River Watchdogs Raise Awareness of Bacteria Levels at Popular Swim Spots

Throughout the summer months, it is typical to find the French Broad River full of families kayaking, floating and swimming in the water, cooling off from the hot sun. However, many of these families are unaware of the potential bacteria and pollution they are at risk of exposing themselves to.

A problem not unique to the French Broad, inadequate pollution spill notification systems and infrequent water testing can lead to potential health hazards to people in rivers throughout the Southeast due to exposure to certain bacterias, according to environmental organizations.

French Broad River

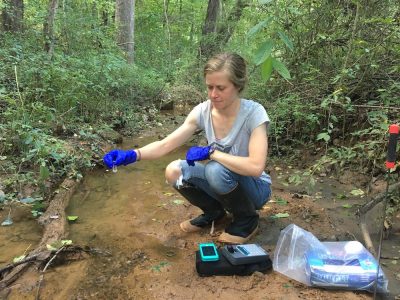

Hartwell Carson, the French Broad Riverkeeper, said that E. coli and sediments are the two largest sources of pollution in the river, which runs through Western North Carolina into East Tennessee. As riverkeeper and staff member at the environmental nonprofit MountainTrue, Carson is responsible for monitoring the river’s water quality, tracking changes in the water and eliminating pollution sources.

Some strains of E. coli bacteria, which make their way into rivers from poorly maintained sewage systems and animal agriculture, can cause health issues in people such as diarrhea and pneumonia if ingested.

Pollution levels are also exacerbated by intense storms and flooding, which Carson said have increased in recent years due to climate change.“It’s a little bit of luck of the draw if you’re out using the river that you’re not in an area that has recently had a sewage spill,” Carson says.

Those sewage spills expose people to potentially unhealthy bacterias and pollution.

People are updated about pollution spills in North Carolina through press releases and ads in newspapers, which Carson said can sometimes be posted several days after the spill has occurred.

In an effort to modernize that system, MountainTrue created a petition around 2019 asking the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality to update North Carolina’s pollution spill notification system.

“We’ve been working with the Department of Environmental Quality to take those next steps,” Carson says. “And we’re making progress. I think in the near future, as far as government time goes, we should see a statewide spill notification system.”

According to Carson, an ideal system would be some form of an online map highlighting pollution spills, as well as an opt-in email or text alert to notify people when a spill occurs.

“If the public understands the frequency and the severity of the problem, they’re going to be much more likely to support solutions to it,” says Carson. “Right now, sewage is just out of sight, out of mind. It’s underground, it goes somewhere, something happens to it and folks generally assume it doesn’t flow out into our waterways, and that’s not always true.”While North Carolina has no regulatory standard for E. coli, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency set recommended water quality standards for E. coli that were updated in 2012. These standards cannot be enforced, but act as guidelines for states.

MountainTrue’s French Broad Riverkeeper program and the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality regularly monitor the French Broad River and test bacteria levels. In both 2019 and 2020, more than half of the testing sites failed to meet the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s safe E. coli standard.

Shenandoah River

Despite similarly high E. coli levels to the French Broad River, the Shenandoah River faces problems with infrequent water testing.

In 2020, 72% of the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality’s testing sites along the river found that E. coli levels exceeded the EPA’s recommendations for safe swimming.

Tom Pelton, the director of communications for the Environmental Integrity Project, said that the Virginia Department of Health receives an EPA grant for testing ocean beaches but not freshwater beaches. The Environmental Integrity Project is a nonprofit watchdog organization that acts to enforce environmental laws at the state and national level.

Pelton stated that he views this as a classist issue, because people staying in resorts at Virginia Beach have more protections granted by the Virginia Department of Health, while families at local swimming holes in the Shenandoah Valley don’t have those protections.“I’m not saying that they’re doing it intentionally, but when you look at it on paper, residents in the Shenandoah Valley get treated like second-class citizens because they don’t know if the river is safe,” says Shenandoah Riverkeeper Mark Frondorf.

Margaret Smigo, coordinator of the Waterborne Hazards Control Programs for the Virginia Department of Health, emphasized that the commonwealth has only so much money to distribute to several competing interests in addition to water testing, such as the opioid epidemic and infrastructure improvements.

The federally funded Coastal Beach Monitoring and Notification Program implemented at the Virginia Department of Health tests 46 beach sites for bacteria weekly.

“We don’t have a complimentary funding source for a similar program to exist on fresh water,” Smigo says. “So in absence of [funding], we don’t have the ability to provide something similar. I don’t think it’s necessarily a preferential treatment on ‘wealthier beaches.’ It’s simply the fact that there is a program that exists for [saltwater].”

Water Quality in SC

The Reedy River Water Quality Group in Greenville, South Carolina is focused on limiting nutrients entering the Reedy River in order to restrict algal blooms. The group also provides water monitoring data for the river, as well as a livestream camera for people to view the group’s stream bank stabilization project.

According to Frondorf, residents and visitors of the Shenandoah should get to make the same informed decisions as people on the coastline. He would like to see the state implement more bacterial testing sites across the entire length of the river from May to September. This would be a large increase from the 25 testing sites that were on the river in 2020.

In addition to E. coli, nitrogen and phosphorus harm the river by leading to algal blooms and low oxygen zones that can be deadly to aquatic wildlife.

One solution for the pollution problem is to fence cattle away from streams. But according to Pelton, only one in five farmers were doing so as of 2019, despite the state of Virginia’s cost-share program, which reimburses costs for conservation practices including fencing projects.

Pelton adds that another reason for farmers’ reluctance to change is out of habit and custom, doing as their family members have done for generations.

“We have to tell people, ‘Just because it’s traditional doesn’t mean it’s good for the environment,’” Pelton says. “So some of it is just changing long-ingrained habits.”

In addition to these efforts, people around the world can check the status of water quality in nearby beaches and rivers through Swim Guide. This website and app gathers information from governments and environmental nonprofits about both weather and water quality for 8,000 waterfronts to provide to the public.

“A healthy environment and a healthy economy go hand-in-hand, and they’re not mutually exclusive,” says Shenandoah Riverkeeper Mark Frondorf. “They’re mutually supportive of one another. If you live in a place that has a healthy environment, people want to live there, people want to work there, people want to recreate there.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

FERC extends MVP Southgate certificate for an additional three years