Front Porch Blog

Special to the Front Porch: Our guest today is Lisa Sorg, environmental reporter for N.C. Policy Watch. A seasoned journalist, Lisa was the editor and an investigative reporter for INDY Week, covering the environment, housing and city government. This post originally appeared on the N.C. Policy Watch blog The Progressive Pulse.

Lisa Sorg

While North Carolina is rightfully focused on the coal ash scandal, another environmental tug-of-war is strengthening in some of the state’s poorest areas.

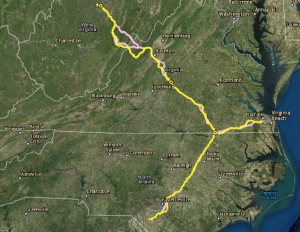

Co-owned by Duke Energy, Dominion, PSNC and AGL Resources, The Atlantic Coast Pipeline would ship natural gas 550 miles, from the fracking hotspot of West Virginia through sensitive, federally owned land in Virginia, and then into eastern North Carolina.

Once it enters in Northampton County, near Pleasant Hill, the pipeline would span nearly 170 miles through eastern North Carolina. The pipeline — 3 feet in diameter, about as big around as a baby pool — would roughly parallel I-95, passing through historic plantation land and Native American communities. It would end just north of Pembroke, in Robeson County.

Backing the a $5 billion project is EnergySure, a coalition of more than 200 special interest groups from several states vying for a piece of the financial pie: chambers of commerce, utilities, construction and “right of way” companies, which pressure adjacent landowners to sell, voluntarily or through eminent domain. In North Carolina, supporters include the Energy Policy Council, appointed by Gov. McCrory and lawmakers, the NC Chamber of Commerce and the Pork Council.

The Pork Council could benefit because of recent state legislation, the NC Farm Act, which prioritizes using swine waste to fuel natural gas plants over renewable energy.

The group’s slogan: “Don’t let opponents hinder new jobs.”

The ACP would increase fracking impacts in W.Va. and harm communities along the 600-mile route through Va. and into N.C.

The promise of jobs is seductive in eastern North Carolina, where a quarter to a third of people live in poverty. And this is precisely why these types of projects are placed in low-income communities: to reduce the chance of resistance.

Yet, as the opposition points out, the construction jobs are temporary. Clean Water for North Carolina projects that only 18 permanent jobs in North Carolina would be created by the pipeline, none of them guaranteed to go to local residents.

At a recent citizens’ meeting in Fayetteville, Ericka Faircloth of Eco Robeson explained how the loss of property, either outright or in its value, is particularly significant in Native American communities. (However, some members of the Halowi-Saponi tribe belong to EnergySure.)

“It has greater implications,” Faircloth said. “Our identity is linked to our sacred lands. We want to protect land for future generations of indigenous people.”

Natural gas, while touted as a cleaner alternative to coal is not necessarily “clean.” It is a fossil fuel. Over-reliance on natural gas for electricity, reports the Union of Concerned Scientists, carries its own risks to the climate. Fracking, a common form of gas extraction in West Virginia can release methane, a major component of greenhouse gases.

The gas that would run through the pipeline would not necessarily serve North Carolina. Natural gas is a commodity, like oil and corn, and is sold on the open market. And as Nature pointed out in late 2014, energy forecasters could be reading the tea leaves incorrectly, projecting an overly optimistic estimate about the amount of natural gas that is accessible.

Rivers, streams, swamps, wetlands and other environmentally sensitive areas would also be disrupted, some of them permanently, by the pipeline. The routing would place it over several key waterways, including the Little River in Johnston County; Swift Creek in Halifax, which feeds the Tar River; the Neuse River and the Cape Fear.

Other communities in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania have successfully defeated gas pipeline projects. “It’s up to us to say we don’t need it,” said the Rev. Mac Legerton at the Fayetteville meeting. “We can win this.”

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, known for its leniency toward these projects, must approve the pipeline before it can be built.

PREVIOUS

NEXT

Related News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Where does it come through in Robeson and Scotland Counties, NC? Map please.