Global Connections

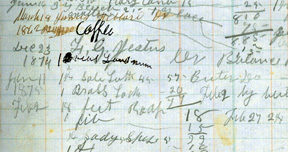

Goods we take for granted today, such as spices, sugar, silk and coffee, were once signs of the early global trade system. This collage of accounts from Valle Crucis, N.C.’s Taylor and Moore Store ledger (1861 to 1874) also includes a line for the opium-based laudanum, a common pain reliever and overall remedy used during the time period; the opium to make this would have likely come from Britian or China. Images courtesy of the W.L. Eury Appalachian Collection, Appalachian State University

By Jamie Goodman

Appalachian history is full of misleading stereotypes and misrepresentations, but none could be more inaccurate than the myth of isolationism.

As far back as the earliest explorers, European immigrants to Appalachia participated in a burgeoning global market. Frontiersmen such as Daniel Boone and Simon Kenton earned their keep hunting and trapping in the wilds of the Appalachian mountains, selling deer, beaver and otter furs to traders who would transport them to port cities such as Baltimore, Md., or Charleston, S.C., and then on to the hands of European citizens who prized the exotic items.

Even in the late 1600s, Native American tribes who interacted with the first foreign explorers quickly grasped that they were interested in New World commodities, and traded pelts for European-made goods. Settlers to the area also saw economic opportunity in the abundant land; greed over these resources was one of the factors that would ultimately force the Native Americans out.

“There is a political sociologist who argues that settlement of the mountains was driven by some sort of capitalist forces,” says Dr. Pat Beaver, director of the Center for Appalachian Studies at Appalachian State University. “We know that the fur trade was a big driver for exploration, and if you go back to the very earliest exploration, it was the quest for gold.”

When pioneers began to settle the mountains, they immediately began farming and wildcrafting native herbs to sell to intermediary traders in exchange for more cultivated overseas goods.

“If you look at old store records from the early 19th century, you’ve got coffee and tea and ginger, nutmeg, silk and china, and those were all part of this international trade,” says Beaver.

Ginseng was among the first wild mountain goods that made it to markets around the world, reaching China by the late 1700s. The prized herb may also be one of the earliest examples of Appalachian resource exploitation. According to the historical tome, “First American Frontier: Transition to Capitalism in Southern Appalachia,” by Wilma Dunaway, merchants from the Virginias “exported ginseng, yellow root, mayapple root, and snakeroot for nearly ten times the value they allowed local customers in barter.”

“One western North Carolina merchant exported 30,000 pounds [in one year],” Dunaway writes. “By 1840, Appalachian Ginseng was becoming scarcer, but the region exported $83,273 worth of the herb in that year — nearly one-fifth of the country’s total supply.”

According to Dr. Beaver, other markets were tied into the flourishing New World economy, including a triangular trade route that brought slaves from Africa and rum from the Caribbean in exchange for Appalachian goods.

The Extraction Revolution

Almost from the time pioneers started exploring the Appalachian mountain range, minerals were being extracted from the vaulted hillsides. Dunaway writes that saltpeter (used to produce gunpowder), alum (used for canning), salt from West Virginia, manganese from Southern Appalachia, lead from southwestern Virginia, gold from Georgia and Tennessee, and copper from Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia were all part of the initial rush to mine underground mountain resources for profit. Even Appalachian mineral water was bottled and exported to distant markets.

By the early- to mid-1800s, coal was already established as a key commodity in both domestic and international trading. According to Dunaway, in the 1840s close to three-quarters of a million tons of Maryland coal were being exported to Cuba and France. By 1860, “four-fifths of the region’s coal was being sent to regional, midwestern, and southern markets” to power foundries, fuel salt manufacturing, and propel steamships on the fledgling country’s mighty rivers.

But it was the advent of the railways that truly established Appalachia’s role in modern world trade. “I’d say that period of 1880s to 1920s is a real big, radical change in terms of [timber and coal],” says Beaver. “By the 1880s, things were really moving.”

According to “First American Frontier,” timber exports to places such as Western Europe and the West Indies swelled in the mid-19th century because “they had already cut their own timber.” Dunaway writes that “From the Clinch Valley of upper East Tennessee and southwestern Virginia, 1,000 rafts per year headed south for reexport out of Knoxville and Chattanooga.”

Massive logging took place throughout the southern Appalachians, with one company from Maine heavily lumbering as far south as the north Georgia mountains and exporting the timber through Savannah, helping to establish it as a major port city.

Following the railroad revolution, a new commodity was being imported into the region. Coal miners from Wales arrived in Appalachia, followed by Irish, Polish, Czechs and Greeks, among others, all looking for work and a new beginning in the region’s coal mines.

“[You had] political upheaval or drought or famines or wars driving out migration from Europe, and then the opportunities and the lures of expanding markets and industries [were] bringing people in,” says Beaver. “They’re the same kind of drivers that are happening now. People are following the industries and the industries are going where labor is inexpensive.”

Flash Forward

In this issue of The Appalachian Voice, we take a look at globalization as it has evolved to the present, and how Appalachia fits into — and influences — the international community. Through the bluegrass music revolution of the 1970s and the Latino migration of the 1990s, to the furniture crash of the 2000s, the rebirth of small farms following the demise of the tobacco industry and the rise of community activism in the face of mining issues, the seemingly microcosmic culture of Appalachia continues to have a larger-than-life presence in the world.

Recently, scholars, activists and artists from more than 60 countries — including Ecuador, Wales, India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Mali, China, Italy, Canada, Mexico and the U.S. — gathered at a three-day Global Mountain Regions conference at the University of Kentucky to talk about their shared experience of living in mountain communities that have struggled with resource extraction and other exploitation as part of the modern global market.

“For the future well-being of Appalachian communities, I think it will be very important to be in conversations with mountain communities around the world,” says Dr. Ann Kingsolver, co-organizer of the event and director of the university’s Appalachian Center and Appalachian Studies program. “I think the exchange is vital as we go forward.”

Related Articles

Latest News

More Stories

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

![“[There are] still a lot of individuals who need support, especially here in Green Cove, Whitetop, Konnarock — those are the communities up on the mountain,” says Little. “We were a part of Damascus, but because we are on the mountain outside of Damascus, a lot of the resources and help have not made their way here.” Photo by Jimmy Davidson.](https://appvoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Virginia_Creeper_Trail_JMDavidson-32-1024x768.jpg)