Front Porch Blog

When it comes to revealing external costs, the true cost of coal on the environment and our health must come first.

At the Democratic National Convention, Appalachian Voices’ staff attended and participated in several panel discussions and events relevant to our work. Perhaps the most engaging forum that I was fortunate enough to attend was the “Summit for a Sustainable Economy,” hosted by the American Sustainable Business Council.

Shortly after I arrived, flipped through the materials and familiarized myself with the panelists, I began to hear things from the front of the room that piqued my curiosity, things like “Not everything with a price has value, not everything with value has a price.” It didn’t take long to realize that these were folks who understand not only the moral reasons why people must come before profit, but that it’s also just good business.

Lew Daly, director of the Sustainable Progress Initiative and a senior fellow at Demos, did not speak this priceless phrase as a spontaneous thought, but as if it were a chief operating principle that should be accepted by businesses of all sizes, publicly and privately owned.

During the transition from a manufacturing-based to service-based economy, analysts began calling it a shift to the new economy. But that period of high growth soon stalled, and eventually the bubble burst. We’ve become disillusioned with the new economy and now thousands of businesses and groups like the ASBC are revealing the true economy. They know that calculating the true cost of coal — carbon pollution, environmental degradation and its many other external costs — imposed on the local and global environment will be essential in achieving this goal.

The ASBC is calling for a paradigm shift by questioning the economic models we’ve become so dependent on and encouraging businesses and policymakers to pursue sustainable practices that benefit people, the planet, and generate profit. The concept, which the group calls the “triple bottom line,” is an approach that rejects the false choice between short-term profit and long-term benefit.

Lew Daly’s comments led to a discussion of the need to develop “Beyond GDP” metrics and to use them to inform policy decisions in federal and state-level governance. The problem with the logic behind our gross domestic product — and it’s cousin the gross national product — is that it assumes that everything with a price has positive value, as long as it contributes to growth. A recent piece in Orion magazine that critiques our reliance on GDP to make decisions titled “The Mismeasure of All Things” opens with an anecdote exposing that distortion:

ON A ROAD NOT FAR FROM MORGANTOWN, West Virginia, my guide pulled over to show me the peculiar color of a certain river. It was orange. The rocks and creek bed were a hue somewhat brighter than rust but duskier than the reflective vests worn by utility crews. Years of drainage from coal mining tailings, high in the acid produced during the washing of the coal, had killed everything in the watercourse, rendering the water a moving hazard and contributing to the economic decline of the area. Coal had also sickened the bodies of miners, as well as the atmosphere.

Yet the years when rivers like the one I saw became industrial sewers were some of the most prosperous in the history of the state of West Virginia, when men and women were relatively well employed, cashing their paychecks to pay for groceries and rent, televisions and cars, medicine and property taxes. Every conventional accounting of the economic significance of the coal industry includes the wages paid, the small businesses sustained, and the quarterly profits of corporations, but not the rotted lungs, or the polluted waters, or the rising oceans that inundate low-lying slums in Bangladesh. These other effects, equally direct, receive no valuation when coal’s contribution to economic growth is tallied. They are invisible to the gross product of West Virginia or the United States. [emphasis mine]

Burning coal for electricity remains the classic example of the debilitating toll externalities can take. At the summit, Mr. Daly repeatedly invoked coal to make his case. “Pull out just the health costs driven by coal; those costs are twice as large as the value added of that industry,” he said. “The idea that coal is an economic winner is a complete myth.”

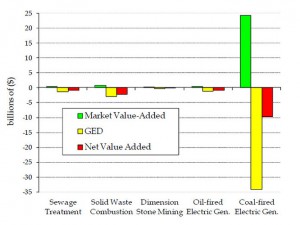

Coal-fired electricity seems like a great investment, before considering the resulting gross external damages. Chart from Environmental Accounting for Pollution.

Daly cited a 2011 report by William Nordhaus, a Yale economist who has written on the economics of climate change. “Environmental Accounting for Pollution in the United States Economy” presents a framework to account for carbon pollution and environmental degradation of coal-fired electricity and measure it against the value added by that industry. According to Nordhaus, “the largest industrial contributor to external costs is coal-fired electric generation, whose damages range from 0.8 to 5.6 times value added.”

In the search for solutions, economists like Nordhaus, psychologists and others have created new measurements: the Genuine Progress Indicator, Leisure-Adjusted GDP, the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare, and environmentally-adjusted or Green GDP, to name a few.

In 2004, Niu Wenyuan, a senior economist and adviser to the premier suggested that China adopt an environmentally adjusted GDP. Wenyuan believed that, using Green GDP metrics to quantify the costs of air and water pollution, he could begin to temper his nation’s obsession with growth. Unfortunately, when the calculations for 2004 were published in September of 2006 claiming a loss of 511 billion yuan, about $66 billion, political leaders were quickly turned off by the prospect of doing anything with the information.

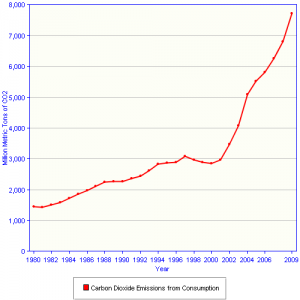

It was also in 2006 that, for the first time, China surpassed the United States as the largest contributor of carbon pollution. And earlier this year, China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection estimated environmental costs in 2009 at 1.4 trillion yuan or $222 billion.

Cheap Ain’t Cheap

Last fall in Wise County, Va., southwest Virginia resident Ben Hooper repeatedly told a group learning about mountaintop removal that “cheap ain’t cheap.” And he’s right. If the true cost of coal isn’t reflected by our electricity bill, it is by the number of premature deaths, heart and asthma attacks, birth defects attributed to coal pollution. You may be able to put a price on that, but I challenge anyone to determine the value lost.

It’s the unacknowledged externalities of burning fossil fuels that perpetuate the idea that Congress should end subsidies for renewables and let the production tax credit for wind energy expire at the end of this year. It’s externalities that promote investment in coal-fired electricity as the societal toll is ignored. They lead to the creation of terms like “overburden” and “spoil.” And they make dumping the remains of a desecrated mountain into a valley a streamlined way to increase profits.

Cheap ain’t cheap. And if the true cost of mining and burning coal were reflected in its price, few would be able to afford it or want to buy it at all.

In 2005, China's carbon dioxide emissions were two percent below those in the United States. The next year, China’s emissions surpassed those of the USA by eight percent

But there are positive externalities too. And identifying and assigning a price to them is just as important in creating the transition to a just, sustainable economy. Investment in education, by the logic of the GDP, for example, is spending. In the true economy, it’s an investment in the most valuable resource that exists in a knowledge-based economy: human capital. By the logic of the GDP, environmental regulations that protect human and environmental health are anti-growth. In the true economy, they create jobs, preserve health and natural capital — the trees, and pollinators, and pristine streams that perform services unasked, the way they always have and would like to continue to, even though they don’t ask.

“As a policy driver, pricing those positive externalities is going to be key to recognizing the value of those investments,” Daly said at the summit. Surely doing so will make an even stronger case for pulling back the curtain hiding the price that coal pushes off on all of us.

Some 60 days from an election centered on what’s good for the economy — and not necessarily for people, or real progress — in a city bustling with the excitement of the Democratic party’s national convention, hearing these ideas was refreshing. From the 47th floor of Charlotte’s Hearst Tower, I was able to look down and watch the giant machine roar, but in a small nook between the gears of progress are the neglected bolts and screws that must be incorporated for the machine to work for all of us.

In 2009, Harvard Business Review reported that “Sustainability is now the driver of innovation” and as Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has remarked, “GDP tells you nothing about sustainability.” All those advocating for sustainable business practices and using metrics that reveal the true economy aren’t imagining a new frontier, they’re revealing the one we inhabit.

While it will be difficult to assign a price — but much more so a value — to both negative and positive externalities, doing so is essential. New ways to measure progress will go a long way in saving lives, moving toward sustainability and economic stability. If this sounds like pie in the sky talk, it may be because more than a true economy — as the ASBC, Niu Wenyuan, William Nordhaus, Joseph Stiglitz and others realize — we need true economics.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *