The Appalachian Voice | April 11, 2018 | No Comments

By Brian Sewell and Molly Moore

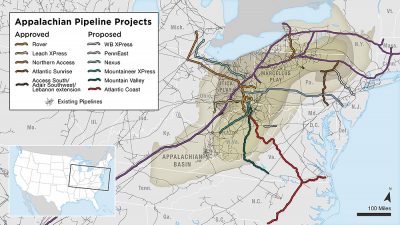

Click to enlarge. Map produced by The Center for Public Integrity and NPR (Leanne Abraham, Alyson Hurt, Katie Park) and modified by The Appalachian Voice to add the Mariner East 2 and Tennessee Gas Pipeline.

With permits issued and construction activities underway, controversy continues to follow major natural gas pipeline projects in Appalachia. Lawsuits, protests and public scrutiny targeting pipeline developers, environmental regulators and elected officials demonstrate the sustained backlash along routes traversing thousands of miles.

But none of it has been able to stop the explosive growth of gas infrastructure across the region.

The first months of 2018 were marked by pipeline company violations that have impeded the push to construct several high-profile pipelines and fueled doubts that these projects can be built without significant environmental costs.

On Jan. 3, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection suspended construction of Sunoco’s Mariner East 2 pipeline, citing “egregious and willful” violations and a lack compliance with state laws. The order came after Sunoco failed to notify state regulators when drilling fluids used to bore tunnels spilled, even though chemical-laden mud has impacted waterways and private drinking water wells in 10 of 12 counties along the pipeline route.

The suspension was lifted a month later after Sunoco paid a $12.6 million fine. But on March 16, Mariner East 2 incurred another violation — its 40th since May 2017 — for releasing 50 gallons of drilling fluid into a stream in Lebanon County. The 350-mile pipeline would transport natural gas liquids across southern Pennsylvania.

On March 5, West Virginia regulators halted construction of the Rover Pipeline, a 713-mile project being developed by Energy Transfer Partners that stretches from West Virginia to central Michigan. Officials cited the company for more than a dozen water pollution violations in three northern counties for, among other things, failure to control erosion and to immediately report non-compliance.

On March 27, advocates called for Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam to halt pipeline tree-clearing and to ensure that the state reviews individual stream crossings. Photo by Cat McCue

Considering the frequency and severity of permit violations slapped on the new spate of pipelines, opponents wonder if state agencies have the resources to effectively monitor construction activities as more projects prepare to break ground.

“We’re seeing the [West Virginia] DEP enforcement staff is very busy with this one pipeline, but what happens when we layer three or four pipelines at the same time, as far as keeping an eye on things?” Angie Rosser, executive director of West Virginia Rivers Coalition, asked in the Charleston Gazette-Mail.

As the Rover Pipeline nears completion, crews are cutting down trees in West Virginia, Virginia and North Carolina to clear paths for the Mountain Valley and Atlantic Coast pipelines. The companies behind the projects have pledged for years that the pipelines will be built safely and that landowners along the routes will be treated fairly. Yet even during the earliest phases of construction, citizens found reason to doubt those promises.

On March 16, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality issued a notice of violation to the Atlantic Coast Pipeline for clearing trees in 15 spots along restricted zones created to protect water quality. While the state’s order did not stop construction, a spokesperson for Dominion Energy said the company paused tree cutting for three days to “reinforce environmental compliance.”

“We are committed to building this project to the highest environmental standards,” Dominion spokesperson Aaron Ruby said in a statement. “We accept responsibility for falling short of that commitment, and we’ve taken serious steps to prevent it from happening again.”

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline was already pressed for time. A day before the violations were issued, Dominion requested permission from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to continue tree cutting beyond March 31, a deadline intended to protect critical habitat for migratory birds and bats in the three states. But on March 28, FERC denied the company’s request.

Precision Pipeline, LLC, a contractor hired by Mountain Valley Pipeline, has also come under scrutiny for its role in other pipelines plagued by environmental fines and regulatory setbacks. Precision was brought on after what the project’s developers described as an “extensive evaluation and review process” to the Roanoke Times.

Precision Pipeline lists the Rover and Mariner East pipelines on its website as projects it has played a role in developing.

Meanwhile, more gas infrastructure projects are being permitted in the region. After receiving approval from FERC in the final days of 2017, TransCanada has started work on the Mountaineer XPress Pipeline in West Virginia and Gulf XPress compressor stations in Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi. The projects are intended to expand its vast Columbia Gas Transmission network and increase transport capacity from the Appalachian Basin to Gulf states.

The expansive build-out of gas infrastructure in the region is being met with forceful grassroots and legal opposition.

A tree-sit established in February to block Mountain Valley Pipeline tree-felling on Peters Mountain was still running strong in early April. Photo courtesy of Appalachians Against Pipelines

The tree-sitters are stationed in Jefferson National Forest near the site where Mountain Valley Pipeline plans to bore through the mountain directly beneath the Appalachian Trail.

Mountain Valley Pipeline sought a preliminary injunction against the protesters. But on March 20, a West Virginia judge denied the company’s request after developers failed to demonstrate that the tree-sit was within the company’s right-of-way.

One tree-sitter told a reporter with West Virginia Public Broadcasting that she saw the protest as “something that will catalyze the entire community that’s been working together to stop this project and other fossil fuel infrastructure projects within this region.”

Indeed, the action has generated a series of support rallies in Monroe and surrounding counties, including at a gate blocking a U.S. Forest Service road. After the tree-sit began, the agency issued a closure order for a 400-foot corridor of national forest along the pipeline’s route.

Meanwhile, in rural Buckingham County, Va., opponents of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline have established Three Sisters Resistance Camp. The forest camp is hosted by a local landowner who is against the pipeline.

Martha, a camp member who does not want to use her real name for security reasons, says that she and others at the camp have fought the pipeline for several years through other means: lobbying in Richmond, raising awareness and connecting with area residents through hikes and bike rides, and following gubernatorial candidates on the campaign trail. Yet the project is moving forward.

“The landowners are watching the land that they’ve lived on, that their families have lived on for generations, that they planned to retire to — they’re watching the destruction physically in that space,” she says. “And so it feels like the only option we have left at this point is physically putting our bodies in the way.”

Community members have donated food, solar panels and other supplies to the camp, according to Martha.

“This is just the beginning,” she says. “We lost some trees and that’s hard to see, but trees can grow back. I think what we’re really here for is to stop any pipe from going into the ground. So I think in two months we’ll still have that mentality, so we’ll be doing whatever it takes to preserve Virginia.”

As tree felling began in late winter, networks of concerned citizens along the routes of the Mountain Valley and Atlantic Coast pipelines announced plans to carefully monitor pipeline construction and to alert regulatory agencies and the media of any violations.

Along the route of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, organizers of the Pipeline Compliance Initiative, known as Pipeline CSI, expect to partner with hundreds of volunteers in Virginia and West Virginia. The group intends to prepare volunteers for a variety of tasks, including stream monitoring, document review and aerial surveillance. In the case of a spill or other suspected violation, Pipeline CSI would send teams to investigate.

“We strongly believe that the ACP is unneeded and cannot be built safely without causing permanent damage to the environment, particularly critical water resources,” stated Rick Webb of the Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition in a January press release. “We will continue to challenge the government decisions involving the project. But, with certain pre-construction activities already underway, citizen oversight is essential given the limited resources of government agencies that are responsible for regulating pipeline construction.”

At a March vigil in the historic village of Newport, Va., residents who have been fighting the Mountain Valley Pipeline announced the formation of a monitoring program called Mountain Valley Watch.

According to Rick Shingles, coordinator of Preserve Giles County and a program leader, there are a number of reasons why citizen monitoring is necessary, including pipeline builder EQT’s troubling track record and the company’s lack of experience with 42-inch-diameter pipelines or constructing such projects on terrain that is both steep and fragile.

“All that should compel someone to monitor the pipelines,” he says. “Our county governments are not doing it, the only recourse we have is the Department of Environmental Quality, which we don’t feel we can rely on.”

Local organizers are partnering with the Sierra Club and New River Geographics, a Blacksburg-based geographic information systems company, to develop a smartphone app that volunteers can use to send photos and precise locations of suspected violations to what Shingles calls a “central information hub.” From there, once the report is vetted, it would be sent to state environmental regulators and posted online.

According to Shingles, many local citizens are exhausted from the years-long fight against the pipeline. Yet, he says, the idea of Mountain Valley Watch is catching on. “We’re getting a very enthusiastic reaction from people who wish to volunteer,” he says.

“Beside the fact that [monitoring] is truly constructive, there has to be a record of this, of what they did,” Shingles adds.

Editor’s Note, April 13: In the two weeks following our print deadline, the direct resistance to the Mountain Valley Pipeline has grown, as has the response from the U.S. Forest Service and local police. A monopod — a unit rigged atop a pole — with one unnamed individual inside is blocking a forest road on Peters Mountain, and the U.S. Forest Service closed an access road to prevent the monopod sitter from receiving supplies. A 61-year-old woman going by the name Red and her daughter also established a tree-sit on their family orchard in Bent Mountain, Va. On April 13, Roanoke County police announced plans to prevent their supporters from providing the residents with food and water.

Citizens monitoring Mountain Valley Pipeline tree-clearing crews have reported that crews are cutting down trees in violation of the March 31 deadline, and Roanoke County police arrested several pipeline opponents.

EQT Midstream Partners, LP, the developer of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, announced plans on April 11 to extend the pipeline by 70 miles. If built, the extension — called Mountain Valley Southgate — would run from Chatham, Va., to Alamance County, N.C., near Greensboro. As a new project, Mountain Valley Southgate would need to go through federal and state approval processes.

The emergence of independent, citizen monitoring initiatives follows mitigation agreements quietly negotiated between pipeline developers and policymakers in North Carolina and Virginia.

On Jan. 26, the day the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality signed off on the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, Gov. Roy Cooper announced that Dominion and Duke Energy would put $57.8 million into a fund focused on clean energy and rural economic development. Exactly how the money would be spent was not specified.

Republican lawmakers and conservative groups questioned the agreement’s legality and charged Cooper with creating a “slush fund” to support projects he favored. By mid-February, the state’s Republican-led General Assembly had passed legislation diverting the money to public schools along the pipeline’s path.

Cooper let the bill become law without his signature but expressed concern that lawmakers may have jeopardized the deal with Atlantic Coast Pipeline developers by repurposing the fund. As this controversy played out, the existence of a similar agreement in Virginia was soon revealed.

As in North Carolina, the pipeline developers agreed to pay the state of Virginia $57.8 million. The deal, however, is explicit on how the funds would be distributed to mitigate forest and water quality impacts caused by pipeline construction. But unlike the North Carolina agreement, the Virginia arrangement wasn’t made public when it was signed in December, causing suspicion among pipeline opponents.

“When the public got wind of this agreement, it sounded like another backroom pipeline deal that the public got left out of,” Greg Buppert, an attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, told the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “That problem can be fixed if there’s more transparency about what’s going on.”

Landowners and conservation groups including Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper, are also continuing to challenge the approval of various pipeline permits in court.

In March, the Southern Environmental Law Center filed a motion with the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals requesting that the court halt work on the Atlantic Coast Pipeline while it considers another case that the law center has filed challenging the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s approval of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. But the court dismissed the case because FERC issued a “tolling order” that gives the agency more time to reconsider their approval of the pipeline and prevents legal challenges from moving forward in the meantime.

The Southern Environmental Law Center is also challenging Atlantic Coast Pipeline permits granted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service and the Virginia State Water Control Board.

Likewise, legal challenges are underway against the Mountain Valley Pipeline. The nonprofit legal group Appalachian Mountain Advocates is representing a coalition of organizations, including Appalachian Voices, in challenging a permit issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Another legal filing argues the Virginia State Water Control Board and Virginia Department of Environmental Quality should not have granted pipeline companies a certificate under the Clean Water Act.

Hundreds of landowners along the pipeline routes have also gone to court to fight the developers’ claims of eminent domain. While most outcomes have favored the pipeline companies, in March a U.S. district court judge ruled in favor of two North Carolina landowners. The judge found that the Atlantic Coast Pipeline must negotiate with and pay the rural residents before it can begin work on their land.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests