Digging Under the Surface: West Virginia’s Fracking Boom

By Kimber Ray

When West Virginia landowners agreed to sever the right to use their land from their rights to the minerals buried beneath the surface, they never imagined the sweeping changes this could impose on the landscape of their communities.

A gas drilling rig was built on David Wentz’s land in Doddridge County, W. Va., without his permission, a legal phenomenon that is increasingly widespread in areas such as the Marcellus shale region. Photo by Diane Pitcock, wvhostfarms.org

This separation of land and mineral rights, known as a “split estate,” is permitted throughout the United States, but the prevalence of such contracts widely varies. Many of these agreements were negotiated while drilling rigs were still powered by horses or steam.

“[Drilling operators] take old leases — I’ve seen them from 1890, 1906 — and the wording in it will say ‘For as long as the well is in production, this lease maintains force,’ and that they can come back to drill additional wells,” explains Diane Pitcock, a local resident who moved to Doddridge County, W.Va. in 2005.

State laws governing whether homebuyers must be made aware of split estates are rare since, until recently, it was generally not considered an important issue.

Yet today, previously quiet, rural communities across West Virginia have watched concrete well pads come to dominate ridgetops above once-secluded homes. Long convoys of heavy trucks and trailers pulverize county roads. Networks of pipelines cut through forested lands to carry billions of cubic feet of Marcellus shale gas to neighboring markets each day.

Of the active Marcellus states — including West Virginia, eastern Ohio, and Pennsylvania — only West Virginia requires landowner compensation for surface damages, but companies are given broad freedom to determine what that payment should be. Mineral rights holders are entitled to “reasonable access” to their resources, a claim that often trumps the rights of homeowners. None of these states require compensation for subsequent air and water pollution, however, and companies have historically denied responsibility.

After witnessing the destructive impact of split estates on some of her neighbors, Pitcock decided to forgo her planned retirement and, four years ago, she founded the grassroots network West Virginia Host Farms. The program invites concerned landowners to help promote increased research and reporting on Marcellus shale drilling in West Virginia which, according to Pitcock, started to occur more intensively two years ago.

Beth Crowder and David Wentz are among many landowners who experienced this first-hand at their 300-acre property in Doddridge County, W. Va., which is known as a “sweet spot” of the recent Marcellus shale gas boom.

When the gas company announced that 37 acres of the Crowder and Wentz property had been sited for a Marcellus shale well pad, the company did not need their permission because neither of the two owns their land’s mineral rights.

“The first opening salvo you’ll get is somebody contacting you about a surveyor,” explains Crowder. “Maybe they’ll come to your property soon, or maybe never.”

Bucking Convention

Drilling and hydraulic fracturing are nothing new in West Virginia, but the process has long been dominated by vertical, or conventional, wells that tap into easily accessed pockets of oil and natural gas. More than 59,000 such wells are scattered across West Virginia today, according to the nonprofit FracTracker Alliance. Production from these conventional reservoirs peaked by 1920 for most of Appalachia.

Yet geologists had long known of the production potential from more hard-to-reach reservoirs such as shale gas. The two drilling techniques that would come to be known as fracking — hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling — were both developed in West Virginia decades before the first Marcellus shale gas well was drilled. But fracking remained largely unheard of until 2004, when improved computer technology and high natural gas prices set the shale boom in motion.

The large number of trucks needed to support drilling operations results n road damage and frequent accidents. Photo courtesy of West Virginia Host Farms, wvhostfarms.org

Pitcock recalls that, when fracking first rose to prominence, many landowners did not understand the term conventional “because that was the only type of well.” By February 2014, there were as many as 3,696 unconventional wells, and shale production accounted for more than 80 percent of all natural gas produced in the state.

Approximately 40 percent of West Virginia’s Marcellus shale gas wells have been constructed on private property, and of those, nearly 70 percent are split estates, according to a 2013 study by Alan Collins of West Virginia University.

His research also found that those residents with split estates are more likely to report problems such as polluted water and land and surface damage. His report did not indicate whether this is because companies actually cause more damage on split estates, or because surface owners with nothing to gain from mineral development on their land are more concerned about potential impacts.

What is clear is that, because mineral rights are often owned by out-of-state individuals or, according to Pitcock, even the gas companies themselves, many surface owners are left in the dark about long-term plans for their property.

Even after the well is finished, workers may come up to several times a day for maintenance, and wells may be fracked up to 12 more times in subsequent years. News that wells might remain in production for the next 30 to 50 years can be numbing for landowners.

“I tend to feel like I’d like to think about it later, and then it won’t seem so bad,” says Crowder. “But then you come home and it’s absolutely as bad as your worst fears.”

Who Owns the Land?

When Crowder and Wentz moved to West Virginia in 1977, they already knew the mineral rights had been separated from their land decades ago. But like many who bought property before the Marcellus gas boom, they never imagined such an extensive operation could be placed on their property.

The two built a log cabin home and, in 1981, their son Nathaniel was born. Wentz learned to work as a woodturner and Crowder, who paints pastel portraits and landscapes, won awards for her work, and even has some pieces displayed in the state’s permanent collections.

The minimum required distance between gas wells and homes allows for construction at close quarters with neighboring residents. Courtesy of Terry Wild Stock Photography.

“We felt at the time that we were going to make our own life out of the mainstream, and raise a child in a rural environment,” Wentz says. “It was quiet and peaceful and we got to love it, but now it’s all torn up and we’re in the middle of an industrial zone. And at my age, you can’t really start over again.”

Before the well pad arrived, Crowder and Wentz divorced and agreed to split the property. The majority of the land taken by gas company EQT Corporation belongs to Wentz, but Crowder has also been affected by the impact of noise, traffic and air pollution, and the fear that their water has been contaminated.

Now, even on a calm day, a waft of natural gas is carried on the breeze to their homes and a 16-foot-wide gravel access road cuts through the woods. Lining both sides of the road are massive piles of trees where the company clear-cut a 45-foot right-of-way. In West Virginia, property owners are entitled to receive “reasonable damages” from the company, but Crowder and Wentz decided not to sign anything without a sense of what those damages would be.

“[The drilling companies] want you to sign ahead of time so they can tell you what they expect the damage will be and give you a dollar offer, take it or leave it,” explains Pitcock. “The problem with [trying to] negotiate is when they’ve taken out 20 more acres than they said they would, or completely bulldozed your orchard, or caused erosion problems and flooded out your vegetable garden, you obviously have more damages than what they predicted and already compensated you for, so it’s up to you as the landowners to sue them.”

Living with Fracking

For six months while the wells were being constructed, a noisy din hovered over Wentz and Crowder’s property around the clock. A towering drill rig operated nonstop to bore down more than 7,000 feet. Accompanying lights illuminated the surrounding area like a stadium, obscuring the night sky.

Today, drilling on the multi-acre well pad is complete, but nine separate wells and their accompanying condensate tanks remain. These special tanks heat the extracted gas in order to separate it from water and other liquids; although the process is comparatively quiet, the tanks require occasional releases of pressure. Carcinogenic vapors such as benzene, toulene and xylenes are emitted, and these heavy gases may accumulate in low-lying valleys rather than floating away.

All of this equipment, along with an average of 4 million gallons of water needed to frack each well, was hauled in by heavy diesel trucks and tractor trailers that precariously climbed up and down the mountainside access road built just above Wentz’s house. According to Pitcock, many of the truck drivers are workers from flat states such as Texas and Oklahoma, and they have gained notoriety for their inability to navigate the state’s winding, rural roads.

“There was a time we were averaging about 1-2 major accidents a week — that we knew of!” says Pitcock. “The first thing they’ll do when they run their tanker off into a ditch, is they’ll call the tow truck company that they deal with, and they’ll haul it away and it never gets reported.” Pitcock and local volunteers are watching, however, and they work to hold the industry accountable by photographing accidents and sharing information online.

A Watery Rebuke

Most landowners in Doddridge County have long relied on private wells for drinking water but, since drilling began several years ago, some residents have switched to using large plastic tanks called water buffaloes.

“They keep saying with people’s water wells that nobody can prove they’ve been contaminated by fracking, well all you have to do is drive around and anytime you see one of these water buffaloes, it means a person’s water well has been compromised,” says county resident Jonette Kirkwood, who has noted a rise in the number of houses with these 1,200-gallon white tanks in their yard. “The gas companies don’t just stick those in someone’s yard.”

West Virginia requires gas companies to provide an alternative water source in response to nearby contamination complaints, but this is not considered a legal admission of guilt. Legal condemnation would require a historical series of water quality tests, which companies are not obliged to provide. One local resident, who asked not to be named, notes that such tests can be prohibitively expensive for residents to obtain on their own. “You need baseline testing and you need to prove a change in your water; one test only captures water at that point in time.”

Wentz has had the property’s water tested twice so far, but he does not have baseline tests from before the company arrived. Pitcock remembers when Wentz had a one-acre frackwater pond near the well on his property — used to store the flowback of toxic wastewater that returns to the surface after a well is fracked — surrounded by a tall chain link fence.

“There was a sign here that said ‘Impaired Water. No Swimming,’” She laughs, then adds, “That stuff evaporates in the air with all those toxic chemicals. We have cases where they’d leave a pond like that for 2-3 years to evaporate what they didn’t pump out, and then if they pay the landowner an extra $20,000, he’ll let them just bury it there and cover it up.”

Unsettled Damages

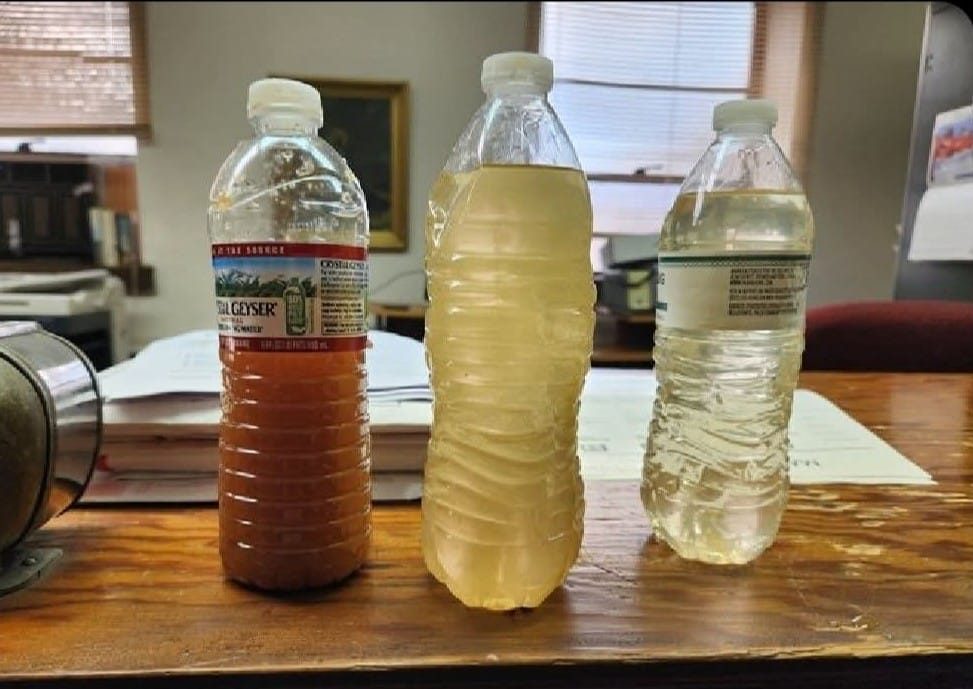

Some West Virginia residents living near gas drilling operations have received 1,200-gallon water tanks, like the one pictured above, from those companies after water quality test revealed contamination. Photo by Molly Moore.

Although EQT has essentially taken over a portion of Wentz’s land for the next 20 to 50 years, as far as auditors are concerned, those 37 acres still belong to him, and he is required to pay taxes on this land that he will likely never be able to make use of again.

EQT has finished drilling and fracking the well for now, but the daily rounds of truck traffic driving up to the well pad, the emissions from the drilling equipment, and the whistles from pressure valves at the well pad will not end.

“Drilling was very noisy and all, but it had a beginning and end. The traffic around David’s property will not end,” says Crowder. “Imagine if you did want to sell, especially to a younger family? You really feel like the place is ruined.”

Some West Virginians have responded by filing lawsuits for nuisance and negligence related to natural gas drilling, including environmental impacts, traffic and blocking public road access. Their complaints are directed at EQT and other natural gas companies including Antero Resources and Hall Drilling.

Even residents who owned their mineral rights and accepted payments to have a Marcellus well or pipeline built on their property have found that they agreed to more than they realized. “None of them ever had any idea that this was not the usual drilling,” says Pitcock. “They were in for something brand new, unconventional and far more devastating.”

“These people are saying ‘Why did I sign this? They told me they were only going to clear for a 16-inch pipeline and I came home and they took the whole side of my mountain and cleared all the trees,’” adds Pitcock. “Well, it’s too late when they’ve signed [the lease], you’ve got to read the small print.”

Feelings about what will happen to Doddridge County are mixed. For some, it’s time to leave; the Marcellus shale wells, and all the problems they have brought to the community, are here to stay. Others say it is important not to succumb to resignation.

“Who’s going to want to come here to live?” asks Kirkwood. “We only have I think 8,000 [residents] in the whole county and 800 in the town. And if people can’t sell their homes because their water’s no good, or because somebody’s put a great big well pad right in their land, what’s going to happen over the next 20, 30 years with the people here?”

Kirkwood’s adult children have suggested that she “Get out now while you can still get some value out of the house.” But the value of her home is less important to Kirkwood than the value of her community, where folks she knows stop by to chat or invite her to lunch as she tends her garden. “I’d rather just stay here where I belong,” she says.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

8 responses to “Digging Under the Surface: West Virginia’s Fracking Boom”

-

Antero paid me a whopping $6.89 royalty for a year’s worth of their kind-hearted drilling. I just feel so un-wealthy. THANKS, ANTERO!!!!!

-

DONT let them, are we not men? when they come we stop them, when they threaten us we break their legs.

-

Is it possible that my property is eroding due to my neighbors well? Honestly, in the last 2 years, I see more cracks in my ceilings and I feel like we are loosing ground…starting to slope. Neighbors fracked about 5 yrs ago.

Ohio

-

It’s so great to see some deep reporting on the oil and gas industry in WV and its impacts, within the context of communities and land ownership. My family owns a small acreage (surface and minerals) in Doddridge County.

-

I have the misfortune of inheriting a small plot of land with several dozen of my cousins. We do have the mineral rights, but from what I see in the articles I find on the ‘net we are treated like those who do not have mineral rights to their properties. When I refused to sign the contract i was told by an Antero representative that the company is going to take me to court because I am “infringing on the rights of others”. I looked at West Virginia Code Section 37-4-1 et seq. on the ‘net and was I ever surprised that a corporation can take away private property for the corporation’s benefit. {Also got a laugh at the section of the law which states the court can order the county to seize the land and “sell it on the courthouse steps”. Has West Virginia ever updated the laws of the state? Selling on the court house steps sounds like the 1860’s.) Why am I withholding? Antero is pushing a “fool’s contract” my way wanting me to sign. They will not place in the portion of the contract that is filed the ACTUAL amount of money they want to pay for the mineral rights. My cousins living outside of WV are all for the contract, “Where’s my money?” Antero has offered me twice the amount they were paid, but will not state so in the contract. Further, I know what it is like to live in the ares of Central Ohio that has oil wells in production. I wonder what all that petroleum that ais now in the air is doing to the health of those who live nearby. I am not signing their contracts.

-

and this doesnt even cover all the trash and bad attitudes from drivers and flaggers we have to deal w/.

-

I have a Marcellus less than 1500 feet on top of a hill behind my house. everything published above is absolutely correct. this is the second time weve had to endure this for the sake of the almighty dollar(though the first well was on property above up, they had to use our access to reach the site). I have only lived here 4 years, and I am 65 yrs. old. this is my dream house. what in Gods good name am I going to do if they ruin my well, or make us sick w/ all the pollution coming down over us? not only all that, but, I have nearly been run over more than once on a little one lane country, dirt and gravel road by HUGE trucks going a wee bit too fast for their weight and the road. please, good people of west Virginia, help us by voting for someone who will put a stop to fracking by outlawing it here. I live in Doddridge and we’re a hotbed of activity for gas production.

-

Honestly, can you believe this is happening in America? This speaks to the government takeover by corporations and in the case of Fracking, to the power of the worst, most profitable corporations of all, those in the fossil fuel industry. Where I live in Western North Carolina, the locals are such good, honest, hardworking Americans they have no idea how their elected officials have betrayed them. It is our job to counter the fossil fuel industry propaganda about how safe Fracking is. It’s only safe if it happens in the other guy’s backyard. Fracking is UnAmerican. It violates homeowner property rights as well as the safety and welfare of the American people.

Leave a Comment