An Experiment in Revitalizing Old Mine Sites

True Pigments broke ground on this research-scale acid mine drainage treatment facility in Corning, Ohio, in December 2017. These tanks were moved to the Truetown Discharge site in 2020, where a full-scale AMD treatment and pigment production facility is expected to enter operation in 2023. Photo by Michelle Shively

One site near Truetown, Ohio, discharges nearly 1,000 gallons of contaminated water per minute, according to True Pigments Director of Product Development Michelle Shively. The entity is part of Rural Action, a non-governmental organization that aims to build a more just economy in Appalachian Ohio.

“Every single day, just that one discharge site puts 6,000 pounds of iron into Sunday Creek,” Shively says. “Its impact pretty much kills seven miles of stream.”

Paint pigments produced by Truetown’s acid mine drainage remediation process. Photo courtesy of Reclaiming Appalachia Coalition

Once the team showed that the process works, they worked with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources to apply for a nearly $3.5 million grant through the federal Abandoned Mine Land Pilot program to fund a full-scale facility at Truetown. In 2019, the U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement approved the grant to True Pigments. This covers about half of the project’s nearly $7.5 million price tag, and Shively is hopeful that the organization will be able to fundraise the remainder and have the facility in operation by early 2023.

“Having this money allocated does give our project a lot of credibility because we have this much support already,” Shively says.

The goal of the AML Pilot program is to fund economic development near old, abandoned coal sites like Sunday Creek. But the complicated approval process between states and the U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement can cause long waiting periods to receive the grants. And in some cases, a lack of transparency and consideration of community input has led to grants for questionable projects.

True Pigments aims to have the facility operational at the Truetown discharge site by 2024. Apart from several dozen temporary construction jobs, Shively estimates that the facility will employ four to six people.

“There’s a huge market for iron oxide pigment in the U.S.,” Shively says. “Currently, almost 80 percent of the iron oxide in this country is imported.”

Rural Action’s projections show that the plant would produce 0.5 percent of the country’s consumption of iron oxide, and that the chemical compound could be used for industrial-grade colorings as well as artist-grade paints. Shively states that the profits from selling the reclaimed iron oxide will pay for the plant’s operation and could fund future watershed restoration projects like this one.

“Thinking about the potential for replication of this technology across Appalachia, a lot of our neighbor states have a lot of these large discharges as well, and some of the states are currently spending a lot of money on an annual basis to operate treatment systems,” Shively says.

“It really feels good to change this story and do something that can be a steady economic presence in former coal areas,” she adds.

AML Pilot Process

Rural Action is part of the Reclaiming Appalachia Coalition, a multi-state network that promotes innovative mine reclamation projects. Appalachian Voices, the nonprofit organization that produces The Appalachian Voice, is also part of the coalition. In January, the RAC released their third annual report highlighting creative AML Pilot projects and proposals in Appalachia. Downstream Strategies, an independent consulting firm that contracts with the coalition, conducts economic analyses for these projects.The AML Pilot program is an offshoot of the federal Abandoned Mine Lands program, which was created under a 1977 surface mining law that requires companies to pay a per-ton fee toward the AML fund. The Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement then distributes annual payments from this fund to states and tribes to remediate mines that companies abandoned before the 1977 law went into effect.

“Cleaning up mine sites can improve both surface water and groundwater, which has clear environmental and economic benefits,” Appalachian Voices Legislative Director Thom Kay said in May 2017 testimony before the U.S. House Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources. “Along with creating immediate reclamation jobs and drawing tourism through improving the land and protecting fish and wildlife, cleaning up mining pollution can help improve the health of communities.”

According to the OSMRE, there is approximately $2.3 billion left in the fund — but at least $9.7 billion in known abandoned mine cleanup costs. This sum does not account for lower-priority sites or more recently identified sites, so the actual cost is likely vastly higher. The fee that supports the traditional AML program is scheduled to expire in September 2021, and the Reclaiming Appalachia Coalition supports reauthorizing that funding mechanism for the AML program.

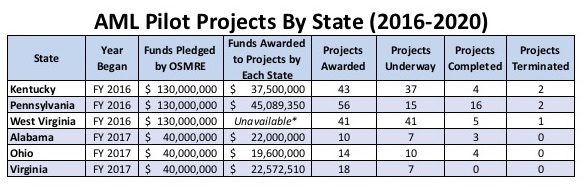

Congress created the AML Pilot program in 2016 after repeated calls to accelerate Appalachian mine remediation while supporting economic development efforts in transitioning communities. Since then, legislators have allocated $665 million from the U.S. Treasury, not the AML fund, to six states and three tribes through the AML Pilot program.

Data is current as of January 2021.Sources: AL Dept. of Labor; KY Energy and Environment Cabinet; OH Dept. of Natural Resources; PA Dept. of Environmental Protection; VA Dept. of Mines, Minerals and Energy; WV Dept. of Environmental Protection *West Virginia did not provide data on how much had been spent

The AML Pilot program is similar to the RECLAIM Act, a bill supported by Appalachian Voices and others that, if passed, would accelerate the distribution of $1 billion from the AML fund to states and tribes for projects that involve both mine reclamation and economic development. The U.S. House of Representatives passed the bill in July 2020, and the bill’s sponsors in the new Congress are expected to introduce it in the coming weeks.

But there are a few key differences. While the AML Pilot program encourages but does not require community input before allocating funding, the RECLAIM Act would mandate a process for public engagement before funds are released. And while projects under the pilot program frequently include environmental remediation, they are not required to, whereas mine land remediation would always be required for projects funded by the RECLAIM Act.

“Legislators often say they want to help revive rural working communities, and the RECLAIM Act is an opportunity to do just that,” says Kay. “While we support continued funding for the AML Pilot Program, its shortcomings relative to the RECLAIM Act are another reason Congress needs to pass the bill.”

Under the AML Pilot program currently, once Congress allocates the money to states and tribes it can often be up to two years between the time grantees apply for funds and receive them. After a project is approved by the state, it gets sent to OSMRE for approval. If the federal agency approves it, then the state or tribe has to gather information for OSMRE to complete an analysis under the National Environmental Policy Act. If OSMRE finds no issues, then the agency releases the funds to the state. Opportunities for obstacles abound.

“We had to do a number of fairly significant revisions,” Mark Moormans of nonprofit community action agency People Inc. of an AML Pilot grant application.

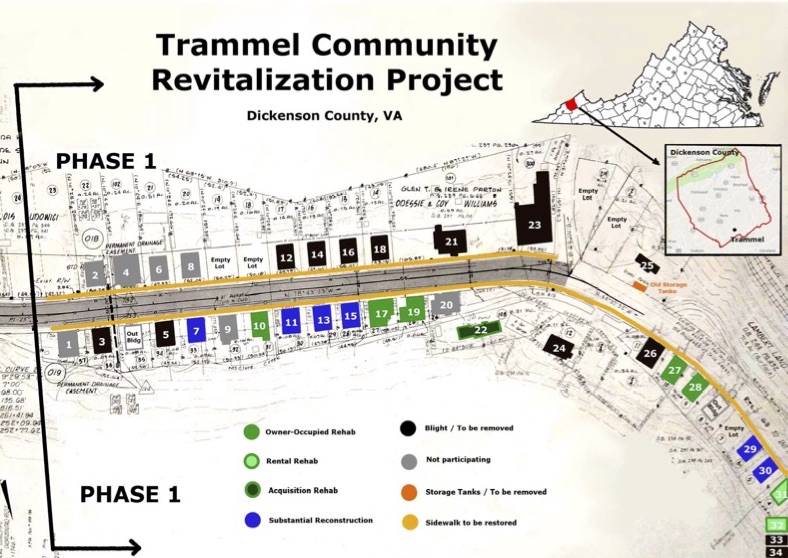

The group is leading a project to revitalize the community of Trammel, Virginia, which was founded as a coal camp in 1918. The project includes rehabilitating old homes, demolishing run-down buildings, repairing sidewalks and mitigating road and drainage issues. Although the project also included remediating a partially open mine portal, that was eventually removed from the project scope in one of the application revisions. For the environmental side of the project, Moormans states that they worked with a number of state and federal agencies. Downstream Strategies conducted economic analyses for the project.

Phase one of the Trammel community revitalization AML Pilot project. Photo courtesy of Reclaiming Appalachia Coalition

“[The] DMME really went out of their way to try to help coach us,” Moormans says.

Moormans underscored how vital the DMME’s feedback was to People Inc. receiving funding. In light of OSMRE’s concerns about the potential for significant, ongoing administrative overhead, the DMME eventually directed the organization to not use the AML Pilot funding on housing rehabilitation that benefits specific households. Instead, the AML Pilot funds are set to be used for community-wide aspects such as blight removal and broadband internet expansion.

“We are extremely grateful for the funds, even though it took a lot more time than we thought it would to get to where we are,” says Moormans

While Moormans had hoped to complete the first phase of the project by early 2021, delays caused by COVID-19 have pushed projections back to later in the year at the earliest.

More Complications

After the funds are approved, other difficulties can arise.

“You’re funded before you actually have the project fully designed, because part of the money is to actually design the project itself. That’s a pretty substantial expense,” says Appalachian Conservation Corps Director Zach Foster.

His nonprofit organization works with public land managers on projects that benefit local economies and the environment. One of these projects is improving the Devil’s Fork Loop Trail in Scott County, Virginia. Other project partners include the U.S. Forest Service, Friends of Southwest Virginia, Scott County and Appalachian Voices, with economic analysis provided by Downstream Strategies.

The Devil’s Fork Loop Trail leads to the Devil’s Bathtub natural pool in the Jefferson National Forest. Photo by Jimmy Davidson

Soon after the Devil’s Fork project received funding, however, the Forest Service told organizers that the entire proposal needed to be redone due to erosion problems on the trail.

The team has since restructured the project and is back on track. Foster stated that they are currently working through administrative and compliance measures, which are made difficult due to COVID-19 restrictions.

“These pilot projects are really complex in that they have several community groups coming together to do the work,” Foster says. “We can’t be in the same space and actually see the project on the ground, and perhaps that’s slowing down things a bit.

“We’re bringing in several different federal agencies and state agencies,” he continues. “And so it just takes time to navigate those layers. But the folks at the DMME have been awesome in terms of setting up a really clear timeline, providing a ton of technical support and then even providing resources.”

Community Engagement

For small, community-led projects, it can be difficult to navigate the AML Pilot grant process.

“In some ways, these larger engineering firms working on AML Pilot projects have it easier because they’re all one cohesive unit,” says Appalachian Voices Central Appalachian Environmental Scientist Matt Hepler. “If you’re a community group doing an AML Pilot project, it’s a lot harder to have to go through processes like the selection process for contractors. Those little things add up over time.”

The community of Dante, Va., is building a walking and biking path and an ATV trail with AML Pilot funds. Photo by Kevin Ridder

[Read more about Revitalizing Dante]

Hepler states that the team behind the Dante project is currently working on completing a National Environmental Policy Act analysis. Despite the long time period it can take to receive AML Pilot funds, he believes that it is worth it.

“It should be expected to take longer than some of the larger projects,” Hepler says.

In Ohio, Rural Action conducts public engagement for the state’s AML Pilot program by identifying project areas and helping communities prepare applications.

“[The state AML Pilot program] knew that they needed assistance in public engagement, and we’ve been able to assist them there,” says Rural Action project manager and former head of the Ohio AML Pilot program Terry Van Offeren. “So it’s been a nice symbiotic relationship.”

The 120-foot-long King’s Hollow Tunnel would be part of the Moonville Rail Trail once completed. Photo courtesy of Reclaiming Appalachia Coalition

The nonprofit Moonville Rail Trail Association has been developing the trail since 2001, and has acquired several other grants in addition to the AML Pilot funds. The estimated completion date for the project is June 2021, according to Van Offeren. Throughout the AML Pilot application process, Van Offeren states that Rural Action met with county governments, cottage industry representatives, a bike sales and rental shop and more.

Economic modeling conducted by consulting firm Downstream Strategies projects an economic benefit of nearly $22 million and 236 jobs after construction is complete and the trail has been in operation for one year.

Expanding Access

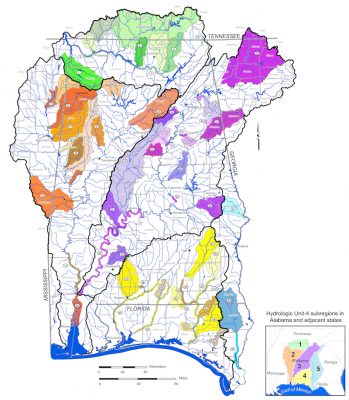

To help more groups access the AML Pilot program, the Reclaiming Appalachia Coalition awarded $35,000 in mini-grants, plus technical assistance from Downstream Strategies worth $15,000, to five community-led projects in 2020. One of the grant recipients was the Cawaco Resource Conservation & Development Council, a non-governmental organization in central Alabama.

This map, created using Reclaiming Appalachia Coalition mini-grant funds, shows abandoned mine sites that overlap with important wildlife habitat. Photo courtesy of H2O Alabama Rivers and Streams Network

Johnston states that getting funds from the AML Pilot program for the North Fork Creek project wasn’t on their radar before talking with the coalition. Traditionally, Alabama’s AML Pilot program focused on hazard mitigation above other concerns.

“We didn’t really have the opportunity to partner [with the AML Pilot program] because we both had different goals,” Johnston says of past years. “This is the first year where they’ve added water quality as a priority.”With the data obtained through the mini-grant, Johnston states that Cawaco has further capacity to identify and implement meaningful projects for AML Pilot program consideration.

“We will be the first in the state to apply for one of these grants,” she says. “And that is a direct result of Appalachian Voices and the Reclaiming Appalachia group.”

Transparency Troubles

Some state AML Pilot programs are more transparent to the public than others.

In Virginia, the DMME developed a rubric for grant applicants to give people an idea of what the agency looks for in projects. Additionally, the DMME meets with potential applicants to discuss project concepts. And in Ohio, the state AML Pilot program contracts with Rural Action to conduct extensive public outreach for community-based projects in Southeastern Ohio.

Downstream Strategies Senior Strategist Joey James states that most AML Pilot projects in West Virginia lack mine remediation and reclamation components. Additionally, the Mountain State disproportionately invests AML Pilot funds in basic water and sewer projects. In an email, James wrote that there is a “blatant lack of transparency in the award decision-making process.”

And in Kentucky, the state’s efforts to involve community input in the AML Pilot program have been historically lacking, according to Rebbecca Shelton, coordinator of policy and organizing with the nonprofit law firm and former Reclaiming Appalachia Coalition partner Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center.

“Over the last few years, we’ve been pretty disappointed by Kentucky’s level of commitment to community engagement around the AML Pilot program and the lack of information about funded projects,” Shelton says. “It’s just all been pretty veiled.”

Shelton explains that the state’s website was not updated regularly for the first three years of Kentucky’s AML Pilot program. Most of the information about what projects were funded came from sporadic press releases and annual OSMRE reports. She adds that the communication between the state and OSMRE is done outside of the public eye.

“It was not a lot of commitment to letting the public know about the opportunity, which was really frustrating for us,” Shelton says.

Some of those early projects were given millions of dollars, and the results are still unknown.

In November 2016, then-Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin and U.S. Rep. Hal Rogers (R-Ky.) announced a $12.5 million AML Pilot grant for the Appalachian Wildlife Center in Bell County, Kentucky. The proposal included a visitor center with a museum and theater, trails and a nature preserve on 12,000 acres of former mine land with an opening date of 2019.

When applying for the grant, the Appalachian Wildlife Foundation, which is behind the center, projected the creation of more than 2,000 jobs, an annual visitation rate of 638,400 people per year and a cumulative economic impact of more than $440 million by 2023. The foundation’s website states that these numbers are based on models utilized by the U.S. Department of Commerce and attendance statistics from the Elk Country Visitor Center in Benezette, Pennsylvania.Four years later, the wildlife center’s thousands of projected jobs and influx of tourism dollars have not yet materialized for Bell County. Appalachian Wildlife Foundation Chair Frank Allen expects that the center will open in May 2023.

“We expected it to be done in 2019; we’ve learned a lot since then,” Allen says. “The process, doing it as a nonprofit organization, has been brutal.”

Regardless of the delay, Allen states that the foundation has managed to raise the rest of the money for the project.

“We’re probably one-fifth of the way there if you measure it in dollars,” Allen says. “It’s going to be about a $55 million project, and we’ve already spent $11 million on infrastructure.”

Appalachian Wildlife Foundation CEO David Ledford told the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting in October that construction challenges on the former mine land, an environmental assessment and COVID-19 caused the delays. According to KYCIR, state officials were also unable to show that the job and tourism projections had been independently vetted.

Allen disputes the notion that the project was not properly evaluated, stating that “outside consulting firms” vetted the projections and emphasizing that three government agencies approved the project.

“It’s not like these are a secret forecast,” Allen says. “They were presented with all of our grant applications and funding and, you know, they are what we believe they will be, and time will prove us right or wrong.”

“We believe our numbers are going to be far higher than anything anyone else has said,” he adds.

The center is not the only behind-schedule project in Kentucky. In 2019, officials allocated $3.37 million in AML Pilot funds for new infrastructure and renovations at the Eastern Kentucky Business Park in Martin County. The park still sits mostly vacant, however, in a county with consistent water problems and a poverty rate of approximately 34 percent, according to 2019 Census data.

In fact, the state has pledged nearly $26 million in AML Pilot funds to this park and three other Eastern Kentucky industrial parks since 2016, according to KYCIR. The publication states that the remote parks remained mostly empty as of late 2020.

And in 2018, Kentucky pledged $6 million in AML Pilot funds to Enerblu, Inc., to build a battery manufacturing plant in a Pikeville industrial park that would supposedly bring more than 900 jobs. The state also awarded $4.5 million that year for water infrastructure at a planned federal prison in Roxana, Kentucky, that would employ approximately 300 staff.

But in 2019, Enerblu canceled the project and filed for bankruptcy. According to Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet spokesperson John Mura, no AML Pilot funds were given to the company. Instead, approximately $293,000 of AML Pilot money went to the City of Pikeville for architectural and construction management services. Mura stated that instead of having the money returned, the already paid-for work was retrofitted to accommodate a future business on location at the same industrial park.

As for the proposed Letcher County prison, the U.S Bureau of Prisons withdrew plans to build the facility in 2019 after advocacy groups and prisoners filed a federal lawsuit over the project’s environmental impact and the lack of public input on the prison.

Zach Foster with the Devil’s Fork project emphasizes the importance of community input during the AML Pilot grant application process, an element that would be enshrined in law if the RECLAIM Act passes.

“Communities need to have a really strong voice in this process because these projects are going to be really impactful on the community,” Foster says. “Communities know what needs to get done to make the changes they want to see. It also builds investment, because this is really hard work to get this done and it’s not a simple process. And so you need folks who are invested and understand that this is often a multi-year effort.”

Changes to Kentucky’s AML Pilot Program

Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet Spokesperson John Mura states that the cabinet has improved transparency surrounding the program since Gov. Andy Beshear’s election in 2019.

“During the Beshear administration, the application process became much more transparent through web access, better application documents, and regional workshops conducted for interested applicants,” wrote Mura in a January email. “This resulted in a record number of applications and record high funding request[s] for the 2020 application year.”

He also stated via email that, “Applications with the greatest potential for economic impact to the region, with commitment from community and business partners, and that demonstrate long term self-sufficiency are given priority. Also encouraged are projects that can be completed in a timely fashion, encourage significant tourism, retrain displaced coal miners, or provide water, sewer or gas infrastructure to industrial areas.”

Mura wrote that the cabinet has the ability to suspend additional funding and revoke AML Pilot grants if project partners do not comply with program guidelines.

“Applicants are heavily encouraged to conduct outreach to community members for their input and support before submitting proposals,” he added. “[EEC Secretary Rebecca Goodman] consults with industry and governmental leaders, reviews and then selects applications for submission to OSMRE for the federal vetting process.”

Shelton states that while these changes have helped, the decision-making process for AML Pilot grants in Kentucky is still murky.

“I also think it is essential to value commitment from the community for a proposed project as an important criteria for a project’s success, but how important is this criteria in comparison to the others? And is the support of some community members more important than others?” Shelton asks.

“Some projects with several endorsements have not been funded and some projects with few or no endorsements have been funded. In addition, in the past, there has been active community opposition to a project such as providing funding for a water line and treatment facility that would expand the capacity of a federal prison in Roxana, Kentucky. But that project was still funded.”

Rebecca Shelton states that it will likely be some time before impacts of AML Pilot projects are felt.

“Part of the challenge with this program is it takes a really long time for these projects to get off the ground,” she says. “There are just a lot of layers of approval and different assessments that have to be done.

“I think in the next year we should have a better sense of what the real impact of some of that money spent has been.”

To learn more about RECLAIM Act, visit ReclaimAct.com. Find more information about the Abandoned Mine Land Pilot program and other funding sources for mine land reclamation at ReclaimingAppalachia.org.

This story is the first of a two-part series examining the impact of Abandoned Mine Land Pilot program funding in Central Appalachia. Look for the second installment later this spring. Got a tip for our writers? Drop us a line at voice@appvoices.org or call (828) 262-1500 ext. 5.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Tennessee Drafting Public Recreation Plan