Bill Could Boost Funding to Reclaim Abandoned Mines

By Molly Moore

In Mingo County, W.Va., efforts are underway to restore five acres of former mine land in order to raise fish and grow produce in an aquaponics facility powered by solar panels and geothermal energy from a nearby abandoned underground mine. In addition to providing healthy food, the project also intends to deliver workforce training to the area.

Several hundred miles away in Washington, D.C., lawmakers and officials are faced with policy decisions that could either help create more projects like this or prolong the delayed cleanup of abandoned mines.

The funding behind the Mingo County aquaponics effort comes from a pilot program run by the U.S. Office of Mining, Reclamation and Enforcement that helps states saddled with abandoned mine lands repurpose these places for projects that could benefit the economy and local communities.

The pilot program was first authorized by Congress in December 2015, and the budget deal negotiated this spring expanded its reach.

In 2016, the program provided $30 million each to Kentucky, Pennsylvania and West Virginia — the Appalachian states with the most high priority abandoned mine sites. The spending bill passed in April added Alabama, Ohio and Virginia to the list, and adjusted the funding figures for 2017 to $25 million each for the original three states and $10 million each for the new states.

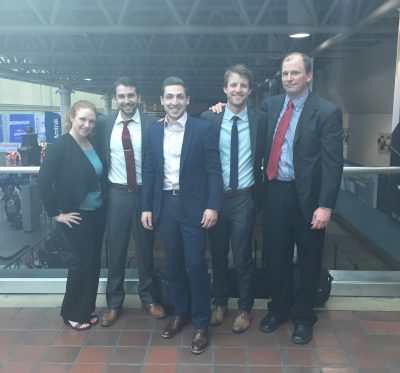

Community advocates from Appalachia and beyond attended the April RECLAIM Act hearing in Washington, D.C.

Left to right: Sarah Bowling of Kentuckians For The Commonwealth, Eric Dixon of Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center, Thom Kay of Appalachian Voices, Colin Lauderdale of Western Organization of Resource Councils and Fritz Boettner of Downstream Strategies.

The pilot program tests the policies included in the proposed RECLAIM Act, a bill that would take existing money from the Abandoned Mine Lands Fund and put it toward reclaiming sites that can be used for economic and community-oriented projects. The funds can be used across the nation, but particularly in places hit hard by the coal industry’s downturn.

Since 1977, when a federal law that governs coal mining and cleanup was enacted, coal companies have had to pay a fee to the Abandoned Mine Land Fund on every ton of coal mined. That fund then distributes payments to clean up mines abandoned before the passage of the law. Reclamation of these abandoned mines is prioritized based on safety hazards and the types of environmental damages at each site.

But communities affected by the coal industry’s latest bust have increasingly called for accelerated AML cleanup and funding to remediate sites that can be repurposed in ways that help local residents. After 28 local governments and representative bodies across four Appalachian states passed resolutions of support for the concept, the RECLAIM Act was first introduced by Kentucky Rep. Hal Rogers in 2016.

As of this spring, the bill is again in play in the new Congress. Rep. Rogers and Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky have introduced a version of the bill in their respective chambers, and West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin reintroduced the original version in the Senate.

“The RECLAIM Act will build on the momentum generated by the pilot and make countless new job-creating projects a reality,” Rogers said during a House subcommittee hearing held on the RECLAIM Act in April. “This bill represents a real investment in coal country – one that will provide much needed resources to clean up the environment, create jobs and strengthen these communities from the ground up.”

But while the version introduced by Rogers and McConnell — H.R. 1731 — would still accelerate the restoration of abandoned mines, the current text includes a few key differences from the original.

During the April hearing, Fritz Boettner of the environmental consulting firm Downstream Strategies testified that, “H.R. 1731 as written does not sufficiently promote the second stated goal of the RECLAIM Act: spurring economic diversification on reclaimed sites.”

That’s because H.R. 1731 specifies that only sites ranked Priority 3 would need to meet the bill’s criteria regarding economic development. According to Boettner, Priority 3 sites, which pose an environmental risk but no direct threat to humans, comprise roughly a quarter of the national unreclaimed mines by cost.

H.R. 1731 also no longer incentivizes states to involve community stakeholders in shaping projects on Priority 1 and 2 sites, which the original RECLAIM Act did. Those Priority 1 and 2 sites pose environmental or safety hazards that can threaten human health.

The AML pilot program, on the other hand, requires an economic component to all projects and encourages local public engagement.

“At this crucial time in rebuilding our economies, we cannot limit our opportunity for real change,” Boettner told the congressional subcommittee. “The aquaponics project is a prime example of a High Priority AML site that will be reclaimed and the site reused to create long-term jobs. There is significant potential for creating permanent jobs with projects like this one.”

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An excellent summary of the history and importance of RECLAIM !