Snorkeler Casper Cox Explores Appalachia’s Diverse Freshwater Life

Two male Alabama shiners spar over a spawning site in the Conasauga River. Photo by David Herasimtschuk.

“One of the pleasures of exploring and snorkeling in the Southeast is crossing into different watersheds and encountering new species … Land-locked Tennessee has more freshwater fish species than any other state of our union,” writes avid snorkeler Casper Cox in “Snorkeling the Hidden Rivers of Southern Appalachia.”

Biodiversity maps based on data published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences support Cox’s statements about fish diversity. The map for fish distribution in the United States shows the Southeast as having the greatest diversity and number of species unique to the region.

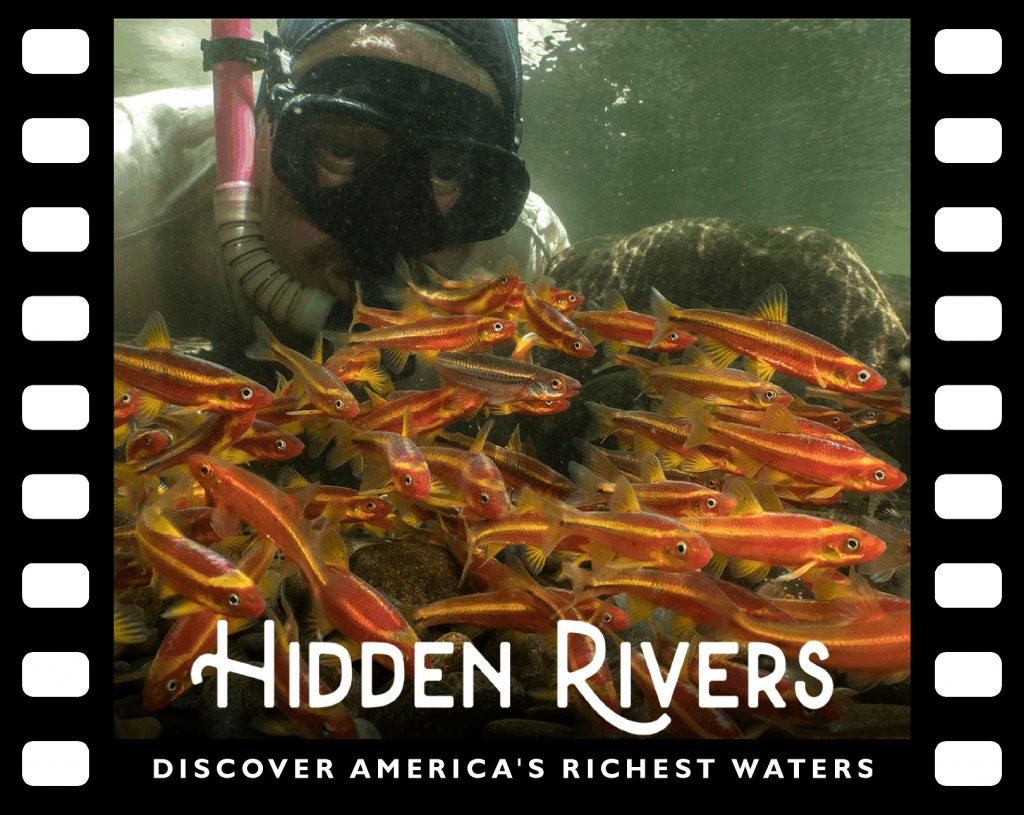

For two decades, Cox has been snorkeling the rivers and streams of Appalachia. He appeared in the 2019 film Hidden Rivers, produced by the Oregon-based nonprofit organization Freshwaters Illustrated. He then wrote, designed and produced the companion book “Snorkeling the Hidden Rivers of Southern Appalachia.”

“In crystal clear water on a sunny day, everything appears to be enlarged,” Cox says. “The snorkeler’s facemask enlarges the fish. The plants sway in the current and the sun plays on the rippled surface of graveled substrate.”

He has shared that beauty with others by leading snorkeling trips in cooperation with the Cherokee National Forest at several Tennessee creeks and rivers, primarily the Conasauga River. Although the Conasauga is popular among bass fishers, it also has fish unique to its waters because of its geographic isolation from the Tennessee River watershed. It is Tennessee’s only river that is part of the Mobile Bay watershed.

“There are fish found in the Conasauga River which are found nowhere else in the world ” Cox says. One of these endemic species is the Conasauga logperch. Another is the bridled darter.

On the inside cover of “Snorkeling Hidden Rivers Southern Appalachia,” writer and snorkel expert Casper Cox peers over a redtail chub mound active with Tennessee and striped shiners. Photo by Gary Hansell.

“The Conasauga logperch had been undocumented and missing for several years,” Cox explains. “In 2010, I found an established population of them and alerted Conservation Fisheries, Inc. in Knoxville. They captured several males and females and reared several hundred, tagging them with fluorescent tattoos and releasing them at various locations in the Conasauga River.

“I also see rare and endangered species such as blue shiners, holiday, and amber darters,” he continues. “The Conasauga is a wonderful river to explore as its waters are often clear and silt-free, being protected by the forested watershed of the Cherokee National Forest.”

Other rivers in Tennessee that Cox has investigated include the Big South Fork of the Cumberland River, which begins on the Cumberland Plateau and is a tributary of the Ohio River, draining into the Mississippi. He has also explored tributaries of the Tennessee River that are in the Mississippi River drainage, which include the Hiwassee River, the Little River, and the Tellico River and its tributary Citico Creek. Snorkelers in these rivers might see fish ranging in size from the tiny tangerine darter or yellowfin madtom to the large and voracious longnose gar.

The Mystery of the River Chub

Cox’s snorkeling experience is not limited to Tennessee. He assisted Ed Scott with an inventory of freshwater fish in Linville Gorge. Scott, a freshwater biologist retired from Tennessee Valley Authority, conducted an inventory of fish in streams of the Blue Ridge Parkway for the National Park Service, which he describes in the 2014 article “Blue Ridge Parkway Fish Survey, 2007,” published in American Currents.

Scott identified, counted and released fish in the waterways flowing from the Blue Ridge Parkway to the Atlantic drainage, including tributaries of the Catawba River, the Yadkin River, the Roanoke River and the James River. He also counted fish in the Blue Ridge tributaries of the Mississippi River drainage via the New River and the Tennessee River.

As expected, Scott found bluehead chubs in the Atlantic drainage and river chubs in the Tennessee and Mississippi River drainages. The Blue Ridge Mountains are a biogeographical barrier in the distribution of these fish.

But then, while conducting his freelance research, Scott found a river chub in the upper reaches of North Carolina’s Linville River. Since the Linville River is part of the Atlantic drainage, he had expected to find bluehead chubs there.

The river chub from Linville River was an anomaly, so to learn more about this strange finding, Scott and Cox snorkeled the area above Linville Falls. They found only river chubs.

Geologists believe that the upper reaches of the Linville River once flowed west into the Tennessee River drainage, but the stream was captured by the east-flowing Linville River possibly as part of a geologic upheaval or other shift more than 10,000 years ago. This would explain the presence of river chubs in the Linville River.

Chubs: A Keystone Species

A few years ago, Cox guided a BBC film crew that came to the Tennessee River drainage to document the river chub for the “Seven Worlds, One Planet” series, which aired in 2019. The river chub is just one of many Southeastern species of Nocomis, or mound-building chubs. Though only about 12 inches long, chubs are important to many other fish.

“The various species of chubs gather stones into a mound about 1 foot high and 3 feet in diameter,” Cox says. “These mounds are situated in flowing, silt-free water, often at the heads of riffles or just downstream. The mounds offer protection for the developing eggs as they are covered by stones to prevent predation, yet the spaces between the stones provide flowing oxygenated water to aid in their development.

“Not only do the chubs use their mounds to spawn, but many other species take advantage of the chubs’ work. Stonerollers, as well as striped, warpaint, Tennessee, saffron, and scarlet shiners can all be seen swarming over these active mounds in the springtime. It becomes quite a show to witness as the colors are vibrant, nearly electric, with various species in enhanced spawning colors,” he says.

Start Snorkeling

According to Cox, opportunities for this hobby are limited only by the number of clear rivers. Beginners can refer to his book for guidelines, but a few basics include being aware of safety concerns, planning the trip and letting someone know where you are and when you will return. Beginners would also be well-advised to participate in guided trips for their first few adventures with snorkeling.

Cox canceled his guided trips to the Conasauga for the 2020 season due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but he says he is optimistic about resuming them in 2021. Guided trips on other rivers are available from various guide services, but probably not in 2020.

Experienced snorkelers who understand the safety issues involved can engage in do-it-yourself snorkeling. Adventurers might see a hellbender in the Hiwassee River, a brook trout in the Tellico, or view a fish they have never seen before just below the surface of a local river.

Just beware of sudden water releases from dams or heavy rains that can wash a snorkeler downstream with disastrous results. Additional hazards include fallen trees, rapid currents, thunderstorms and other river dangers.

A commitment to water quality

Cox’s dedication to water quality has led him to regularly participate in the annual Tennessee River Rescue event, where participating residents throughout the Chattanooga region collect trash from the banks of the river and its tributaries.

Cox initially assisted with the North Chickamauga Creek zone. He began by collecting fish and other aquatic life and creating a temporary display in an aquarium for volunteers to see the creatures that would benefit from their cleanup efforts.

In 2018, he led a team of snorkelers to collect trash from the North Chickamauga Creek, which he described in an article for American Currents magazine.

The Tennessee River Rescue team would have celebrated their 32nd anniversary this year, but the event is canceled due to COVID-19. Organizers are encouraging individuals to collect trash while on their own outings and to speak out on social media about eliminating single-use plastic

During the hot summer months of 2020, Cox has conducted his own stream cleanup. He kept cool in the North Chickamauga Creek while snorkeling and gathering 13 large bags of trash.

The rivers of the southern Appalachian states are many and varied. They beckon novice and experienced snorkelers alike. Fish-watchers may also see crawfish, salamanders, freshwater mussels and other aquatic life. Excitement awaits, but please snorkel safely and be respectful of the habitat these creatures depend on.

This banded darter was photographed by Casper Cox, who corralled it with a friend. Cox provides snorkeling photography tips in his book, “Snorkeling Hidden Rivers Southern Appalachia.”

Snorkeling the Hidden Rivers of Southern Appalachia

Casper Cox wrote “Snorkeling the Hidden Rivers of Southern Appalachia” as a companion piece to the film Hidden Rivers, produced by Freshwater Illustrated. He included stunning photographs of aquatic life, both his own and others by the Hidden Rivers photographers.

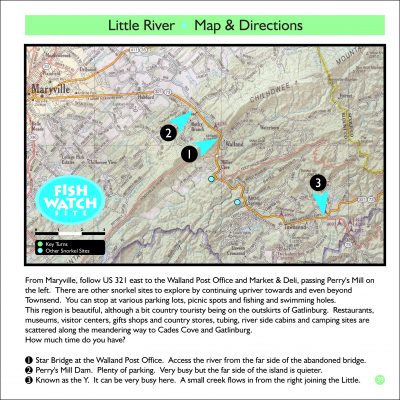

Contents include a guide to the following seven snorkeling opportunities, each section complete with photographs, maps and points of interest: Conasauga River, Hiwassee River, Tellico River, Citico Creek, Little River, Big South Fork of the Cumberland River and Big Swan Creek.

The book includes other pertinent information, with sections titled Aquatic Diversity, Researching and Locating other Snorkel Sites (with 13 specific sites named), Snorkel Gear and Equipment, Safety Concerns, Environmental Issues, Species Diversity, Rare Species and Aquarium Care and Mussels. The book also describes several leading aquatic conservation organizations in East Tennessee, including Conservation Fisheries Inc., and the Tennessee Aquarium and its conservation institute.

To order a copy, visit FreshwatersIllustrated.org or NANFA.org.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *