coal — which will help reduce or limit some of the adverse climate impacts we are experiencing today. It will provide for more clean water because those forests will limit or stop erosion and sedimentation. And, they create habitat for wildlife.

If all you’re doing is eliminating the hazard, you’re missing an opportunity to do more to help the environment, and the people and the climate.

Q: What can states do to prepare for this potential influx of funding if the proposal for $11.3 billion passes?

Pizarchik: States should start planning now to hire the staff that they need. If the bill is passed [to add $11.3 billion to address AML issues], they can move immediately to start gearing up to have the staff to utilize these funds. They should also be designing projects now so that they can solicit bids for the construction of those reclamation projects soon after their grant money is approved.

In addition to that, states ought to look at whether they have any large, costly AML projects for which they previously did not have enough money to complete reclamation. Those big projects could create jobs more quickly than small projects and will last longer.

I also would encourage the states to use the new authority that’s in this bill to award the reclamation contract for multiple projects in an area. That reduces the administrative costs and the overhead and provides certainty for everybody, and then the state can be working on other AML reclamation projects, designing them and getting them ready, while that larger project or multiple projects go forward.

Q: What are the steps advocates should take if they are concerned about the need to provide funding to treat acid mine drainage?

Pizarchik: I think we need to start looking at standalone legislation to provide states the freedom to use money on acid mine drainage. Don’t mandate it, give the states the choice. But where the acid mine drainage is important for a region, then they’d have the ability to do it and do it in an effective and timely fashion.

Our email tool provides a quick and easy way to contact your legislators and let them know funding for this issue is essential.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *