Making Music, One Instrument at a Time

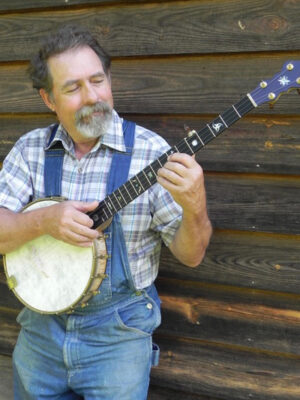

Mac Traynham plays banjo #118 outside his shop. Made of local and exotic woods and featuring handcut inlays, this instrument is available for purchase. Photo by Hanna Traynham

By Hannah McAlister

In Appalachia, stringed instruments are closely tied to the traditional bluegrass music the region is known for. The word “luthier” refers to someone who builds or repairs stringed instruments, and comes from the French word “luth.” Luthiery has deep roots in the southern mountains. According to the Appalachian School of Luthiery, the first dulcimers made by James Edward “Uncle Ed” Thomas appeared in Hindman, Ky., in 1871. Since then, the craft has been a staple in the region.

Mac Traynham

Mac Traynham first became interested in handmade instruments in the mid-70s when he commissioned a banjo and guitar.

That guitar was renowned luthier Wayne Henderson’s number 31; Henderson has now made more than 700. To this day, Traynham cherishes the instrument.

Traynham began visiting the shops of luthiers such as Henderson, the late fiddle-maker Albert Hash and the late banjo-maker Kyle Creed. In 1978, with the help of a Vermont luthier, he made his first banjo with a neck of birdseye maple that he obtained from an old door.

After that, Traynham had his first order, which he made at the luthier’s shop in Vermont. He moved to Grayson County, Va., and in 1984 opened an official shop, which has been located in Willis, Va., since 2000.

At first, he worked as a cabinet-maker, with banjo-making as a side business. Banjos went on the back-burner due to family life, but became more of a priority after his children finished high school in the mid-2000s.

Traynham says he typically works on two or three banjos at once, using a combination of wood machines and hand tools. Most of the neck shaping, inlay work, and final sanding and shaping he completes by hand.

“I get excited about it when I see a board that’s got some pretty figure in it,” says Traynham, stating that he still thinks birdseye maple is the prettiest wood.

“Maple, cherry, walnut, dogwood and sycamore have aspects about them that are different from each other but they’re all good for one reason or the other,” says Traynham, explaining that it can take some experimentation to find what sounds best.

For the fingerboard material, Traynham tends to use more exotic woods like rosewood or ebony, although he’s conscious of the negative environmental impact of using rare rainforest wood. He seeks out repurposed rosewood that was cut down decades ago. Wary of contributing to the destruction of the rainforest, occasionally he uses a recycled paper product that works like wood, known in the luthier community as Richlite.

In 2010, Traynham’s apprentice, Robert Browder, wrote a book titled “BanjoCraft.”

“Since then, a lot of people have said that they’ve read that book and it helped them get where they want to start trying it themselves,” says Trayham. “So I have a hand in inspiring some of the young people.”

Jayne Henderson

Jayne Henderson made her first guitar to help manage student loan debt after obtaining a degree in Environmental Law and Policy from Vermont Law School. Her father, acclaimed luthier Wayne Henderson, agreed to help her if she would come to his shop and do the work herself.

“I thought it’d be terrible but it was so much more fun than I ever expected,” says Henderson. “I got to hang out with my dad and understand why he loves being out in the shop so much. It was one of the best things that I’ve ever gotten to do.”

Jayne Henderson plays one of her hand-built guitars. Photo by Kate Thompson/Betty Clicker Photography

After selling her first instrument, Henderson made another while completing an AmeriCorps service term with an environmental organization in Asheville, N.C. Then, Henderson convinced her organization to give her time off to build a third guitar, under the condition that she donate the proceeds to their Riverkeeper program. This was the first with her name on the headstock and was made from local materials.

Henderson was hooked. In 2011, she opened EJ Henderson Guitars and Ukuleles and began pursuing instrument-building full time.

Henderson strives to make guitars in an environmentally conscious way. She prefers to use local, thoughtfully harvested woods with similar characteristics to more popular, exotic woods, such as Brazilian rosewood and mahogany, which have been over-harvested.

“In that way, I can at least get people thinking that we need to conserve our resources,” says Henderson. “I don’t push it hard but that’s what I do. I make smaller-body instruments that use more scrap wood. My favorite woods to use are oak, ash, maple and walnut, and they sound just as good as mahogany or rosewood, if I manipulate the materials.”

These days, Henderson has a multi-year waiting list.

When she’s building for a client, Henderson is all about building a relationship with them.

“I love to get to know [the client], their background and a little bit about them so I can get a taste of their personality,” says Henderson, “Then, I go through and I check wood. I decide what is going to go best for them, their personality, whatever their playing style is.”

Henderson adds herself into her pieces by doing creative inlay design by hand.

“It’s really important for me to see people open the case to see the thing that I made for them, and see that reflected in their eyes and to hear them play it, and see the joy that it brings,” says Henderson.

John Hollandsworth

John Hollandsworth began playing the autoharp at the age of 6 with family in Southwest Virginia. As he grew older, he found it difficult to find someone to work on his instrument, so he decided to teach himself. When other players learned of his skills, they began to bring their instruments to him for repairs and modifications.

Hollandsworth’s lifelong interest in woodworking, as well as his dissatisfaction with factory-made autoharps, led him to build his first autoharp for himself in 1989.“I kept seeing problems — the same type of problems, bad glue joints or other construction problems — that caused failures,” says Hollandsworth. “It was one of those things where I knew, from looking at it, things not to do.”

Shortly after, Hollandsworth was invited to play at the Mountain Laurel Autoharp Gathering, founded by master luthier George Orthey of Pennsylvania.

“I showed him the instrument that I made for myself and he thought it was pretty good,” recalls Hollandsworth. “He said, ‘You should really start making instruments.’”

Initially, Hollandsworth declined. But when his children were older, he decided to give luthiery a shot and Orthey took him on as an apprentice.

Hollandsworth recalls Orthey did not give him any patterns or information before he designed his first instrument. “I thought that was a really good idea because I don’t think anybody that builds things wants to copy something that somebody else is already doing,” he says.

In the early ‘90s, Hollandsworth opened his own shop, Blue Ridge Autoharps, in Christiansburg, Va. Each autoharp he builds reflects the buyer’s preference of woods, set-up and chord arrangement. His autoharps can now be found throughout the United States and in 10 different countries.

Making instruments was not his main profession, but now that he is retired, he dedicates more time to his shop and his waiting list of orders, completing one or two autoharps a month.

Even though he is a master luthier, Hollandsworth says he is still learning from others in the autoharp community.

“I think most people that build musical instruments really try to build an instrument that they enjoy the tone of,” says Hollandsworth. “You are always looking for the magic combination of wood and crafts to fine-tune the sound that you’re looking for. That’s the life-long goal. Nobody ever really achieves that perfectly, but the more instruments that you make the more that you learn about it.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a Comment