Finding a Common Language

Lucy Hoffman, pictured at her desk in Linville, N.C., is one of the few people working to help Latinos integrate into communities in northwestern North Carolina.

Lucy Hoffman hears her cell phone buzzing at all hours. At Avery Amigos, a nonprofit dedicated to bridging the gap for the Latino community in northwest North Carolina, she assists Hispanic women and their families with a little bit of everything, including hospital bills, apartment leases, reliable transportation and English-learning classes.

The trouble is, she’s one of the only people doing this work, and it’s with a population that continues to grow.

From behind her cluttered desk, Hoffman waved a copy of a ticket. “280 dollars!” she exclaims. “That’s how much they fine you for not having a driver’s license!” That amount can make or break many Hispanic families’ budgets, she says.

According to a 2011 report from the Appalachian Regional Commission, Latinos account for 4.2 percent of the total Appalachian population, or over one million people. That’s up from one percent of the total population in 1990.

Their population doubled between 2000 and 2010, with more than 300 Appalachian counties experiencing an increase in Hispanic population that matched or exceeded the national average. Where Hoffman works, in Mitchell, Watauga and Avery counties, the Latino population has increased by 133 percent in the past decade, from 1,346 in 2000 to 3,141 in 2010.

Hoffman, who’s originally from Brazil, hopes that legislation will pass that will allow undocumented immigrants to test for driver’s licenses. That way, families can safely transport their kids to school, get to work and buy groceries. As things are now, those without licenses are afraid to drive anywhere, she says, and the road stops that police officers are known to set up near Latino neighborhoods certainly don’t help.

Defining Latinos in Appalachia

A 2007 study from Macalester College found that in 2000, foreign-born Hispanics comprised 49 percent of the Hispanic population in Appalachia, with the majority coming from Mexico, and lesser numbers coming from Europe, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. The remaining 51 percent, native-born, moved to Appalachia from another part of the United States, mostly the South.

Transplants from Latin America are settling in Appalachia in places with specific industries, says Dr. Barbara Ellen Smith, a professor of women’s and gender studies at Virginia Tech. Places such as eastern Tennessee with its poultry processing and western North Carolina with its Christmas tree farming are seeing booms in Latino population.

The immigration process for these workers isn’t a free-for-all, either. “You don’t get a visa to enter the United States to work unless you are highly skilled and you have an employer backing you,” Smith says. “[This] just doesn’t happen for ordinary folks.”

Due to a 25.3 percent poverty rate among Latinos nationwide in 2011, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, community doesn’t come easy for many Latinos, let alone in rural Appalachia. As one resident surveyed for a 2010 Appalachian State University report says, “Yes, we want to be together and help each other but it is hard to do that when we are all struggling.”

Faith-based groups and social services are often the first to lend a helping hand. But in places where there is a sufficient concentration of Latinos, such as Siler City, N.C., Smith says, those residents develop the communities themselves, creating Hispanic festivals and other forms of outreach and support.

In places such as Morristown, Tenn., there is local resistance to Latinos from groups such as the border-patrolling “Minutemen,” but there is also expanded food selection at grocery stores, multilingual signage in local businesses and unionized Latino poultry workers, whose successful struggles were catalogued in a 2007 documentary called “Morristown: in the Air and Sun.”

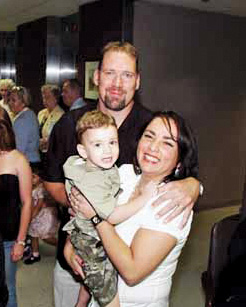

Derdlim and Rob Masten of Elkins, W.Va., with their child, shortly after Derdlim obtained U.S. citizenship in 2008.

Learning to Dance

A person eating at El Gran Sabor in Elkins, W.Va., should order the cachapas. It’s a traditional Venezuelan dish, pancake-like and made of corn, egg, butter and milk. “It’s our most popular dish,” says Derdlim Masten, who co-owns the restaurant with her husband Rob.

Derdlim is originally from Venezuela. She first met Rob in 2000 when she was visiting her cousin in Randolph County, where Elkins is located. Rob was a West Virginian, a music teacher for a local school and a saxophone player for a Latin band.

Six months after they first met, Rob asked Derdlim to teach him how to dance. They hit it off, she speaking little English, he speaking little Spanish. Instead, says Masten, “we communicated by dancing.”

They married in 2002 and started their restaurant soon after.

At first, things were a little tough at El Gran Sabor, whose name translates to “The Great Flavor.” Because many potential patrons had the heavily-Americanized Mexican palate, Masten had to offer burritos and tacos. “It was hard for me to convince them that I’m not Mexican,” she says.

Now, El Gran Sabor can offer a full Venezuelan cuisine and vegetarian options with no downturn in business. Masten says there are not many Latinos in town — the last census counted 75 residents out of 7,094 — but now “more people know about the Latin people” in Elkins.

Masten responded emphatically when asked whether her husband now knows how to dance. “Oh, yeah!” she says. “He’s a professional.”

The hills and hollows of this region have always been more diverse than people think, and Hispanics are only the latest group in Appalachia to ask for the possibilities of social and economic mobility. As Dr. Barbara Ellen Smith says, “It’s not just an immigrant question — it’s a class question.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment