The interior of Taylor Prince’s tiny house has paneling made from repurposed floorboards. Photo by Taylor Prince

In the soft mountains of Sugar Grove, N.C., Ingrid Forsyth and Ezra Knight live with their cat, Yin, in a 128-square-foot tiny home they built for $11,000. The house has just enough room for a kitchenette, lofted bed, built-in loveseat and a fold-down table. The bathroom is one of the couple’s favorite features, boasting a regular-sized shower they tiled with found terra cotta and an $800 composting toilet, which surpasses the sophistication of a bucket only by its ability to separate No. 1 from No. 2.

Knight and Forsyth adore their space. They excitedly point out the beautiful kitchen cabinets made from repurposed chestnut they painstakingly refinished themselves. Knight recalls with a satisfied expression how time-consuming the tongue and groove walls were, and how fun installing the solar system was. Throughout their tiny abode, small artistic touches, like the loft ladder made from local rhododendron branches, add even more charm to a space clearly built with love.

The couple’s home is a perfect example of a do-it-yourself “Tiny House on Wheels,” a noticeable trend in American housing. Whether it’s a fad or a movement remains to be seen, but there is no doubt that “tiny houses” have become an increasingly popular housing choice since the early 2000s.

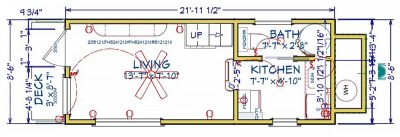

Only an hour away in the valley of Triplett, N.C, I’m constructing my own tiny house on wheels. At 220 square feet it will have more room than the Sugar Grove Tiny, and also probably cost a few thousand dollars more in materials. Like Knight and Forsyth, I get excited and dreamy-eyed when I talk about my house, named Full Moon Tiny after the small-scale, organic Full Moon Farm on which it currently lives.

Not all tiny houses are on wheels, but they are all quite small, between 100 and 400 square feet, whereas the typical American home is about 2,600 square feet. These days, there are a myriad of small, local companies selling a wide variety of tiny homes, ranging from just a shell for DIY-ers to luxury abodes costing upwards of $110,000.

Although the average American home has steadily increased in size over time, all across the country thousands of tiny houses are popping up as more and more people downsize their lives and their footprint.

In “The Small House Book,” tiny house pioneer Jay Shafer argues that these trends are partly due to minimum size requirements, which local governments began writing into housing codes in the ‘70s and ‘80s. These requirements, Schaffer claims, have led to larger, more expensive homes. Heavily influenced by developers, banks and the housing industry, housing codes often make it illegal for Americans to live in tiny, off-grid dwellings.

The tiny house movement is, in some ways, a response to this. Forsyth and Knight’s home is smaller than the 260 square feet of habitable space that North Carolina requires for two people. But because their home is on a trailer, they can register it as an RV and bypass many of their state’s housing codes — including the prohibition of composting toilets and repurposed lumber.

Tiny home owners are asked all the time, why not just get an RV? But, unlike RVs, tiny homes can have all the amenities of a normal house and are built with quality materials that keep them warmer and more breathable than a camper.

“RV’s are for everyone, and in a way made for no one,” says Taylor Prince, who owns a 212-square-foot tiny house he built with local Mennonite barn builders in Oak Springs, Tenn. “We built our house around what we had and needed. They even measured my shoulders for the doorways!”

Plus, a new state-of-the-art camper costs about $90,000 compared to Prince’s custom tiny house, which cost him $45,000.

Tiny is Green

Tiny houses literally have a smaller footprint, but they also use far fewer resources during construction than typical American homes. I was very pleased to only create a single bag of waste constructing the entire shell of my tiny house. Building an average American house, on the other hand, produces seven tons of construction waste, according to Shafer, and uses almost an acre of forest!

The author stands with her tiny house while working on the plywood sheathing. Photo courtesy of Sarah Kellogg

With such a small space, builders can afford the extra cost of sustainably sourced materials, high-quality insulation, LED lights and energy-saving appliances. They also often use recycled lumber such as barnwood and other second-hand building materials like windows. Many folks design their tiny homes to be completely self-sufficient, utilizing composting toilets and solar energy systems.

Due to their small size and efficiency, tiny houses use relatively little in the way of electricity and fuel. A report commissioned by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality found that “reducing home size by 50 percent results in a projected 36 percent reduction in lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions.” The average tiny home is 90 percent smaller than the average American house, meaning a 65 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

Finances and Freedom

Like me, Forsyth and Knight wanted to build a tiny house because it seemed like the most achievable way to own a home. Sick of paying rent and wary of debt, Forsyth recalls, “I was really passionate about sustainable, regenerative, off-grid living, and I saw that the only way to delve into that, especially given the amount of money we had, would be to build a tiny structure.”

“It’s incredibly liberating to not have a mortgage,” Prince notes. “I didn’t have to go to a bank to build a structure and I’m able to adapt if I’m thrown a curveball.”

Not only are tiny houses a response to building codes and an effort to live more sustainably, they’re also a response to the affordable housing crisis in America. For this reason, the tiny house trend may indeed be a movement and not just a fad.

“I legitimately thought it was going to be a fad,” reflects Prince, “as in, over as soon as it started. But wages aren’t exactly going up and housing availability isn’t exactly getting better either, so it seems kind of like a natural alternative for folks struggling to find a comfortable space to live.”

Tiny Homes, Big Community

Throughout the process of building my tiny house, I’ve met so many great people. I’ve learned to ask for help when I need it. I’ve borrowed tools and I’ve lent them. In a sense, I’ve started to build a community through my tiny house project that I wouldn’t have otherwise had.

Prince was drawn to a tiny home because he wanted to change his life, to get rid of the stuff he didn’t need and the large empty rooms he never used.

“There’s an emotional and social aspect to it,” Prince says. “Now I want to start creating more common spaces where people can share their belongings and have access to other people’s stuff if they’re willing. So, you have your living space but the community has additional places to meet your material needs. Not everything has to be on your own private property.”

For Forsyth and Knight, living tiny means opening up the lines of communication. “There’s no room to go hide and smolder in,” Knight reflects, “we have to communicate.” Forsyth agrees, noting, “we have to be careful what energies we bring into such a small space. But my favorite part of living in the house is the sense of togetherness that both challenges and strengthens our relationship!”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

2 responses to “The Tiny House Revolution”

-

What is the smallest size truck or Sedan you could use to move the house?

-

I would love to see more tiny house designs,in future issues, and wonder how it is to move such a house. Also wondering how sturdy they are when they are on the road, and how much gas or drag do they incur.

Leave a Comment