Front Porch Blog

This creek, which has high conductivity and total dissolved solids, runs downstream from one of the valley fills in the Hales Gap area of Wise County. Photo by Matt Hepler

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit issued a ruling in late March upholding a district court decision that an operator cannot be held liable under the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) for a discharge that is otherwise shielded from liability by the Clean Water Act. This decision wraps up a case that started in June 2017 and was filed by Southern Appalachian Mountain Stewards, Sierra Club and Appalachian Voices. While the decision was disappointing overall, when taken as a whole, this case is still a victory for the environment and communities that live near surface coal mines in Virginia.

That’s because in September 2019, the district court that first reviewed the case ruled that mines continuing to discharge high levels of water pollution — even when active mining is complete and the mine is undergoing reclamation — must still comply with Clean Water Act regulations and SMCRA. The ruling also holds that the underdrains from surface mine valley fills — the valleys that are filled with the overburden from surface coal mines — are still considered “point sources” as they are conduits for pollution. Under the Clean Water Act, companies need a permit in order to discharge pollutants through point sources.

The mine at the center of the lawsuit is owned by Red River Coal Company, a mining corporation that operates primarily in the northern part of Wise County, Virginia. The primary complaint was about ionic pollution, a measure of all the charged particles that are dissolved in water. This ionic pollution was spreading from mountaintop removal mines to waterways through underdrains of several valley fills and was making its way into the South Fork of the Pound River without being permitted.

While the district court judge held in the September 2019 decision that the valley fills were sources of pollution, Red River was protected because of something known as the permit shield. In essence, because Red River disclosed to the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy that there would be pollution from the mine in their approved permit application and the state chose to regulate the activity under SMCRA and not the Clean Water Act, Red River was essentially protected from the lawsuit.

SMCRA also contains a provision that requires compliance with all applicable state and federal laws including state and federal water quality standards.The district court also held that the mine couldn’t be held responsible under SMCRA alone because of the Clean Water Act’s permit shield. Appalachian Voices, Southern Appalachian Mountain Stewards and Sierra Club appealed this last portion of the decision to the Fourth Circuit, arguing that the mine should be held responsible under SMCRA because of the damage to streams.

Nevertheless the implications of these cases for water coming off of surface mines in Virginia is important. It will give citizens more tools to oppose valley fills from surface mines during the water permit (or NPDES) renewals, especially if those valley fills are not already included in the NPDES permit.

Map of the Red River Mine near Pound, Virginia

How Ionic Pollution Works

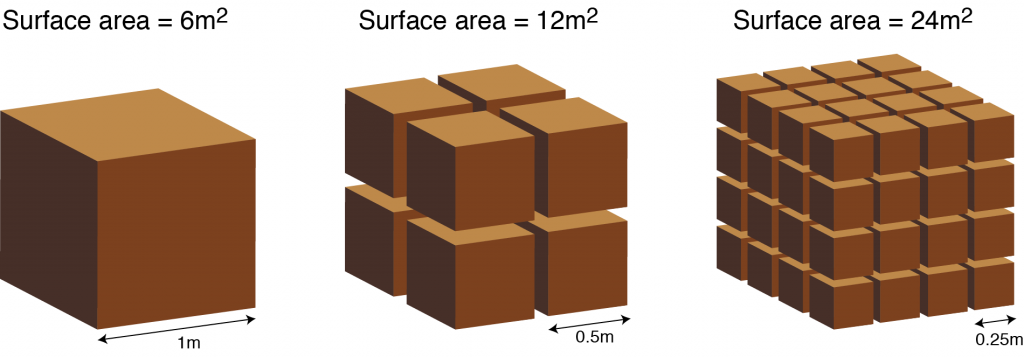

Water is known as the universal solvent because it is great at dissolving things. This largely has to do with the fact that it is a slightly polar molecule, which creates attractive forces with the other ions it comes into contact with. When mountains are blasted apart to get at the coal beneath them, the amount of surface area exposed to water increases substantially as the mountain bedrock is converted to rocks and pebbles. This gives water more opportunity to dissolve minerals, metals and salts, which causes runoff from surface mines to contain much higher levels of dissolved ions that flow into the valley streams below.

Surface area increases as particles get smaller. This allows for increased oxidation and weathering of exposed rock, leading to an increase in ionic pollution. Graphic by Jimmy Davidson

Ions are atoms or molecules in which the number of protons don’t match the number of electrons, creating a net charge. Positively charged particles are known as “cations,” and those with a negative charge are known as “anions.” Many salts, when dissolved in water, break down into cations and anions. Common anions associated with mountaintop removal mining include sulfate, carbonate and chlorine; common cations include calcium magnesium, sodium, iron and manganese. This is a non-exhaustive list, and trace elements of other salts and metals, which also dissolve into ions, can also be present. Exactly how much of each ion is present will vary by local geology.

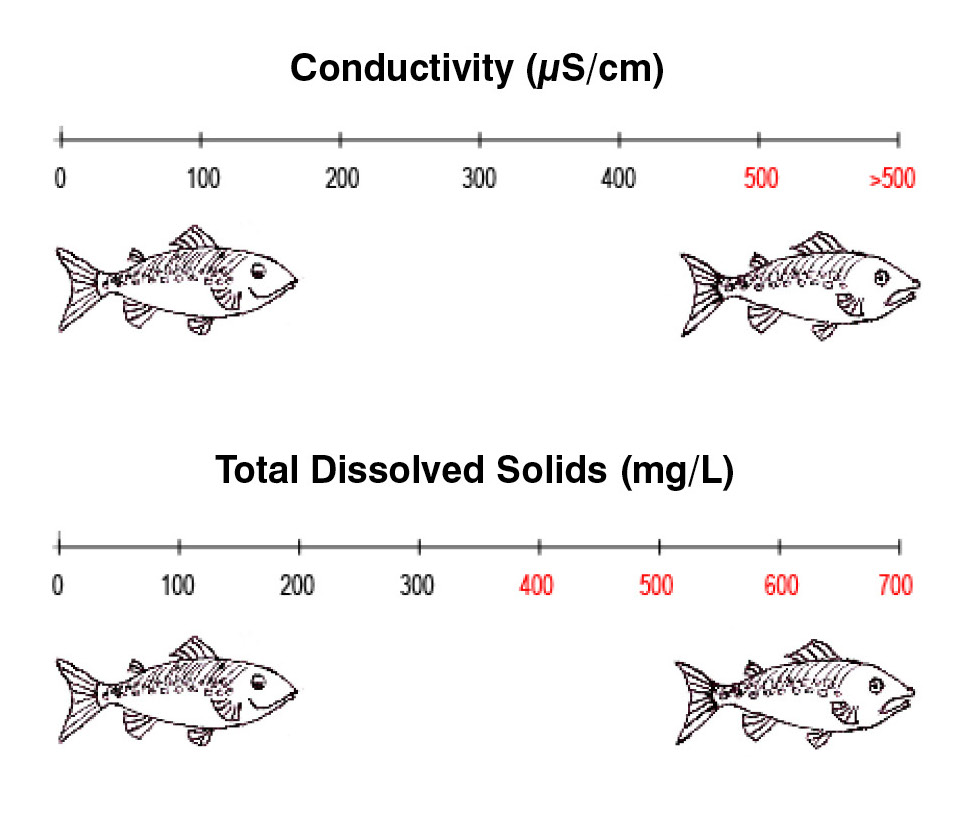

One of the most common measurements of ionic pollution is total dissolved solids, or TDS. This is a measurement of the total amount of any minerals, salts, metals or ions dissolved in water. TDS can tell us about the general quality of the water, but it does not show the chemical constituents of what has been dissolved. Technically, the units of TDS are mass divided by a volume, and TDS must be determined by processing water samples at a laboratory. But since dissolved ions carry a charge, TDS can also be estimated in the field by measuring conductivity, which is a measure of how well water conducts electrical current.

The more ions the water has dissolved in it, the better conductor it becomes, thus the higher the conductivity. TDS and conductivity measurements are proportional, with different ratios for freshwater or saltwater. According to guidance documents from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, a healthy conductivity number for Appalachian streams is approximately 300 microsiemens per centimeter and begins to decline with increases in conductivity thereafter.

The Appalachian states that monitor mining use a categorization system known as a stream condition index score to classify stream health. In the system, 100 is considered a healthy stream and zero is a dead stream. The number is calculated by collecting the small animals that live on streambeds and evaluating several key metrics of biodiversity. These include the number of stoneflies, caddisflies and mayflies found, total number of taxa, or groups of organisms, found, and the number of species found at the family level. Some families like stoneflies and mayflies are less tolerant to specific kinds of pollution, and thus their relative abundance or lack thereof can be used to detect the presence of pollutants.

Numerous peer-reviewed studies have identified an inverse relationship between increased ionic pollution and stream health; in other words, the higher the conductivity and total dissolved solids measured in streams, the lower the stream condition index score will be.

Total dissolved solids can impact aquatic life in several different ways. It can cause toxicity through increases in salinity of the water, impacts from individual ions, and general changes to the ionic composition — all of which can cause changes to the number and type of species that are present in streams. It is thought that changes in salinity impact aquatic life negatively. As streams get saltier, it becomes harder for freshwater creatures to adapt to those conditions.

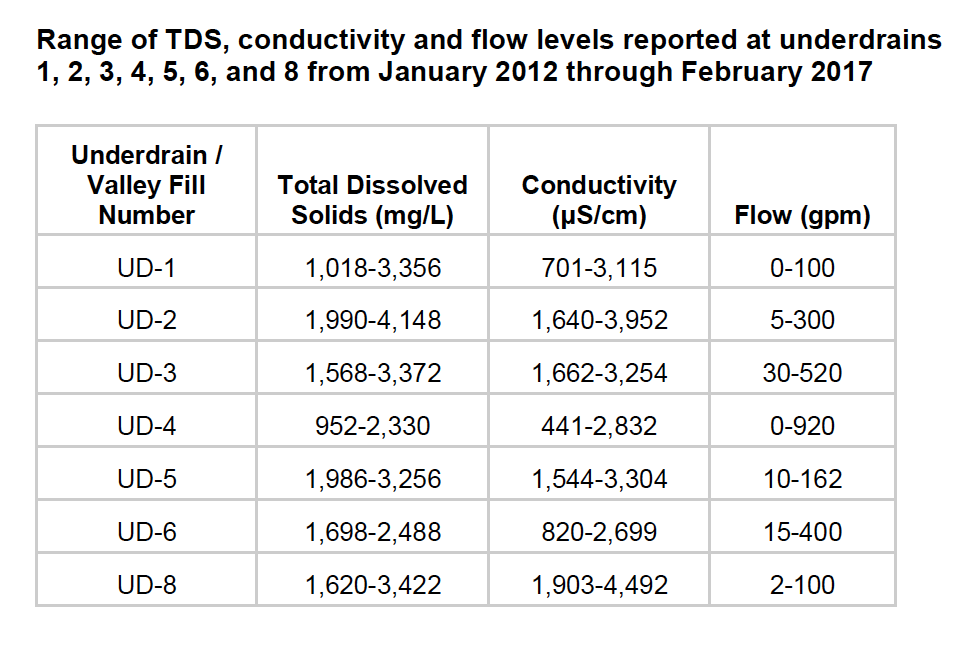

The total dissolved solids values of the original Red River complaint as measured at the toe of each of the valley fills are shown in the following table:

Water sampling revealed extremely high levels of conductivity and total dissolved solids at valley fill underdrains. Data compiled by Matt Hepler

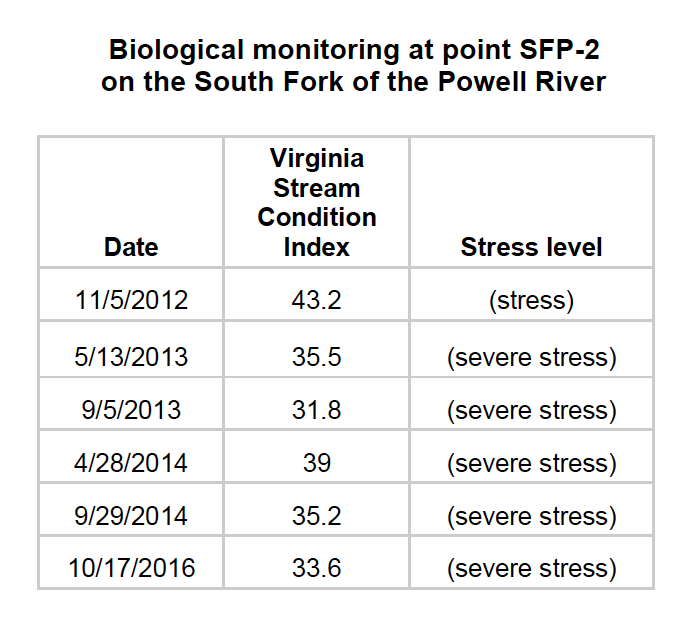

The Virginia Stream Condition Index scores are shown in the table at sampling point just downstream of the valley fills.

Biological monitoring at this point on the South Fork of the Powell River showed continuous degraded stream quality. Data compiled by Matt Hepler

As can be seen in the original complaint, the South Fork of the Powell River exhibits the same characteristics as many of the studies, demonstrating a low stream condition score as a result of ionic pollution. Because of the district court decision, which was upheld in appeals, we will be able to challenge future water pollution permit renewals (known as NPDES permits) for valley fills in order to improve the stream health in the coalfields of Southwest Virginia.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *