What’s Coming Down the Natural Gas Pipeline?

The race to replace coal with natural gas

Citizen opposition to the proposed pipelines is well-organized and far-reaching. In August 2015, groups from across the region joined in solidarity to take a stand to protect their communities. Photo courtesy of Yogaville Satchidananda Ashram

By Elizabeth E. Payne

Fracked from the Marcellus and Utica Shale formations beneath Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio and West Virginia, a surplus of natural gas is now poised to surge into Virginia and North Carolina, bringing with it promises of a cheaper, “greener” future supported by a new and improved energy infrastructure.

But many citizens and economic experts are raising questions about just how “green” a fossil fuel can really be and how steep a toll — both financially and environmentally — its infrastructure will take.

As of 2008, the United States was criss-crossed by more than 305,000 miles of natural gas pipelines, and since then this figure has risen steadily. In central and southern Appalachia, a web of pipelines invades the landscape, linking the drilling wells from shale country to state and regional pipelines, storage facilities, power plants and coastal ports for export.

Natural Gas Infrastructure Webinar

May 3, 2-3 p.m: Appalachian Voices will host a panel discussion about the environmental,

financial and personal costs of the proposed pipeline projects. Free.

Visit appvoices.org/webinars

Prominent among these is the Transcontinental Pipeline, operated by Williams Companies. The Transco line extends more than 10,000 miles and stretches from south Texas to New York City.

But plans, sponsored by energy companies such as Dominion Resources and Duke Energy, are underway to stretch even more pipelines across the region. These pipelines would connect the Marcellus gas to new transport facilities and power plants in a web as intricate as that connecting the subsidiaries of the companies themselves.

Several proposed projects will extend and upgrade existing routes. Columbia Pipeline Group’s $850 million WB XPress Project will add two new compressor stations, replace 26 miles of existing pipeline and add 2.9 miles of new line in Virginia and West Virginia. In March 2014, Williams announced a $2.1 billion plan to expand the capacity of the Transco line and change the direction of the flow to carry Marcellus gas to customers in the Southeast and eventually to the Gulf Coast for export.

But in the last two years, two major new pipeline plans have been submitted to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for approval. FERC, the federal agency that regulates the transmission of electricity, natural gas and oil, is responsible for evaluating and approving new pipeline proposals.

The first is the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, a $5.1 billion project by Dominion, Duke Energy, Piedmont Natural Gas and AGL Resources, which would construct a 564-mile pipeline stretching from West Virginia into Virginia and North Carolina. In January, the U.S. Forest Service rejected a portion of the route proposed to run through the Monongahela and George Washington National Forests out of concern for endangered species that reside there. A rerouted path was announced in February and continues through the regulatory process.

The second is the Mountain Valley Pipeline, a $3.5 billion joint venture headed by EQT Midstream Partners, which plans to lay 301 miles of pipeline from West Virginia into Virginia.

Additionally, Williams is considering an Appalachian Connector Project, which would also construct a new pipeline from West Virginia into Virginia. No proposed route or cost for this project has been announced.

Environmental Impacts

Citizens living along the routes of the proposed pipelines are worried about the risks, such as the damage caused by an explosion along the Transco line in 2008, near Appomattox, Va. Photo courtesy of Allegheny Blue-Ridge Alliance

In 2015, the Obama administration announced the Clean Power Plan to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere by the nation’s coal-fired power plants.

Ironically, this act that was designed in part to reduce the effects of climate change, is being used as justification for the switch to natural gas. The plan limits carbon dioxide emissions — the largest source of domestic heat-trapping greenhouse gases and a significant byproduct of burning coal for electricity — but it does not govern methane, the second largest source of greenhouse gases and a significant byproduct of natural gas extraction and combustion.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the negative impact of methane on climate change is more than 25 times greater than that of carbon dioxide.

According to Glen Besa, director of the Virginia chapter of the Sierra Club, a report the organization released earlier this year found “that greenhouse gas pollution from the Atlantic Coast and Mountain Valley pipelines would be almost twice the total climate-changing emissions from existing power plants and other stationary sources in Virginia.”

And according to the Natural Resources Defense Council, the potential environmental hazards linked to natural gas are significant and include air, water and noise pollution; methane leaks and explosions; and human-induced earthquakes.

Citizen Action

Concerned by this looming threat, residents in counties along the proposed routes have organized in opposition to the new construction project in groups such as Friends of Augusta, Preserve Monroe and Yogaville Environmental Solutions. Other groups, such as the Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance, form coalitions between organizations. Still others, such as Appalachian Mountain Advocates, Appalachian Voices, the publisher of The Appalachian Voice, and the Southern Environmental Law Center advocate and litigate on their behalf.

Through this network, concerned citizens of the region are educating themselves and their neighbors about the risks of the pipelines and are working together to oppose them.

This construction corridor is wide enough to accommodate a 12-inch pipe adjacent to a 6-inch pipe. The corridor for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and Mountain Valley Pipeline will be much wider in order to fit pipes 42-inches in diameter. Photo courtesy of Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition

Roberta “Bert” Bondurant lives in Roanoke County, Va., along the proposed route of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. She is a member of Preserve Roanoke and serves on the county’s Pipeline Advisory Committee.

One of her many concerns is the effect the pipeline’s construction — with its blasting and clear-cutting across steep mountain slopes and wetlands — would have on the county’s drinking water through erosion and disruption of streams and rivers. “MVP proposes to do a clear-cut, a cross cut, which is the simplest and crudest form of construction across Roanoke River, down on the southwest side of Poor Mountain about a mile and a tenth upstream of Roanoke County’s reservoir,” Bondurant says. “Roanoke County pumps water from the Roanoke River into its reservoir, and so what you’re talking about is that this is upwards of 50 percent of Roanoke County’s drinking water.”

Charlene “Chad” Oba is co-chair of Friends of Buckingham, a citizen group opposing the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. One of Oba’s main concerns is the impact a proposed compressor station would have on her health and quality of life and that of her neighbors.

Compressor stations are positioned at intervals along a pipeline to pressurize the natural gas and provide energy to transmit the gas. According to the Roanoke Times, Dominion Transmission Inc. — senior partner in Atlantic Coast Pipeline LLC — purchased 65 acres of land in August 2015 for $2.5 million. The parcel is near the intersection of the Transco line and proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline and would allow a connection between the two.

Oba is concerned about the air and noise pollution from the compressor. She describes the neighborhood where the compressor would go as largely older and African-American. “They’re a lot of elderly people, a lot of people who already have bad health,” she says. “So, there are a lot of vulnerable people that are greatly at risk.”

Some area residents are in court for refusing to give Dominion permission to survey their land. Appalachian Mountain Advocates is representing some of these landowners, and is currently appealing the company’s right to survey private land without eminent domain before the Supreme Court of Virginia.

“The taking of private property for corporate profit is wrong,” Oba says. “It puts our health at risk. It puts our property value at risk.”

Vicki Wheaton lives in Nelson County along the proposed route of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and wants to stop the pipeline’s construction. Wheaton is an active member of Friends of Nelson County. She is encouraging the county to adopt higher floodplain standards regarding critical infrastructure and hazardous materials because they meet the federal requirements.

If adopted and enforced, these higher standards could be used by the county to block the construction of new infrastructure, such as the pipelines. “These higher standards would protect Nelson County residents,” she wrote in an email.

Economic Impacts

In February, a team from Key-Log Economics LLC presented the findings of a study commissioned by five citizen groups representing four counties along the route of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, including Friends of Nelson County and Friends of Buckingham, Virginia.

Spencer Philips, an ecological economist and principal at Key-Log, co-authored the study “Economic Costs of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline,” which is designed to serve as an model for the type of analysis FERC should undertake before signing off on either of the pipelines. In the study, Phillips and his team found that residents would carry a tremendous cost burden, including loss of property value, estimated at between $72.7 and $141.2 million, and annual costs, such as the resulting lost property tax revenue and ecotourism, estimated at between $96.0 and $109.1 million per year.

Following the Money

Thomas Hadwin, a resident of Waynesboro, Va., is a member of Friends of the Central Shenandoah who spent many years working in the electric and gas utility business in Michigan and New York state. He is skeptical of the need for more pipelines and sees far more promise in energy efficiency efforts. “By far the cheapest way of getting more electricity is to not use it at all,” he says.

For Hadwin, the development of the Marcellus Shale began with profit-seekers and easy credit following the collapse of the housing market in 2007 and 2008. “All these drillers are in there chasing this high price for natural gas with cheap money,” he says.

But then the price for natural gas fell dramatically, in part due to oversupply, and the economics changed.

For the second quarter of 2015, the Houston Chronicle reports that “U.S. shale drillers now spend the vast majority of their operation cash flow paying off the debt they took out to expand their drilling.” According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, that figure is 83 percent.

“More gas is being produced because these guys [the drillers] couldn’t afford not to produce it,” Hadwin says. “They’ve got all this cheap debt, but they have to pay the interest on it, they have to keep servicing the debt.” This adds to the surplus and continues to deflate the cost of the gas.

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis is preparing a study of the “finances of the Atlantic Coast and Mountain Valley pipelines in the context of the larger buildout of pipeline infrastructure from the Marcellus and Utica region,” Cathy Kunkel, energy analyst for the institute, wrote in an email.

The study, co-authored by Kunkel and Director of Finance Tom Sanzillo, will investigate whether too many pipelines are being built, how they are being paid for and whether FERC’s review process is effective at preventing pipeline overbuilding.

The study is expected in late April and was commissioned in part by Appalachian Voices.

Unnecessary Expansion

In a report released in February, the U.S. Department of Energy concluded that pipeline capacity added since 2007 to accommodate increased shale production is “likely to reduce the need for future pipeline infrastructure” and that “higher utilization of existing interstate natural gas pipeline infrastructure will reduce the need for new pipelines.”

In other words, the department doesn’t forecast a need for significant pipeline expansions of the sort being proposed. And a study out of University of Texas at Austin predicts that the four main accumulations of gas beneath the Marcellus Shale could peak as early as 2020 and then begin to decline.

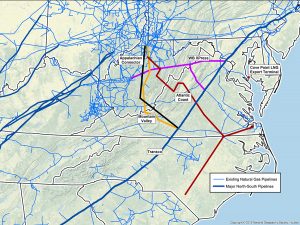

Click to enlarge the map. Central and southern Appalachia are covered by a network of existing pipelines, shown above in blue lines. Plans are underway to add several major pipelines to this web, shown in different colored lines. Not shown are the compressor stations and power plants across the region. Map by Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition

Yet in September 2014, Dominion announced a $3.8 billion plan to convert the Cove Point LNG Terminal in Maryland, which was originally built in the 1970s as an import facility, to an export facility. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, it is the only approved natural gas export facility on the East Coast. And it “is connected to Dominion Transmission’s interstate pipeline, as well as to other interstate pipelines that have access to the growing natural gas supplies in the region,” according to the company’s description.

Power plants are also being adapted, based on the expectation of cheap natural gas. Duke Energy’s Western Carolinas Modernization plan, for example, that will cost nearly $1 billion and will require “two 280-megawatt natural gas-fired combined-cycle power plants [that] will be located at the current Asheville coal plant site.”

Citizen and environmental groups have fought successfully to reduce the scale of this project. But if it goes forward, it may be redundant from day one. In February, officials from Columbia Energy told the Citizen-Times that they could sell Duke Energy electricity from their existing natural gas power station in Gaston, S.C. They can supply enough to make the Asheville plants unnecessary.

Moving forward

A study released by the Union of Concerned Scientists in March 2015 describes a place for natural gas in the nation’s energy future but warns against an over-reliance on gas. “As the nation moves away from coal, setting course toward a diverse supply of low-carbon power sources — made up primarily of renewable energy and energy efficiency with a balanced role for natural gas — is far preferable to a wholesale switch to natural gas,” the study reported.

Expanded energy efficiency and renewable energy policies would be in the best interest of consumers. But according to one of their applications to FERC, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline partners anticipate a sizable profit from this construction project — in financial jargon, they foresee a 15 percent pretax return on their investment. “So, they’re getting a huge rate of return in today’s marketplace,” Hadwin says.

And with profits like that, it would be hard for these investors to walk away.

CORRECTION: The print version of this article incorrectly stated that Charlene “Chad” Oba had refused pipeline surveyors from Dominion access to her land. Oba’s land is not in the path of the pipelines, however other landowners have refused entry to surveyors and are facing a legal challenge from Dominion. Appalachian Mountain Advocates is appealing the case before the Supreme Court of Virginia. The article has been corrected accordingly.

Related Articles

Latest News

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

2 responses to “What’s Coming Down the Natural Gas Pipeline?”

-

Domestic natural gas cannot be presumed for “export only.” How about domestic consumption? For instance, natural gas Big Trucks? They’re already a staple in Canada.

Additionally, natural gas power plants consume by some estimates 175 million cubic feet per day to power 1 million homes(I’m quoting here).

Switching fuels for these two industries will necessitate more pipelines. “For export only”, your main premise, cannot be confirmed.

-

Well done with summarizing a great deal of scientific and also front-line community issues about multiple sorts of negative impacts of fracked gas. These communities are the places proposed to carry the burden for the U.S. and mostly foreign markets of [not[ “clean energy” produced by fracked gas from its injection wells production sites along pipeline routes propelled at 53,000hp turbine engine compressor station industrial complexes. No surprise these injection wells and the compressor station proposed for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) are in rural, low-income counties eager for corporate tax revenues or lease royalties used as incentives to exchange presently pure ambient air, water, and soil quality for highly toxic routine emissions of methane, Co2e, formaldehyde and more. In general, as Ms. Payne reports, royalties and taxes have been much lower than promised in PR campaigns by the gas industry or almost negligible after all the deductions for their construction and production costs and huge drop in gas prices.

Leave a Comment