Fracked-gas Pipelines Would Threaten Homes and Dreams

A Tale of Two Families

By Cat McCue

Jill Averitt and her dog, Cliff, enjoy a moment outdoors. The Atlantic Coast Pipeline would cut through her land, along the hillside just beyond the swing set. Photo by Cat McCue

At the top of Sinking Creek Mountain in western Virginia, where Craig, Giles and Montgomery counties meet, sits a 50-acre parcel of land with views in all directions. To Judy and Steve Hodges, who built their dream home here in 2003, it’s heaven.

“We’re from the ‘70s. Leftover hippies, that sort of thing,” says Judy. “We love it here. We have lovely neighbors.”

But to a Pittsburgh-based company, their land is just one of over 1,000 parcels to survey and whose owners have to be dealt with in order to build what would be the largest-diameter natural gas pipeline ever to cross the central Appalachian mountains.

In June 2014, Mountain Valley Pipeline, LLC, announced plans to run a 301-mile line between West Virginia and Virginia to carry gas from the Marcellus and Utica fracking fields. The project would plow a 125-foot-wide construction zone of clear-cutting and excavation across the two states, and require a permanent 50-foot easement.

The pipeline would bisect the Hodges’ land and come so close to their house that an explosion could damage or entirely destroy it. “From everything I’ve heard, this is a new animal we’re dealing with, these 42-inch, high-pressure pipelines,” Judy says. “We don’t want it.”

Same story, different pipeline

To the east, about 110 miles as the crow flies, live Jill and Richard Averitt, who share a similar story to the Hodges. They found property in rural Nelson County in 2005 and built a home where they are raising two children and plan to grow old. The Averitts had done their research to assess the potential for new highways or other public projects that might disturb their idyllic setting.

They didn’t consider pipelines.

In September 2014, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, LLC, announced plans for a 564-mile line, also 42 inches in diameter, also originating in West Virginia and slicing through Virginia, but continuing into North Carolina. This pipeline would run so close to the Averitts’ home that should it explode, their house would be damaged or destroyed. It would also cross a separate parcel where the couple is planning a resort complex that could employ up to 150 people.

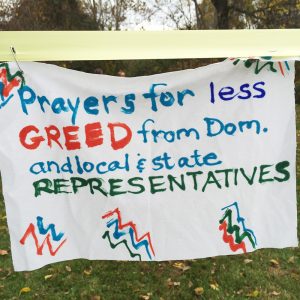

Prayers Not Pipelines

Seeking to demonstrate community solidarity against the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, in fall 2015 Jill Averitt initiated a community art project. White squares of cloth, with colorful, affirming messages written by local residents, line either side of Scenic Route 151 in Nelson County, Va., near the Rockfish Valley Foundation Natural History Center. The display stretches 125 feet on either side of the road — the width of the proposed pipeline.

“Our intention for this is to send out positive messages to the community and the forest. Blessings and protection, if you like. So what is left is not a bunch of ‘No Pipeline’ signs, but prayers going out to the world that this is a protected and sacred place,” she wrote in an email when the project began.

At press time, Averitt was continuing to add new flags with messages from the public.

Since that summer, both families have joined other property owners and climate and clean energy activists (including Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper) to attend public meetings, research the issue, write letters and make phone calls to company and elected officials, hold rallies and stage press conferences.

“It’s been all-consuming,” Jill says. “It’s been incredibly stressful.”

Law against landowners

For Richard Averitt, the most egregious aspect is the 2004 Virginia law that allows natural gas companies to access private property without the landowner’s permission to conduct surveys, even prior to securing federal approval for a project.

“The law transgresses on private property for profit,” he says. “It’s inconsistent with American beliefs. It’s inconceivable this is allowed.”

The Averitts refused to allow pipeline surveyors on their land, and are now being sued by the company, along with about 150 other landowners in Nelson County alone who also refused access to the surveyors. Some landowners, the Averitts included, are fighting back, hiring attorneys to challenge the law’s constitutionality. The cases were unsuccessful in the lower courts and are now on appeal to the Supreme Court of Virginia, says Ben Luckett with the Appalachian Mountain Advocates, a nonprofit organization representing some of the plaintiffs.

The group also challenged a similar law in West Virginia over the Mountain Valley Pipeline. There, however, the statute requires that such projects are in the “public interest,” and because the pipeline was not providing natural gas to local communities, the landowners won. The company has appealed to the West Virginia Supreme Court.

Unlike the Averitts, the Hodges did allow surveyors on their land; they were told they would be responsible for court costs if they sued and lost. “So we pretty much caved at that point and let them on the land,” Judy says.

Several teams of surveyors arrived on different days. One day, the surveyors packed up and left, telling Judy the land was “unbuildable” due to the steep slope, karst geology and multiple sinkholes.

Yet when Mountain Valley Pipeline filed for its federal permit in October, the proposed route still ran smack through the middle of the Hodges’ land.

Forest Service Denies Atlantic Coast Pipeline Route

In January, the U.S. Forest Service announced it had denied a “special use permit” to Atlantic Coast Pipeline, LLC, to cross 50 miles of the Monongahela National Forest in West Virginia and George Washington National Forest in Virginia. The agency declared that the proposed route failed to protect “highly sensitive resources, including Cheat Mountain salamanders, West Virginia northern flying squirrels, Cow Knob salamanders, and red spruce ecosystem restoration areas.” The decision means the company must find an alternate route that does not impact the areas of ecological concern to the forest agency.

Editor’s note: A new route that cuts through Highland, Bath and Augusta counties was proposed on Feb. 12, 2016. Read the response from environmental groups including Appalachian Voices.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

3 responses to “Fracked-gas Pipelines Would Threaten Homes and Dreams”

-

It’s the insurmountable and irrevocable costs of the future leaks that never get factored in because, well, they just won’t leak; until they do, of course.

-

I dont like these pipelines EXCEPT for the fact that the gas is cleaner than COAL & the coal dust that is blown around where it is collected,,,,Cheap gas puts coal plants out of action & destroys the need for coal /mountain top removal.

-

The ACP would have large, negative economic consequences for the people and the communities along its proposed route. We estimate $6.9 to $7.9 billion, in present value terms, for just four counties. (See http://keylogeconomics.com/wp1/projectsandpublications/acpcosts/ for details).

A similar study on the MVP is in the works.

Leave a Comment