Front Porch Blog

Special to the Front Porch: Our guest today is Cathy Kunkel, an energy analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, and lead author of a new report on the overbuilding of natural gas pipelines in the mid-Atlantic. Kunkel has undergraduate and master’s degrees in physics, was a senior research associate at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and has testified before regulatory bodies.

We’ve published a report today that concludes that two natural gas pipelines proposed for construction from West Virginia into Virginia and North Carolina are indicative of a rush toward industry overbuilding.

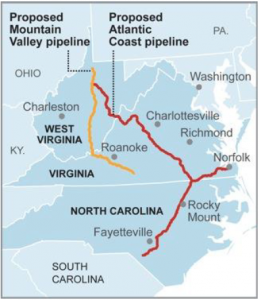

The study, “Risks Associated With Natural Gas Pipeline Expansion Across Appalachia,” examines the proposed Mountain Valley Pipeline, which would traverse West Virginia into eastern Virginia, and the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline, which would cross Virginia and branch deeply into North Carolina. The pipelines combined would run for more than 800 miles and together would cost roughly $9 billion.

There’s a widespread assumption that such pipelines would only be proposed if they were necessary. This assumption is not supported by the facts.

We found that the dynamics of the pipeline business tend toward overbuilding, toward building excess pipeline capacity. Major pipeline companies are competing with each other to build out the best, most well-connected pipeline networks. And utility companies are entering the pipeline space because much of the risk of overbuilding can be pushed off onto captive ratepayers. And natural gas production companies are entering the pipeline business because their core business — drilling — is underperforming and they are looking for ways to boost revenue and investment value. These kinds of financial considerations on the part of individual companies do not add up to socially rational, prudent long-term planning.

The pipeline business is able to attract more capital than is needed—because of the high rates of return that pipeline companies typically earn. Pipeline rates are regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). FERC allows higher rates of return for pipeline companies than it does for electric transmission companies or than state utility commissions typically allow for state-regulated utilities. For example, by policy FERC allows a 14 percent rate of return, while regulated utilities at state public service commissions typically are only allowed in the 10 percent range.

The pipeline business is able to attract more capital than is needed—because of the high rates of return that pipeline companies typically earn. Pipeline rates are regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). FERC allows higher rates of return for pipeline companies than it does for electric transmission companies or than state utility commissions typically allow for state-regulated utilities. For example, by policy FERC allows a 14 percent rate of return, while regulated utilities at state public service commissions typically are only allowed in the 10 percent range.

The tendency towards overbuilding is widely understood in the industry -— executives and analysts talk openly about it -— and FERC’s regulatory process currently misses this dynamic. There is no regional planning process for natural gas pipeline infrastructure in the way that there is for electric transmission lines, for example. FERC looks at pipelines on a project-by-project basis. The agency considers a line necessary if the project developer is able to enter into contracts for the majority of the capacity of the project. What we’ve found in the Atlantic Coast and Mountain Valley Pipeline cases is that the project developers and the shippers who are entering into contracts with the pipeline are subsidiaries of the same company. So the fact that a pipeline developer is signing a contract with an affiliate is strong evidence that there is financial advantage to the parent company from building the pipeline, but not necessarily that there is an independently established basis for the pipeline need. The private assumptions of individual pipeline developers are not adequately checked against broader standards of the public interest.

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline is a good example of this. If it is approved it appears that two separate pipelines will serve the same power plant -– an example of too much pipeline capacity. The Atlantic Coast project is a joint venture with Duke, Dominion, Piedmont Natural Gas and AGL Resources having ownership interests and are the developers. The main shippers on the project are subsidiaries of Duke and Dominion — those two companies have contracted for 68 percent of the capacity on the pipeline. Consumers will bear the risk of higher rates if project assumptions do not materialize. The cost of building the pipeline, including the profit for the developers, will be passed through to the shippers of the pipeline who will be able to recover it from their ratepayers through rates established by state public service commissions.

Put another way, the regulatory structure gives Duke and Dominion an incentive to prioritize building their own pipeline rather than using that of another company. If the demand for the capacity along the Atlantic Coast pipeline does not materialize, ratepayers will still be on the hook to pay for that capacity.

It appears that the need for the Atlantic Coast pipeline has been overstated. In its application to FERC, Atlantic Coast asserts that one use of the gas from the pipeline will be for Dominion’s new Brunswick and Greensville natural gas plants. But in its applications to the State Corporation Commission to build those power plants, Dominion asserted that the plants will be fueled from the Transco line. In the case of the Brunswick plant, a spur from the Transco line to the plant has already been built. Without better coordination and planning it appears that two pipelines are being built to supply one power plant. The Atlantic Coast pipeline is a relatively low risk venture for Duke and Dominion, the main project developers. Most of the risk for the project is borne by those utility customers in Virginia and North Carolina.

The Mountain Valley Pipeline has a different risk profile. The Mountain Valley pipeline is a supplier-driven pipeline. The majority-owner of the project is an affiliate of EQT, one of the largest Appalachian shale gas drillers, and the entity that has contracted to ship the largest volume of gas on the pipeline is EQT. We found that the biggest risks of this project stem from the financial weakness of EQT. EQT is not doing badly relative to other Appalachian shale drillers, but the entire sector is in turmoil because of sustained low natural gas prices, which are widely expected to remain low into 2017. EQT’s credit ratings are one notch above junk, and its stock has fallen 26 percent since January 2014. Bankruptcies are widely expected in the natural gas drilling sector this year, and banks are expected to cut back on lending. EQT has diversified into the pipeline business presumably because of the traditionally stable and higher returns to be found in this sector.

Communities along the pipeline route also bear risks that stem from EQT’s financial weakness. EQT does not appear to be a stable, long-term partner for these communities. EQT’s weakened financial position suggests it will adopt only a limited commitment to communities or perhaps be forced to sell its ownership interests to a new company that is not part of current deliberations

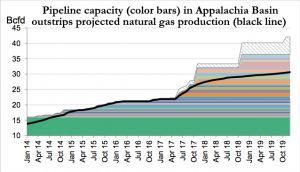

To sum up, our study finds that natural gas pipeline infrastructure out of the Marcellus and Utica regions will become overbuilt within the next several years, an outcome recognized by many in the industry itself.

The economic and financial factors that incentivize companies to invest in the development of new natural gas pipelines will not produce a socially rational outcome. Without a coordinated approach to natural gas pipeline planning, as exists for many other types of infrastructure, the FERC cannot make an honest determination of the need for these pipelines. Ratepayers and communities will shoulder much of the costs and risks of the Atlantic Coast and Mountain Valley pipelines, investments of nearly $9 billion that are poised for approval without adequate scrutiny.

Stay informed by subscribing to the Front Porch Blog.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *