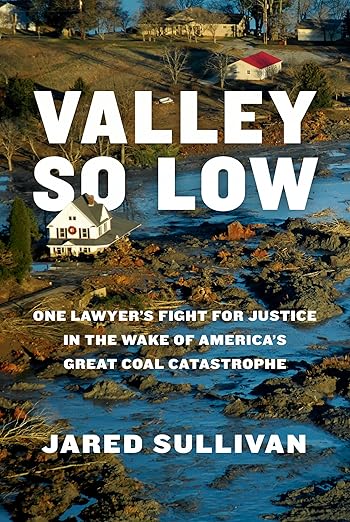

In “Valley so Low,” an environmental disaster creates a crisis for cleanup workers – and restitution proves elusive

By Ashlea Ramey

After more than a decade of litigation, a tentative $77.5 million settlement for workers affected by one of the United States’ largest environmental disasters should have felt like a victory.

But as “Valley So Low,” the debut book from journalist Jared Sullivan, explores, a drawn-out legal process and a lack of accountability by those responsible for the incident and its repercussions makes the legal victory hollow – especially as the plaintiffs have paid, and continue to pay, an untenably high price.

Fueled by righteous anger and girded with more than a dozen perspectives from workers, their families, attorneys and experts, “Valley So Low” explores nearly 15 years of damage, ramifications and hard-earned, albeit still meager, justice, after a Tennessee Valley Authority power plant coal-ash dike collapsed on Dec. 22, 2008. Through Sullivan’s reporting and numerous firsthand accounts, “Valley So Low” shows that, much like the dike itself, while the initial destruction was significant, the real harm lies underneath. And when it breaks loose, it is catastrophic.

The spill covered 300 acres and destroyed or damaged 26 homes, and “Valley So Low” gives a heart-racing account of those early rescue hours. It also begins seeding the book’s underlying David-and-Goliath motif of everyday heroes and underdogs, with early pages recounting Kingston residents scrambling for safety and to rescue their neighbors before their homes collapse. They’re successful: Despite the area being coated in enough sludge to fill the Empire State Building nearly four times, everyone survives the initial spill – though a body count will come.

The initial plaintiffs against TVA have homes and properties that were damaged or destroyed in the spill, and Sullivan begins to introduce the attorneys who will take on the case and face off against some of the most formidable foes of their careers. It also positions the intricacies that will stymie the later cases, laying out TVA’s historic legal immunity and introducing the web of TVA and its contracted engineering groups that will be involved in later cleanup efforts. For the property damage, though, resolution and recompense are possible, even if not what the spill’s first victims would have expected.

Closure is more elusive – and frankly, impossible – for the later cases. The coal-ash spill necessitated a massive cleanup effort, for which TVA hired Jacobs Engineering, a construction and environmental cleanup firm. While TVA and the federal Environmental Protection Agency held broad responsibility for the cleanup, Jacobs is tasked with day-to-day project management and worker safety. When that safety proves at best insufficient and at worst gallingly negligent, Jacobs is the party the workers and their attorneys try to hold responsible.

The effects of the coal-ash cleanup efforts become apparent as workers began reporting dizziness, nosebleeds and shortness of breath. “Valley So Low” threads their stories from the very beginning, with one of the plaintiffs, Ansol Clark, responding to an early call about the disaster, where he begins working alongside the people who will later join him in the lawsuits.

“Valley So Low” features Ansol and his wife, Janie, heavily as Ansol’s health fails, the cases proceed, and Sullivan explores the systemic blockades and failures that contributed to the workers’ illnesses and the spill itself. Along the way, Sullivan tells other workers’ stories, including a father with young children who also become ill, a part-time Baptist preacher whose lungs deteriorate until he can barely testify at trial without coughing, and another worker who is told by a Jacobs safety supervisor that he’d be “run off the site” for wearing a dust mask.

Each story – the Clarks’ is told most in-depth – showcases the workers’ diverse backgrounds and beliefs. But they share a similar undercurrent: These are, for the most part, men who worked, and worked hard, to provide for themselves and their families. They never expected that work could erode their vitality and virility, and with it, their families’ futures, like cleaning up the Kingston coal ash spill did.

As the workers tackle both the cleanup and their health struggles, the attorney who takes their case, Jim Scott, is also given a central point of view. As Scott doggedly pursues justice, own life follows a fractured path, with a fraught divorce, challenges of single parenthood and his own health struggles coloring his progress.

Where “Valley So Low” truly shines is telling these stories – the vivid lives and, too often, devastating ends of the Davids facing off against the Goliath of TVA and Jacobs. The companies, too, are positioned as characters of their own, with Jacobs and some of its leaders solidly fitting the villain profile, though TVA’s own history – solidly recapped by Sullivan – is a bit more fraught, as its nearly 100-year story transitions from being “emblematic of good, benevolent government” to the “consummate environmental bully” throughout the Southeast.

That juxtaposition, while not heavily featured, is present throughout “Valley So Low.” Prior to the creation of TVA, the rural areas it serves were appallingly impoverished. It became an economic powerhouse – with multiple meanings for that – for those communities, and in fact, when Ansol is first contacted for the project, he and Janie are cautiously optimistic about what the large paychecks can mean for their retirement. They don’t yet know this potential opportunity of a lifetime will cost Ansol his life.

Compared to the gut punch of the plaintiffs’ stories, “Valley So Low” drags a bit in its legalese and detailing of the court processes. Tracking the cases through layers of litigation and appeals will likely only appeal to courtroom drama aficionados, and the intricacies of legal immunity, the United States judicial system and Scott and his colleagues’ reams of discovery and briefings aren’t as engrossing as the initial spill rescues. However, the arguments buttressing TVA and Jacobs’ handling of the accident and their abdication of responsibility lay out the all-too-familiar injustice felt by workers and rural communities, and it fuels anger and horror at Jacobs’ pursuit of its multimillion-dollar payday, at the cost of workers’ lives.

With that, even the final settlement offer fails to find true justice. That sum, after being split among plaintiffs and accounting for attorneys’ fees and other expenses, also includes a requirement to repay insurance companies for workers’ earlier medical expenses – so the most heavily affected could potentially receive the least cash.

And, as “Valley So Low” points out, no dollar amount could fully restore health or bring back those who succumbed to their illnesses. Even before Ansol’s health takes its final tragic turn, his condition deteriorates enough that he and Janie know he will never be the same – that even before losing him for good, he will never come back completely.

Thanks to “Valley So Low,” their stories can be heard – and can also serve as a warning. Sullivan notes that, during the first Trump administration, the EPA loosened regulations that were created to protect communities from coal plant wastewater and coal ash, and federal trends now signal that these safeguards could once again be at risk. To that end, how many more Davids – in the form of Ansol Clarks and Jim Scotts – are out there, and how strong and impermeable will their Goliaths become? What price will they pay?

“Valley So Low” was published in October by Penguin Random House and is available in hardcover, ebook and audio formats.

Learn more about the Kingston coal ash cleanup workers at RememberKingston.org.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

One response to “In “Valley so Low,” an environmental disaster creates a crisis for cleanup workers – and restitution proves elusive”

-

Thanks for the review. My copy of the book arrived this week, looking forward to reading it

Leave a Comment